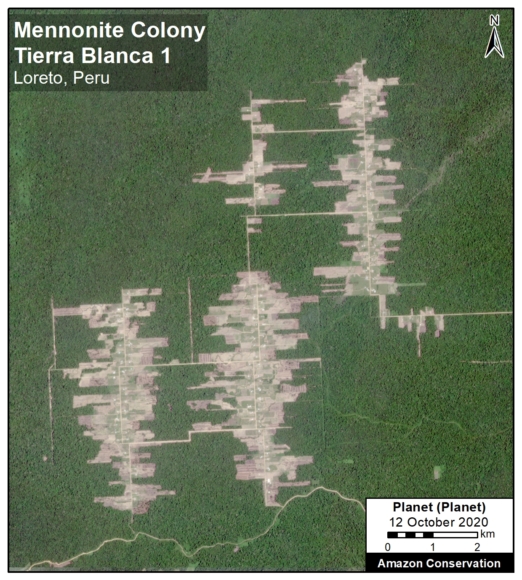

Here, we confirm the massive deforestation of primary forest (more than 2,000 hectares) in the Peruvian Amazon by the company United Cacao between 2013 and 2016.

We present a series of recently obtained (and never before published) satellite images to emphasize the reality and importance of a deforestation case that is still being debated at the highest levels in the Peruvian government, seven years later.

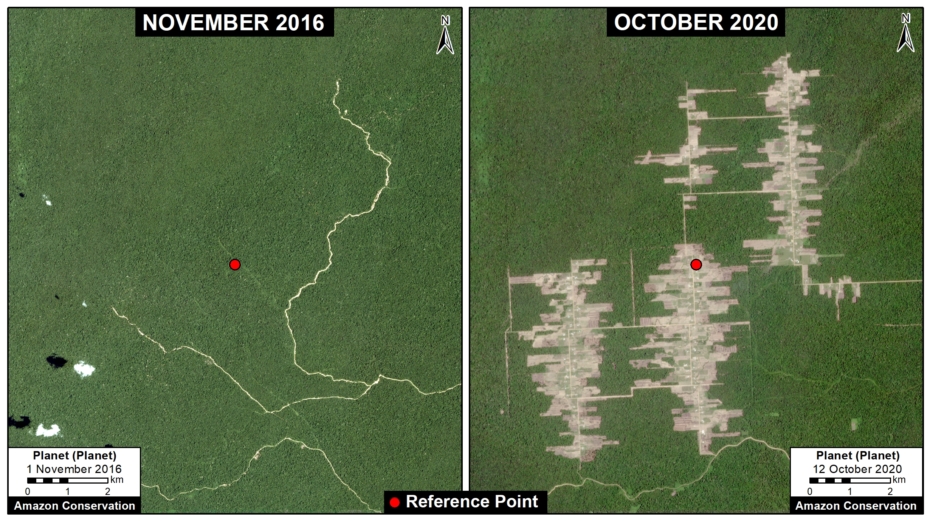

In June 2013, a high-resolution satellite, through scattered clouds, revealed the start of massive deforestation of primary forest near the town of Tamshiyacu, in the Loreto region (Image 1).

In August of that same year, the clouds cleared a bit more, giving a better view. Image 2 (see below) shows the rapid deforestation of primary forest in 2013.

By September 2015, the deforestation had reached 2,380 hectares, or 5,880 acres (Image 3).

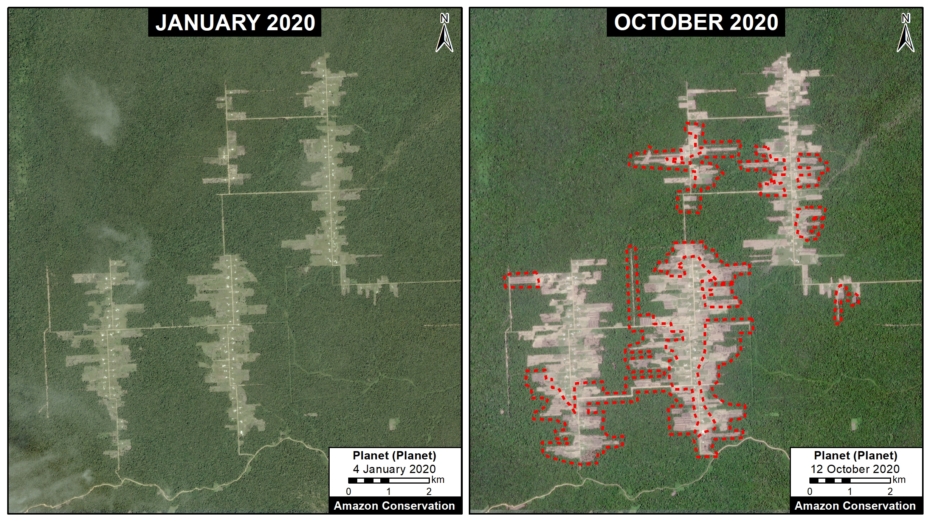

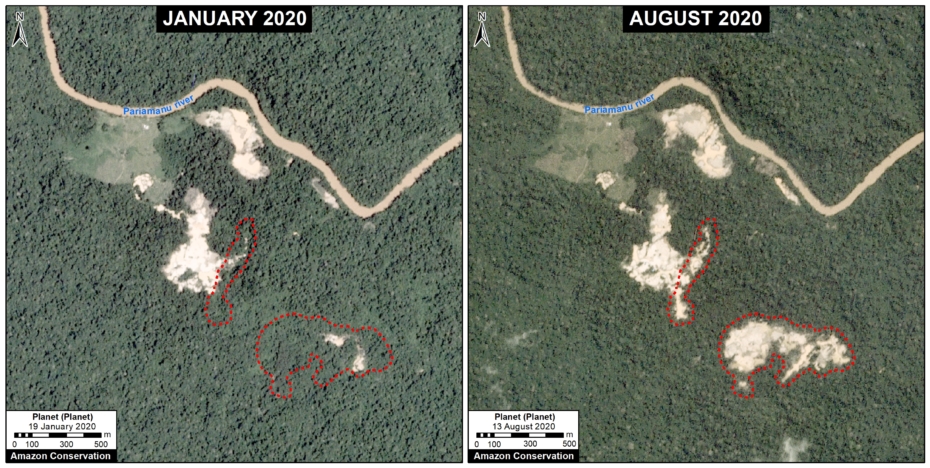

Most recently, in October 2020, a new very high-resolution image shows cacao crops in areas that, seven years ago, were primary forest (Image 4).

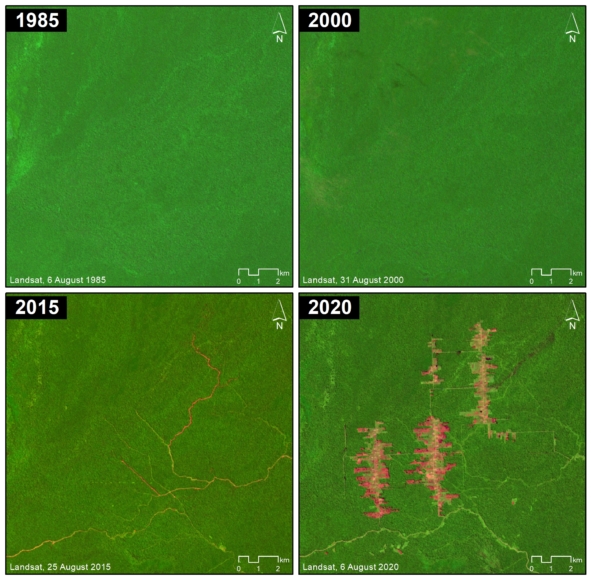

Below, we show, for the first time, these high and very-high resolution images (5 and 0.5 meters, respectively) recently obtained from the satellite company Planet, clearly showing the situation from 2012 -2020. Additionally, we show the historical context with Landsat images dating back to 1985, and briefly describe the current political situation regarding the case.

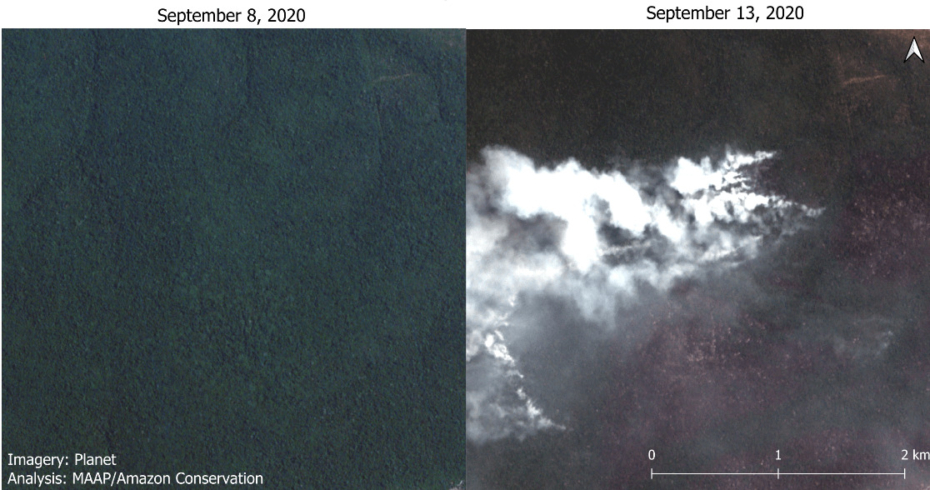

Deforestation 2013

Image 2 shows the first stage of large-scale deforestation (1,100 hectares) by the company United Cacao, between August 2012 (left panel) and August 2013 (right panel).

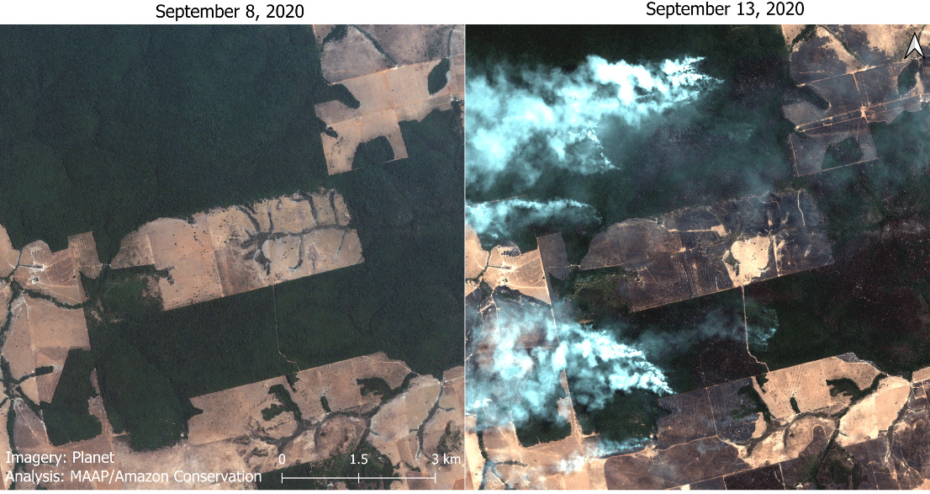

Deforestation 2015

Image 3 shows the total large-scale deforestation (2,380 hectares, or 5,880 acres) by United Cacao between August 2012 (left panel) and September 2015 (right panel). Insets A-C indicate the locations of the zooms below.

2020 – Cacao Crops in Deforested Areas

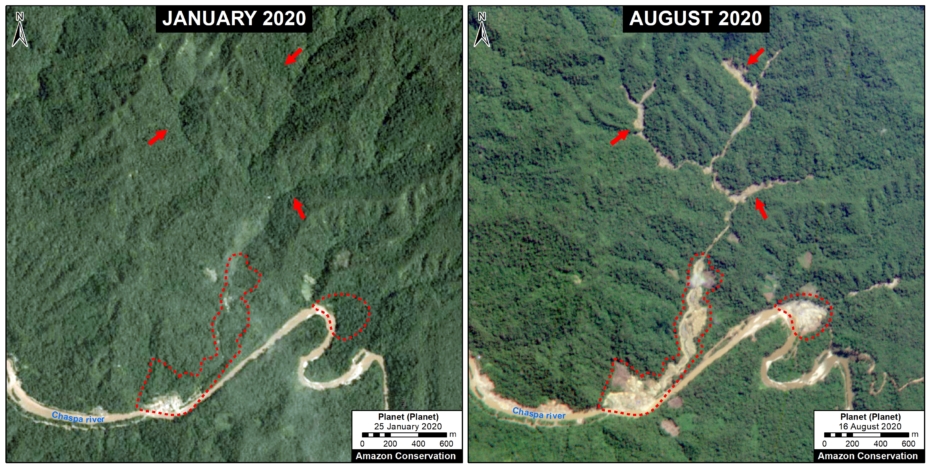

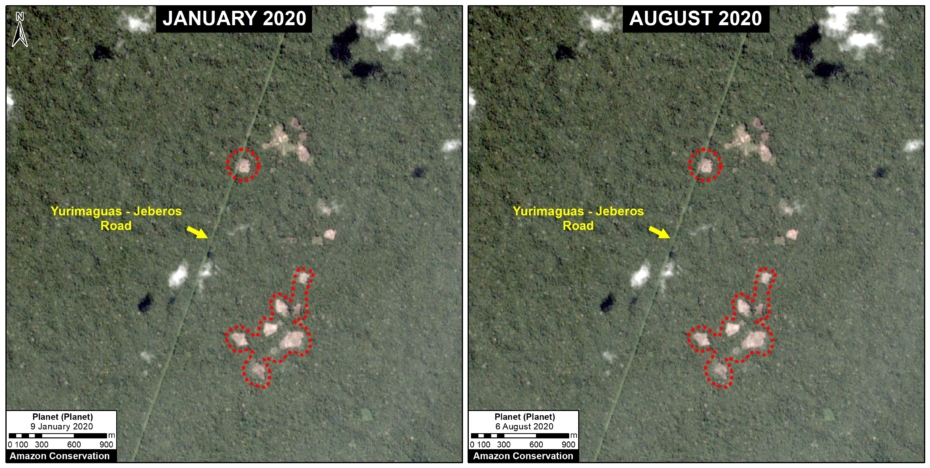

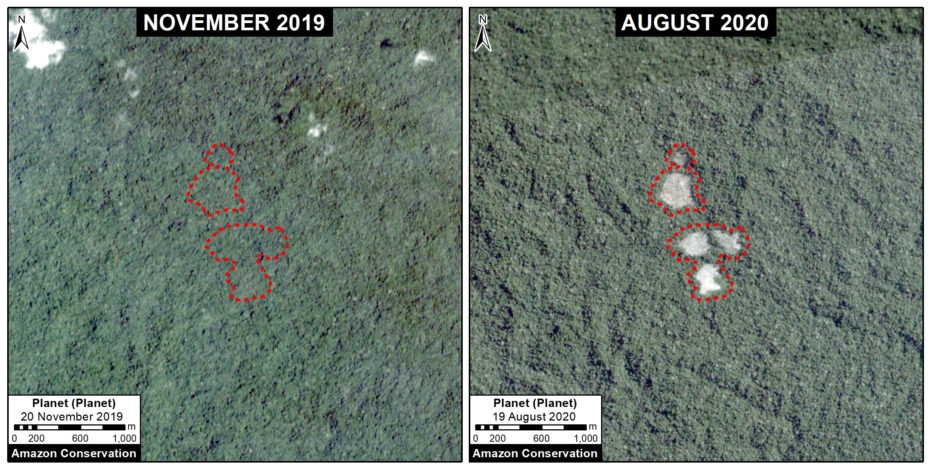

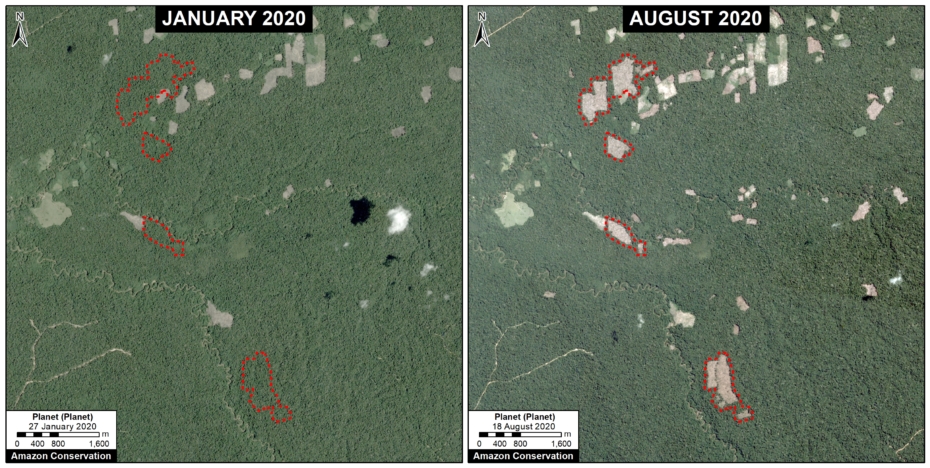

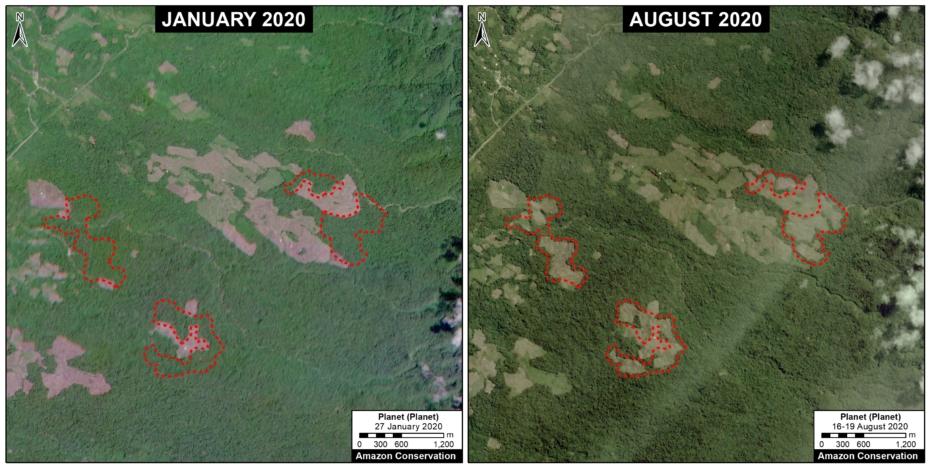

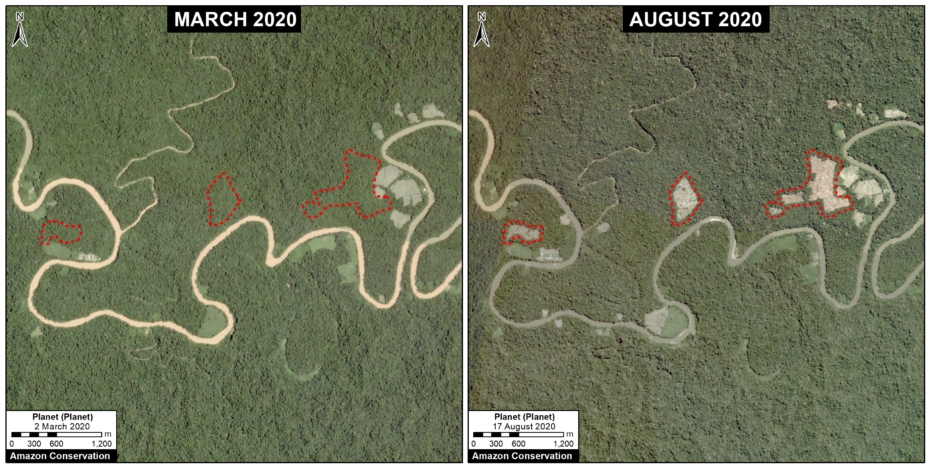

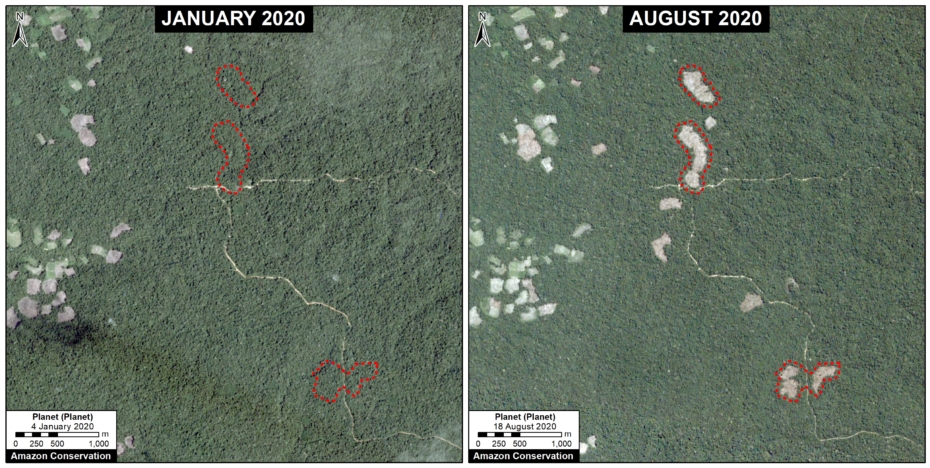

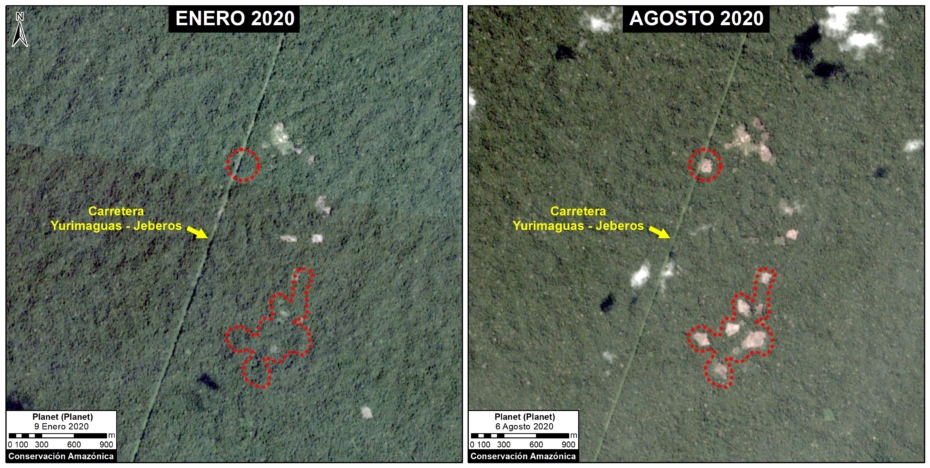

Images 4-6 show current cacao crops (right panel) in areas that, seven years ago, were primary forest (left panel).

Current Policy Situation

In 2014, the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) ordered United Cacao (Cacao del Perú Norte SAC) to halt its development and production activities, but the company did not comply.

In 2019, MINAGRI rejection the Program for Adequacy and Environmental Management (PAMA) presented by the company that took over the operation, Tamshi S.A.C. The PAMA is a type of environmental impact evaluation for projects already in operation.

Also in 2019, environmental enforcement of the case was transferred from MINAGRI to the Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement (OEFA).

Most recently, OEFA issued a major fine, equivalent to around $35 million, to the company Tamshi S.A.C. for carrying out activities without having an approved environmental management plan. OEFA also issued 17 corrective measures, one of which was the immediate stoppage of activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Ipenza, A. Felix, C. Noriega, S. Novoa, and G. Palacios for their helpful comments on this report.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This publication is made possible with the support of the American people through USAID. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

This work was also supported by NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation), and ICFC (International Conservation Fund of Canada), and EROL Foundation.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) United Cacao Case – 7 Years After Massive Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 128.