Mining News Watch #18 covers the time period July 31st- October 31, 2015

Top Stories

-

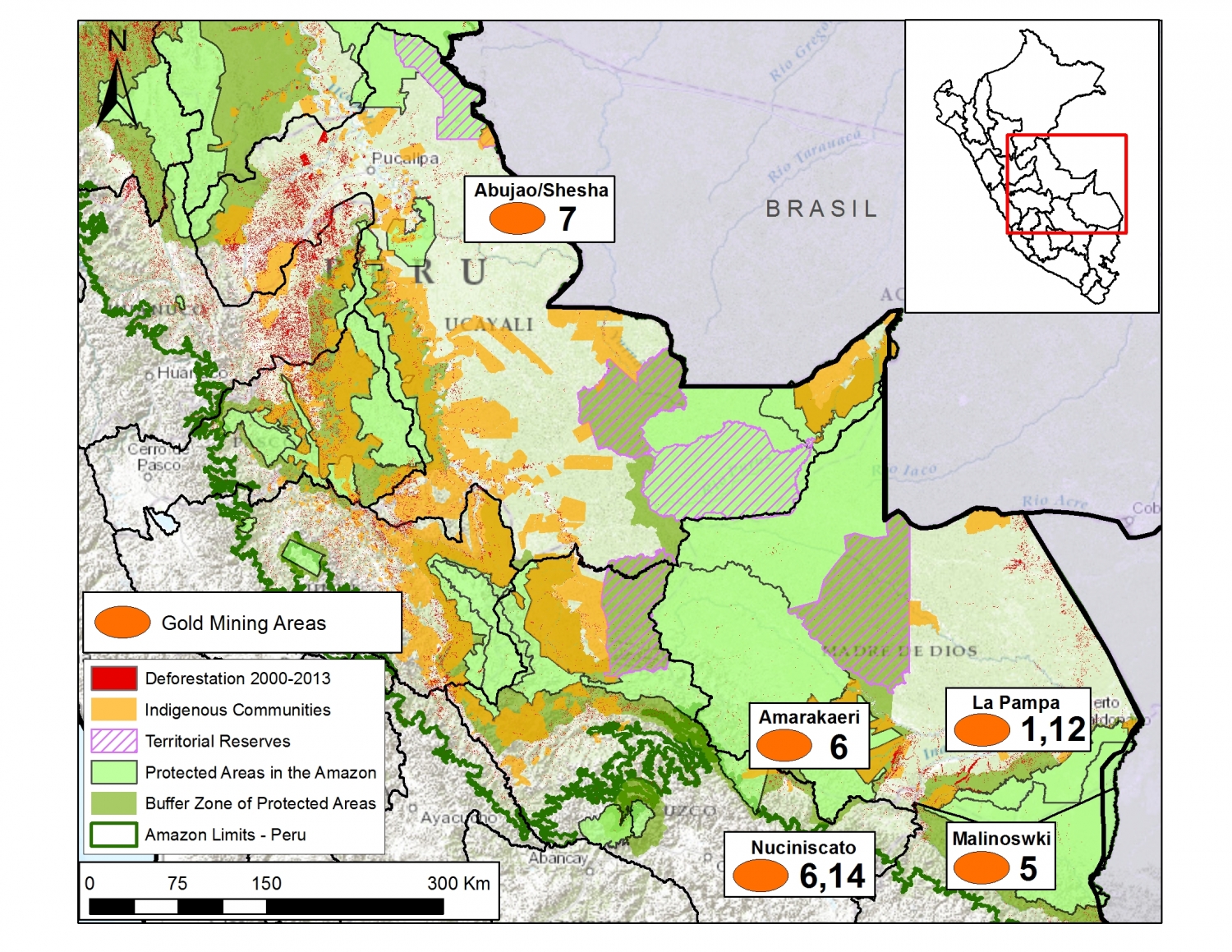

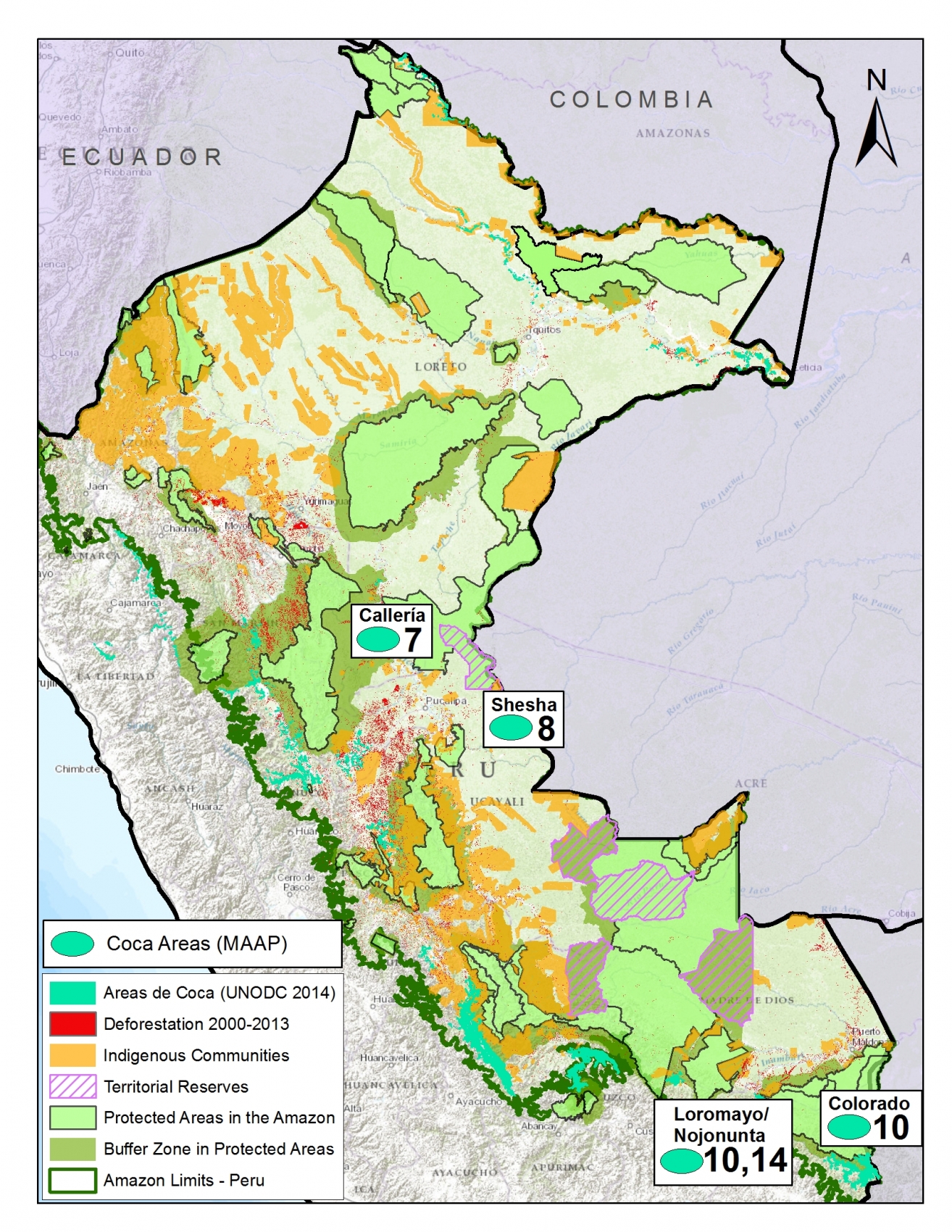

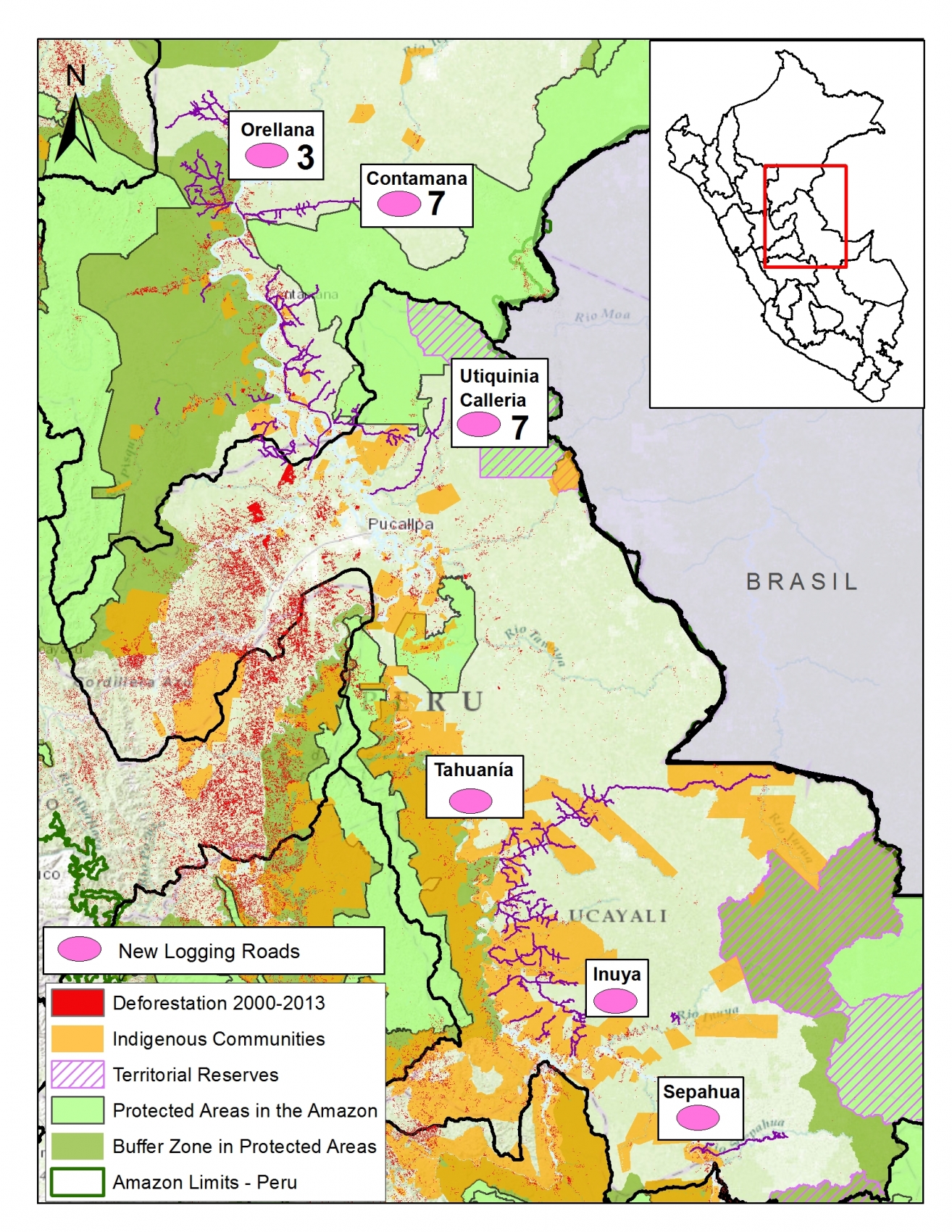

There have been three police raids in Madre de Dios this summer in an attempt to stop illegal gold mining in the region.

-

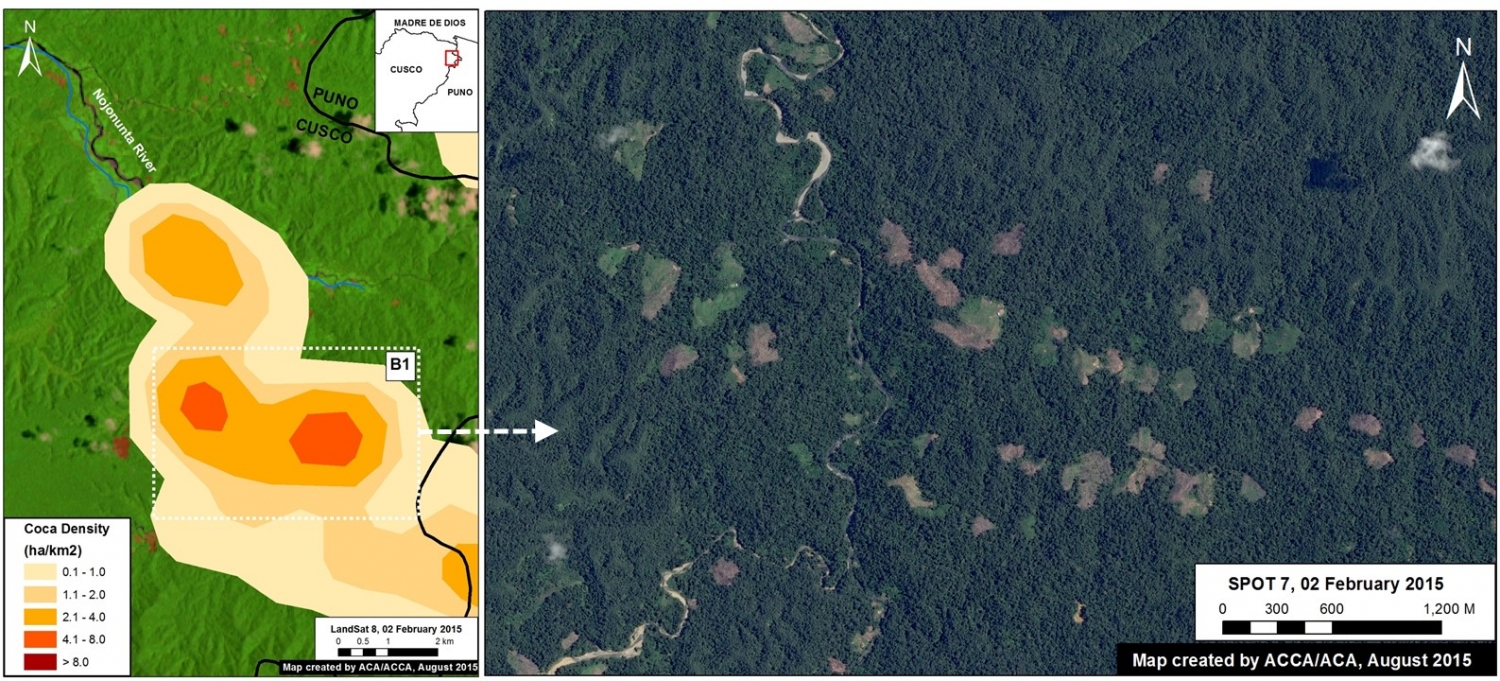

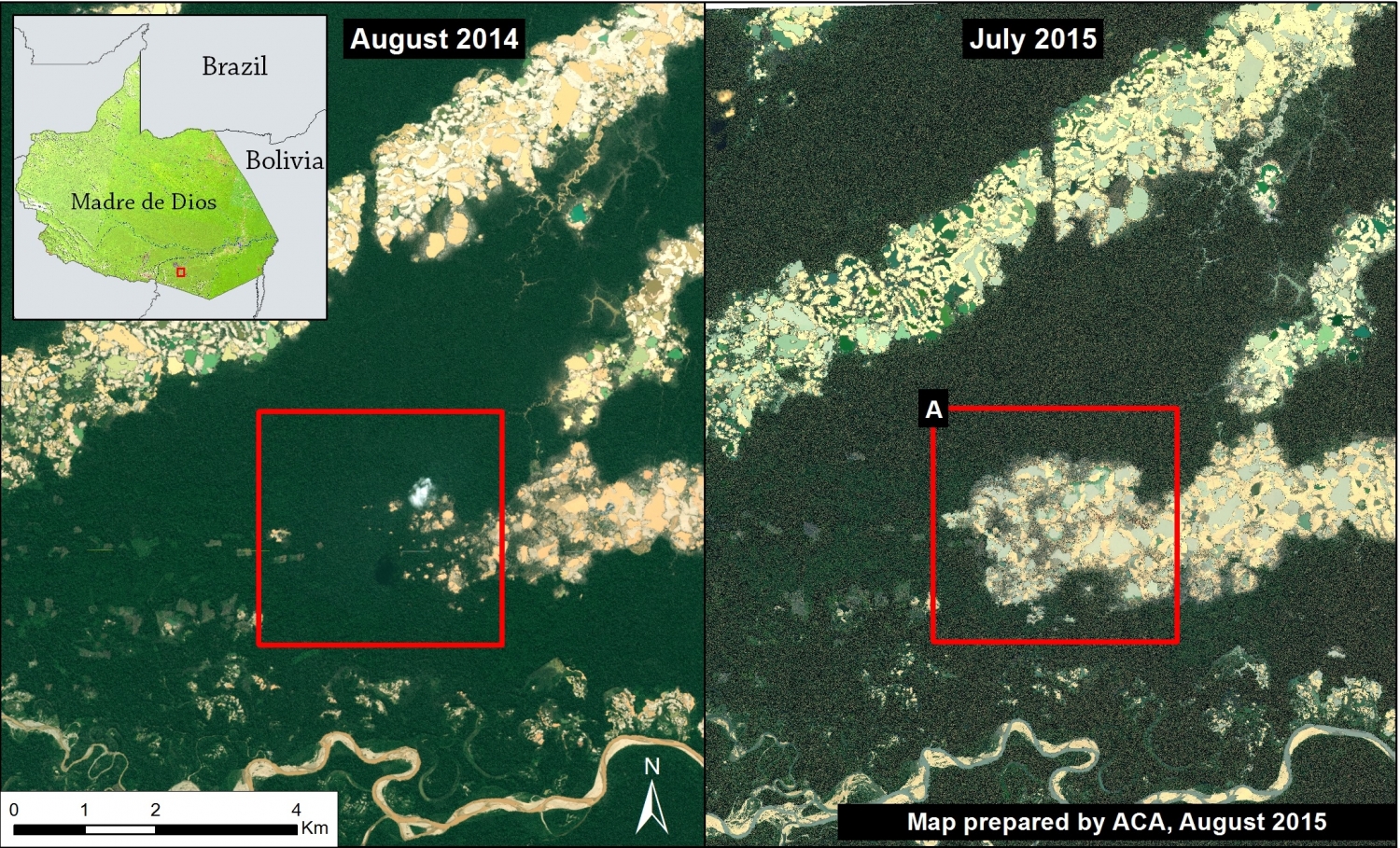

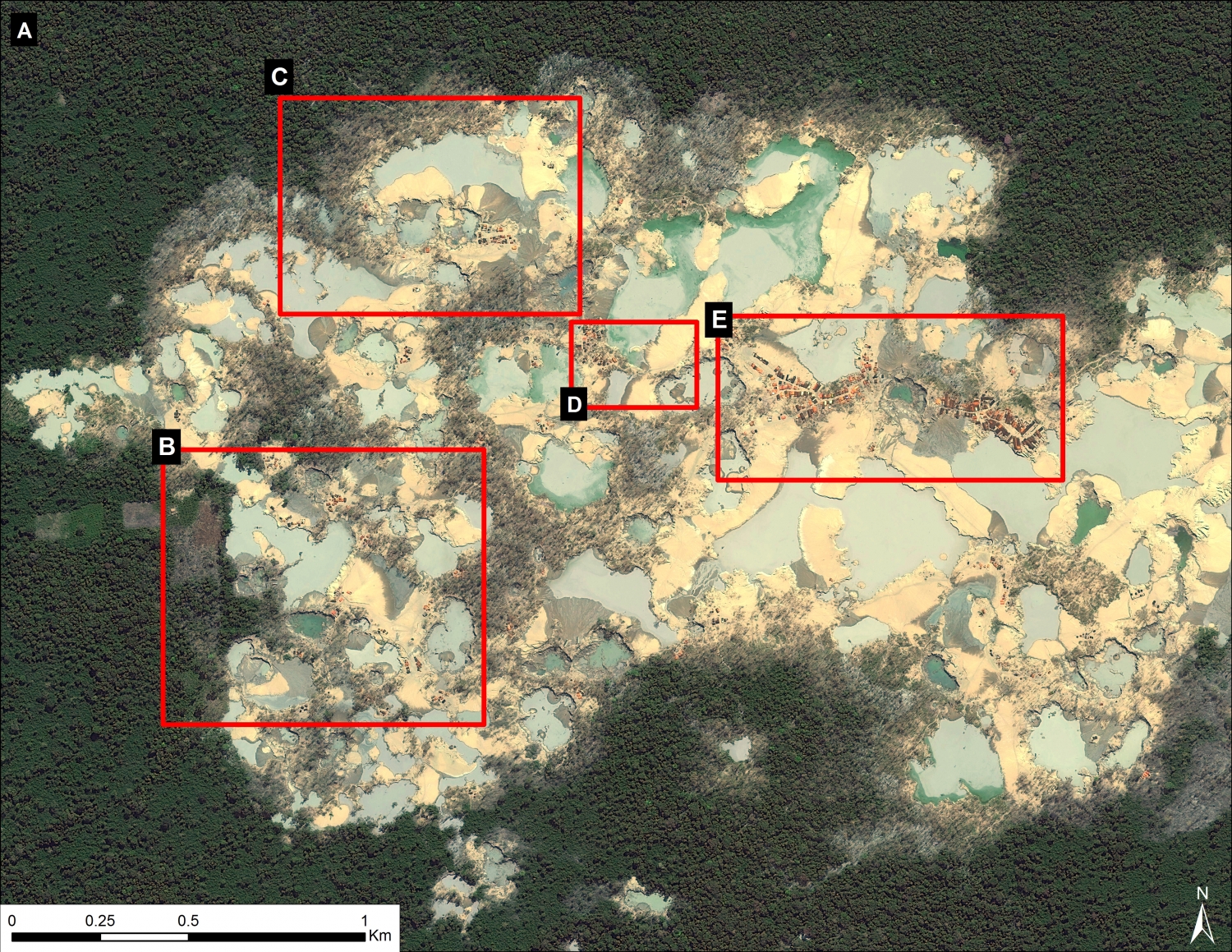

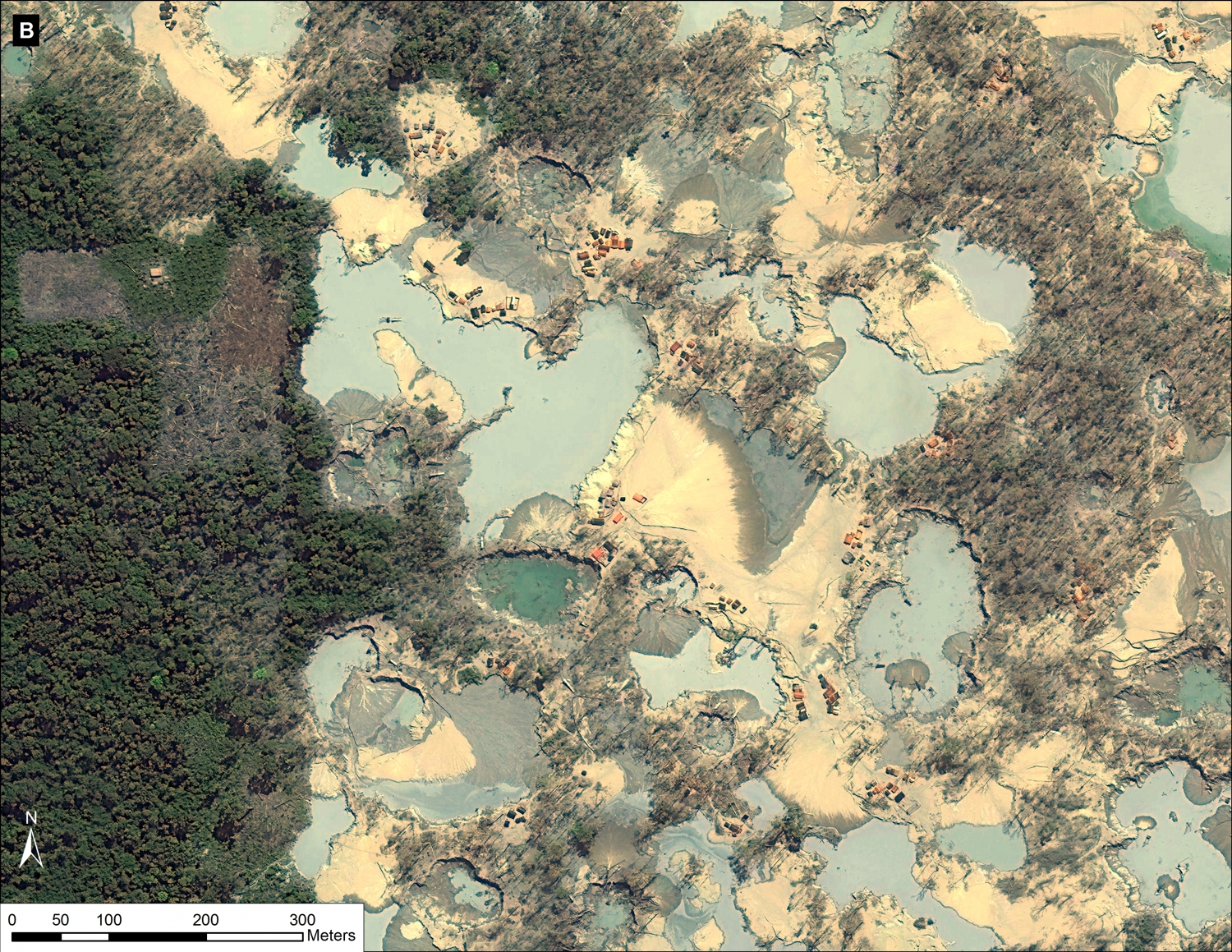

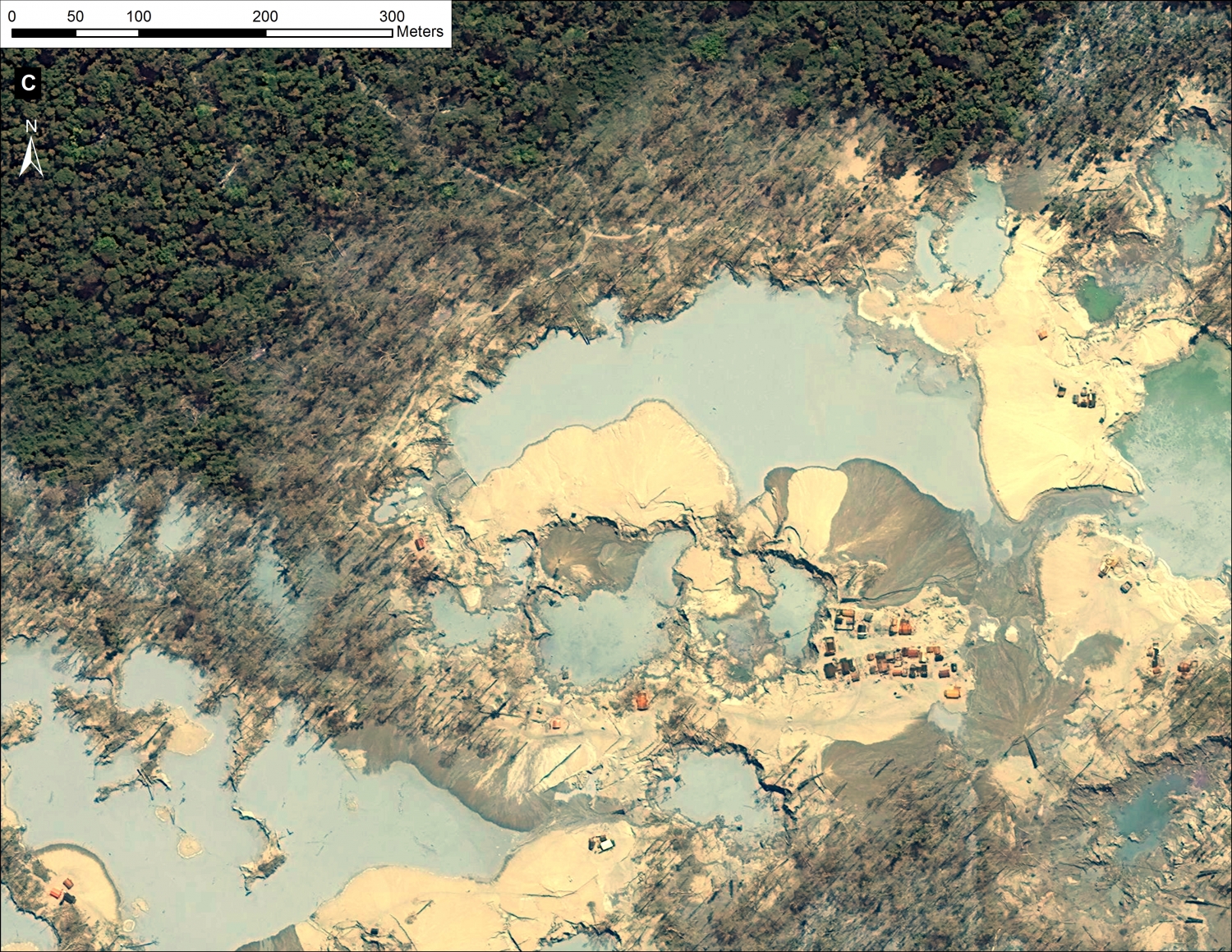

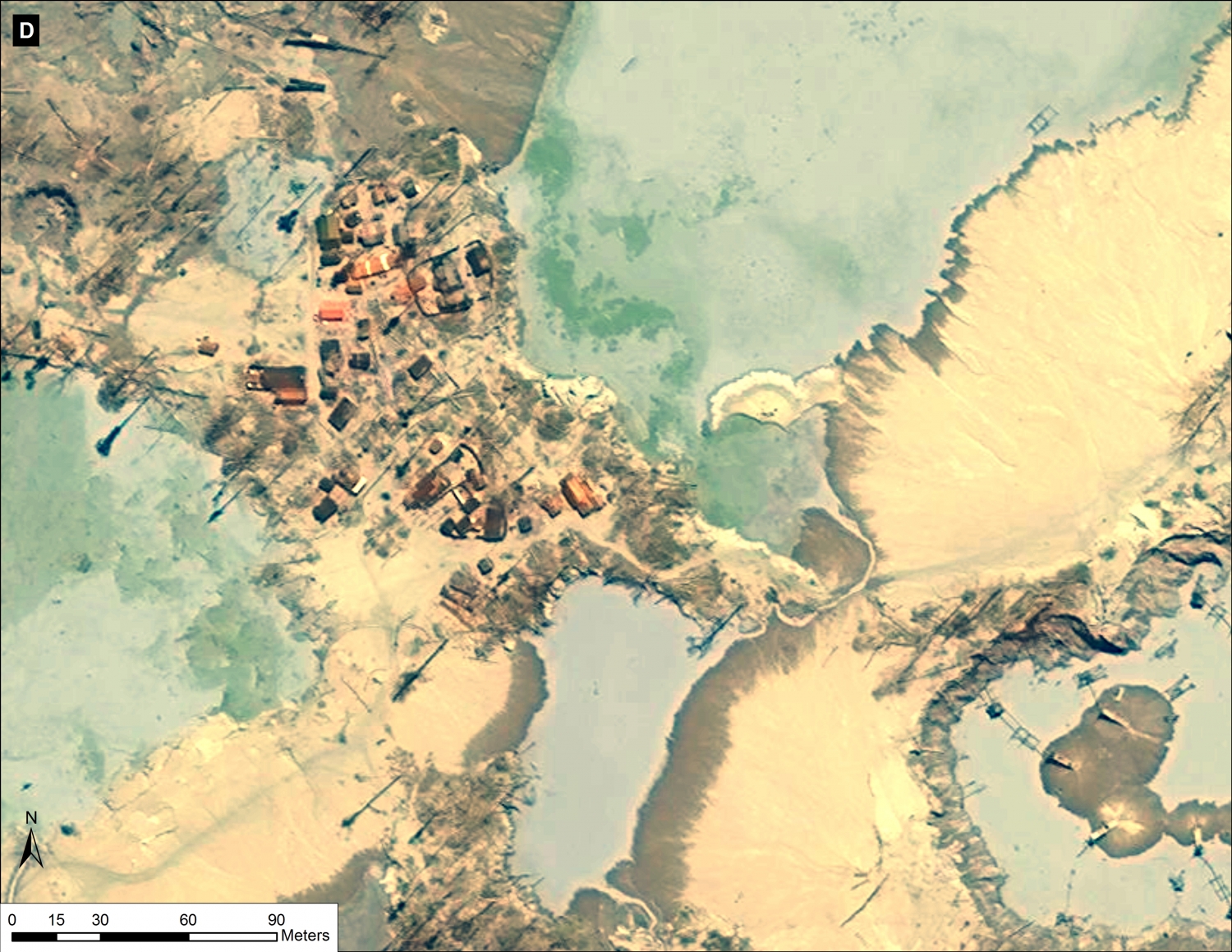

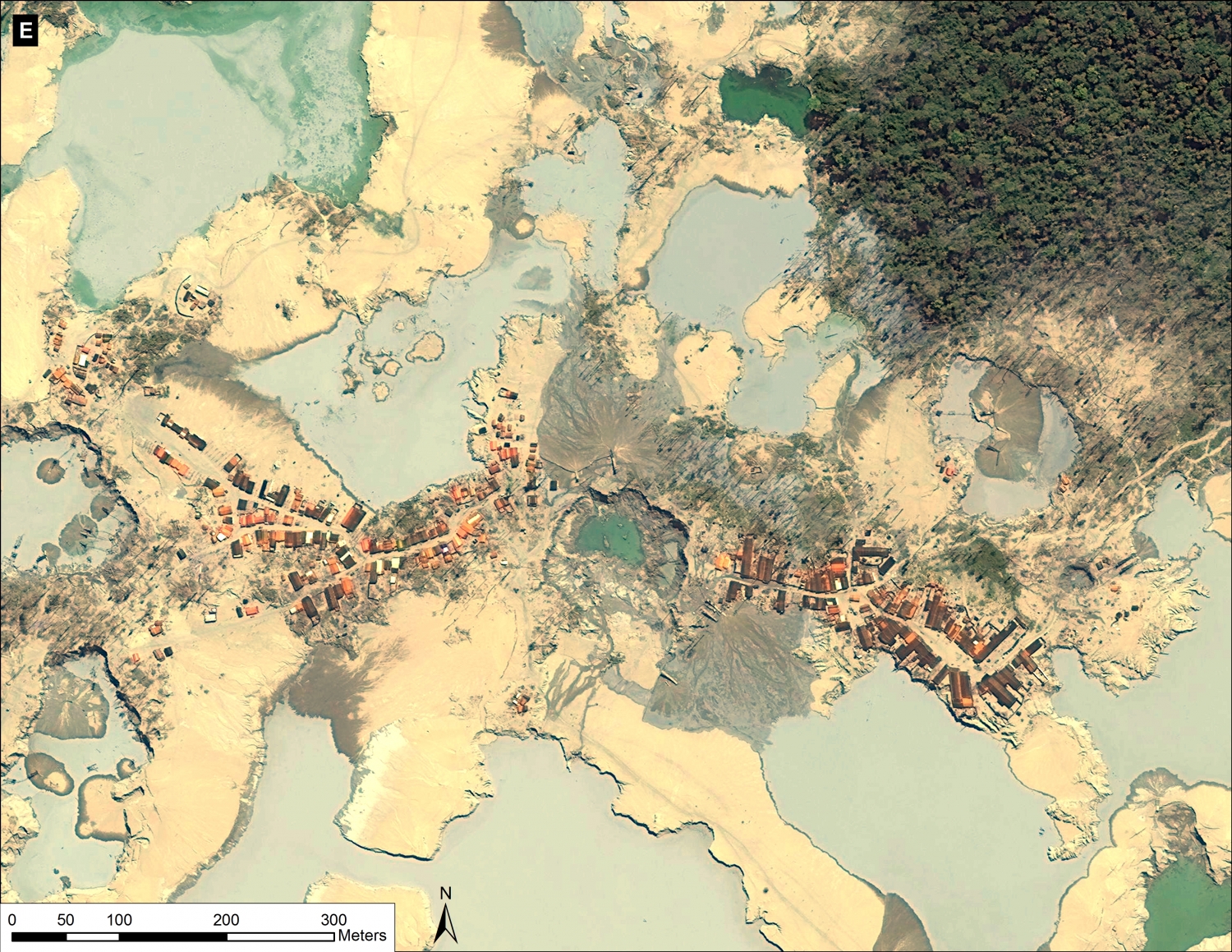

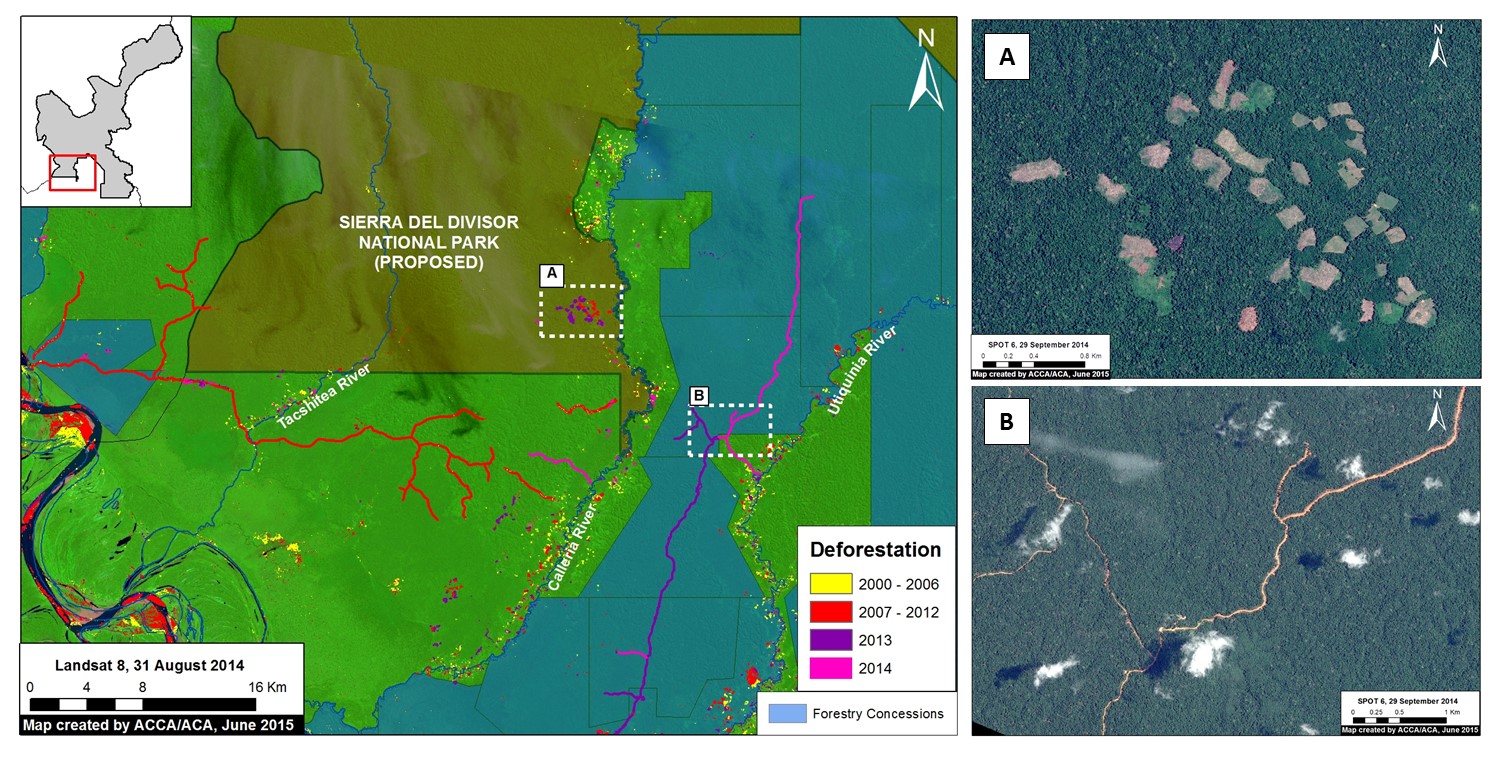

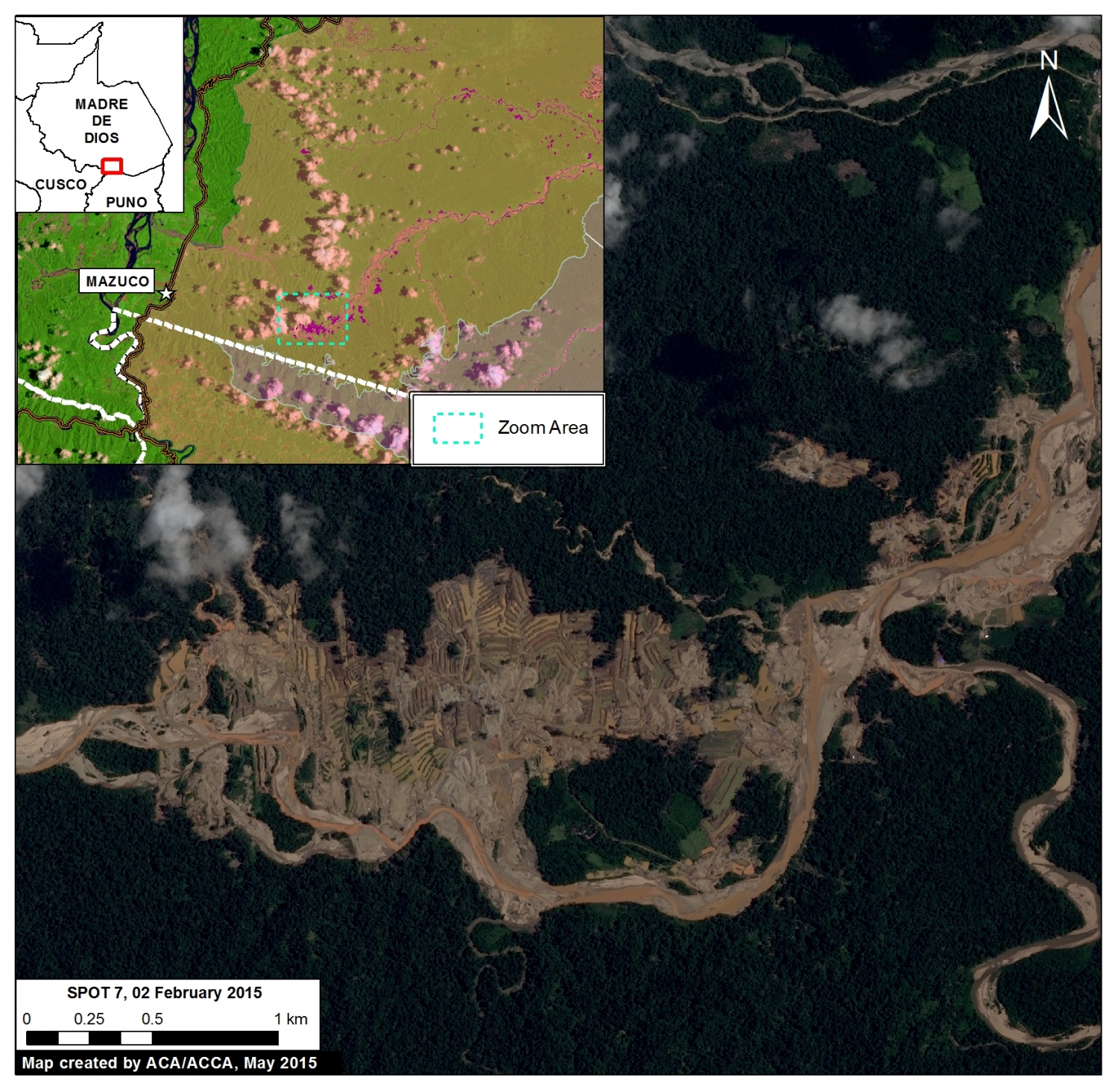

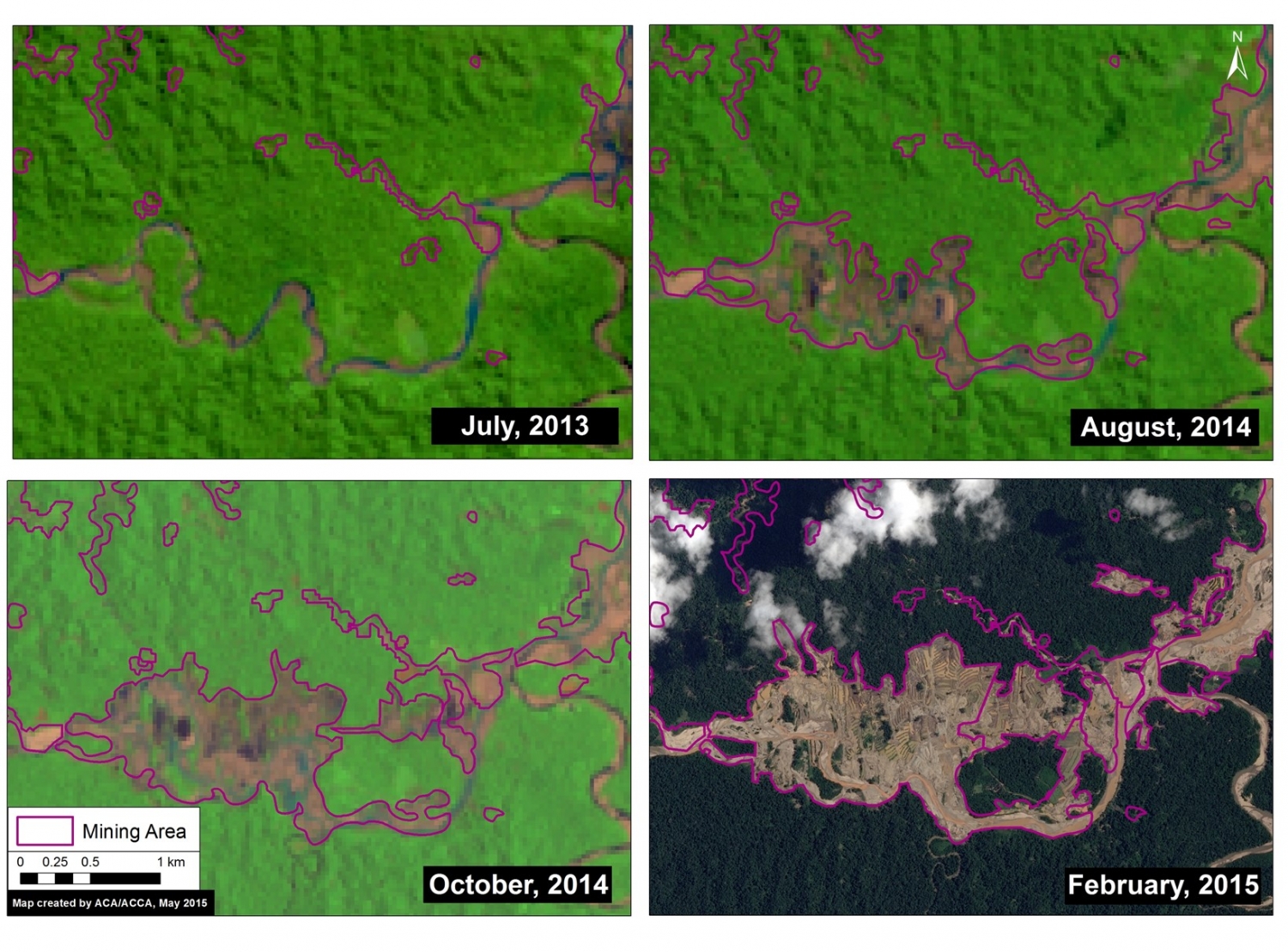

The Amazon Conservation Association released high-resolution images showing the intensity of illegal gold mining in La Pampa, Madre de Dios.

Government Action

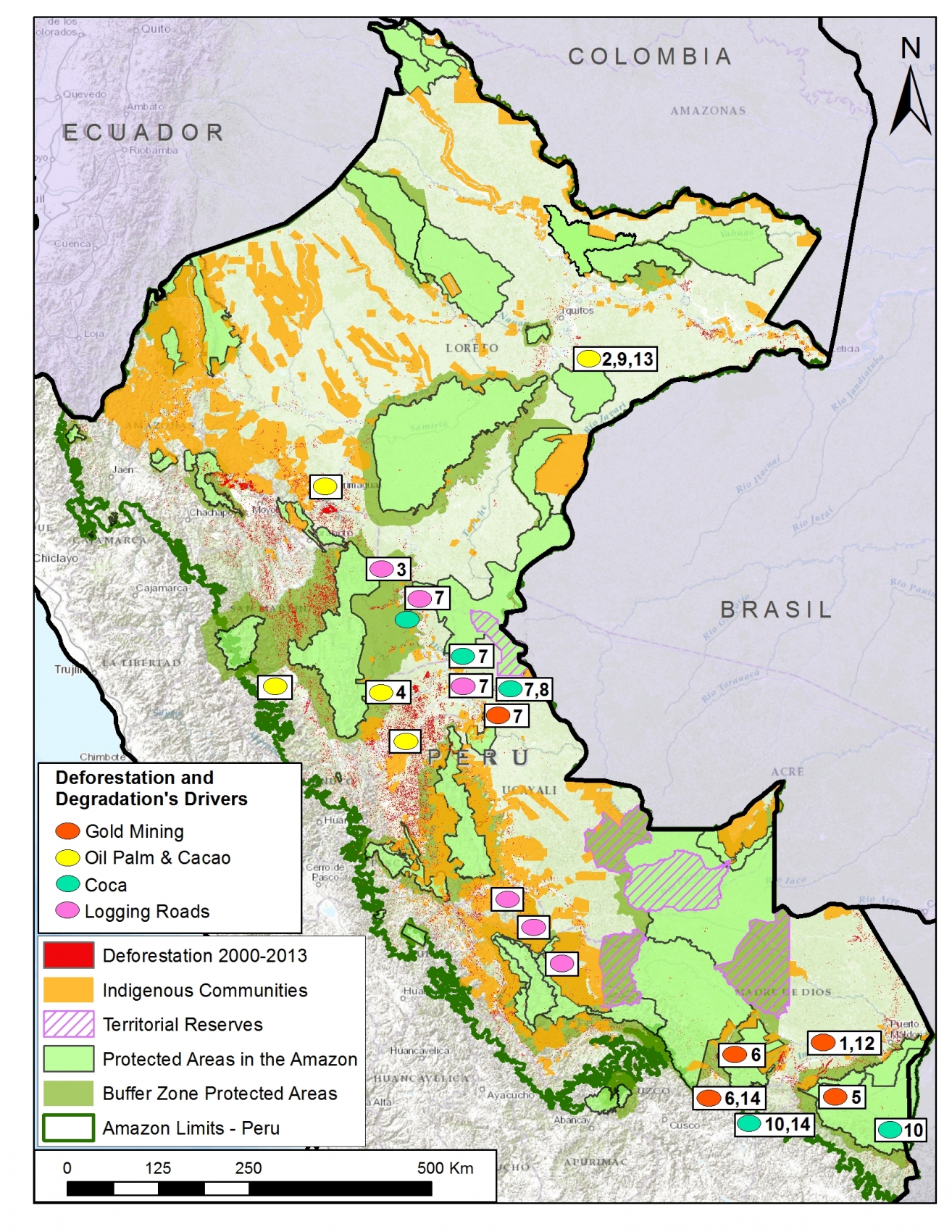

- In August, a raid against illegal mining occurred in the Santiago Pampa zone in Sandia, Puno. District attorneys specializing in environmental issues worked in coordination with the National Police to locate and destroy the settlement. The District attorneys confirmed that the water used to wash the ore was not treated before entering the River, resulting in contamination by heavy metals. [1]

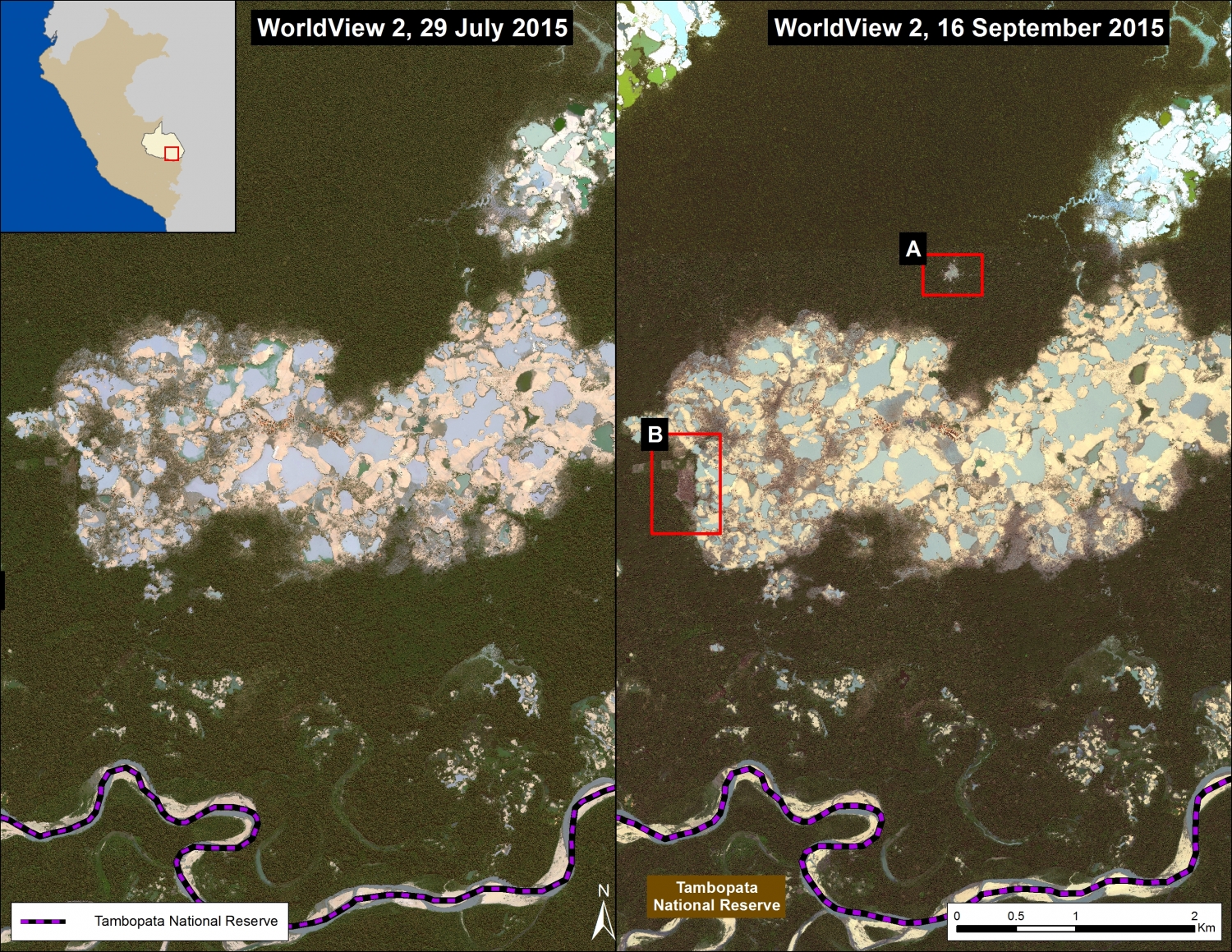

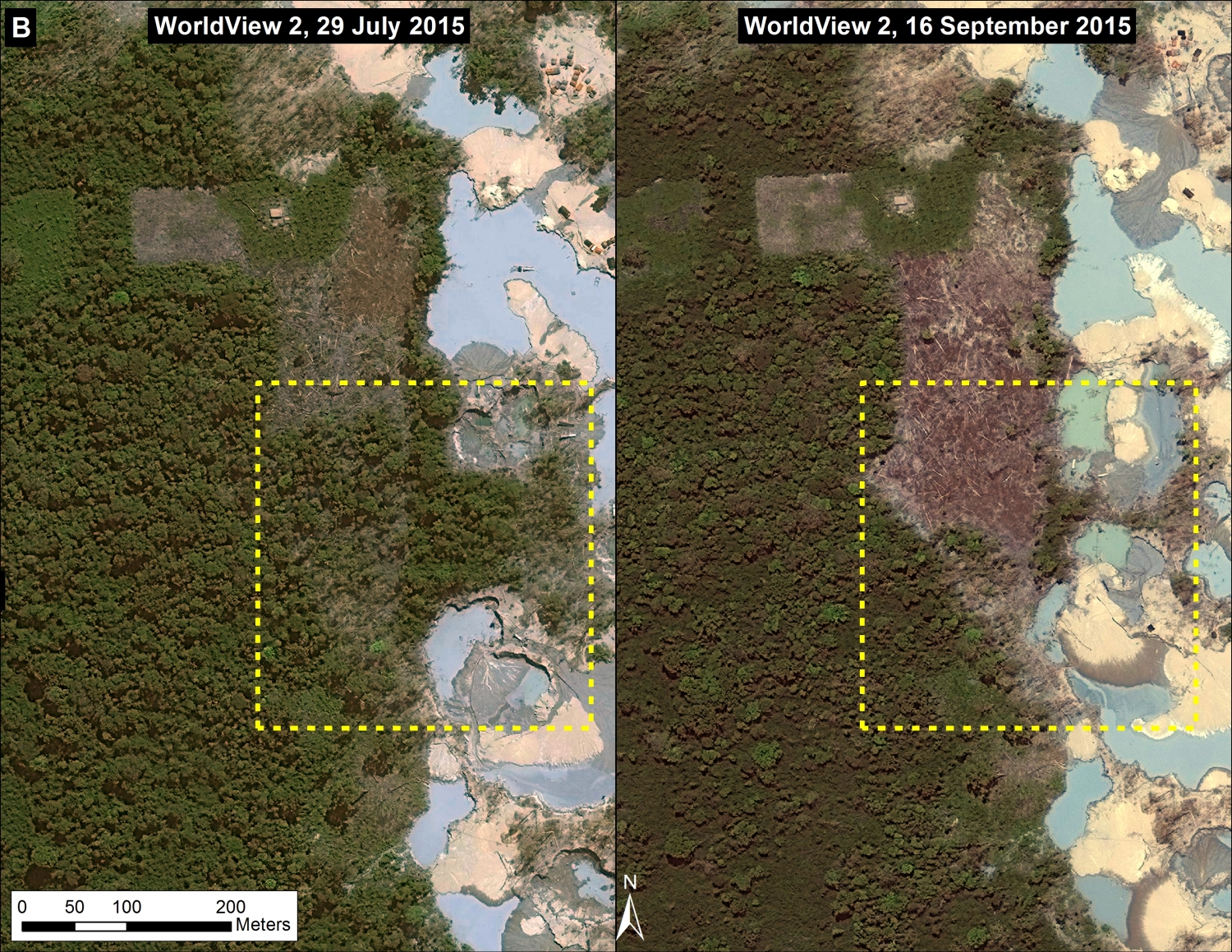

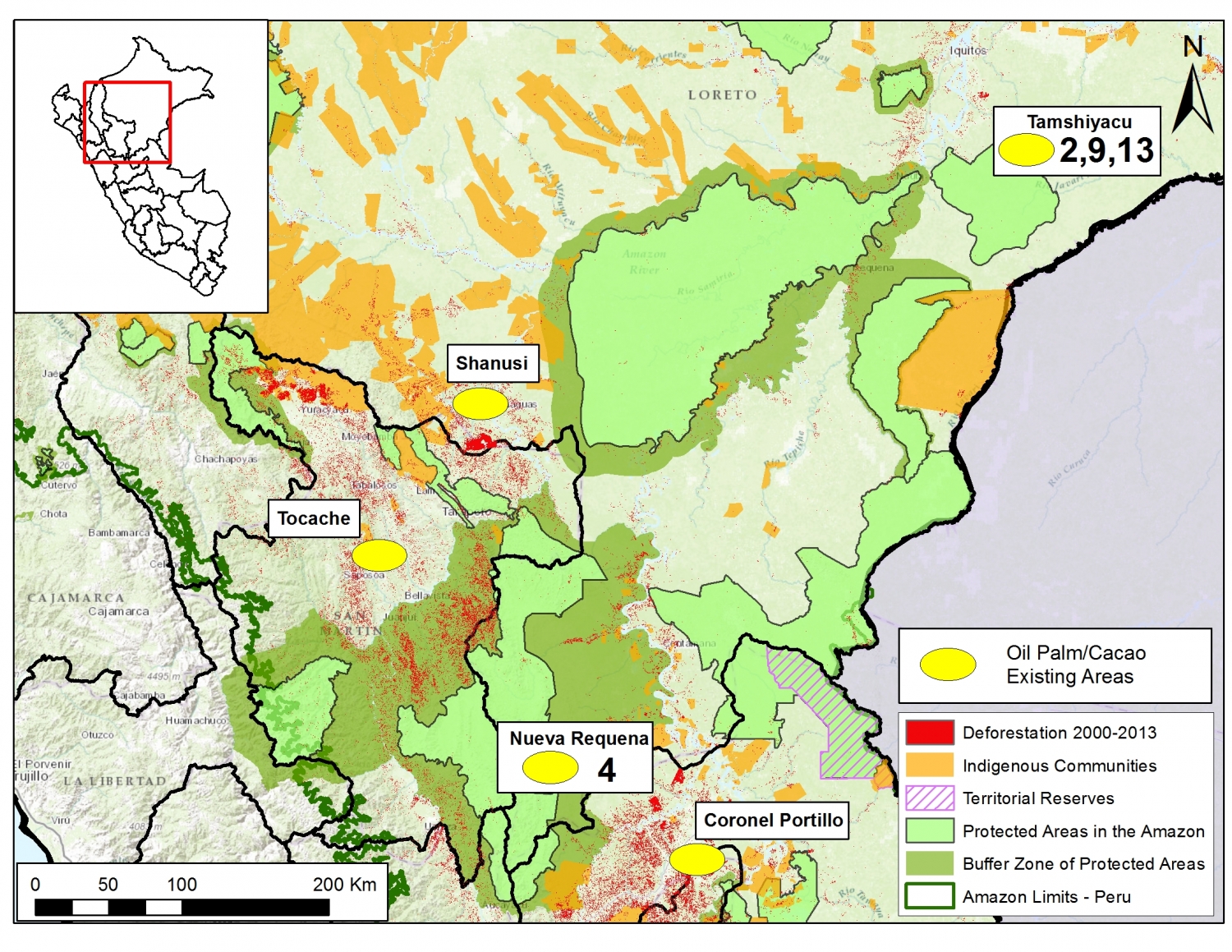

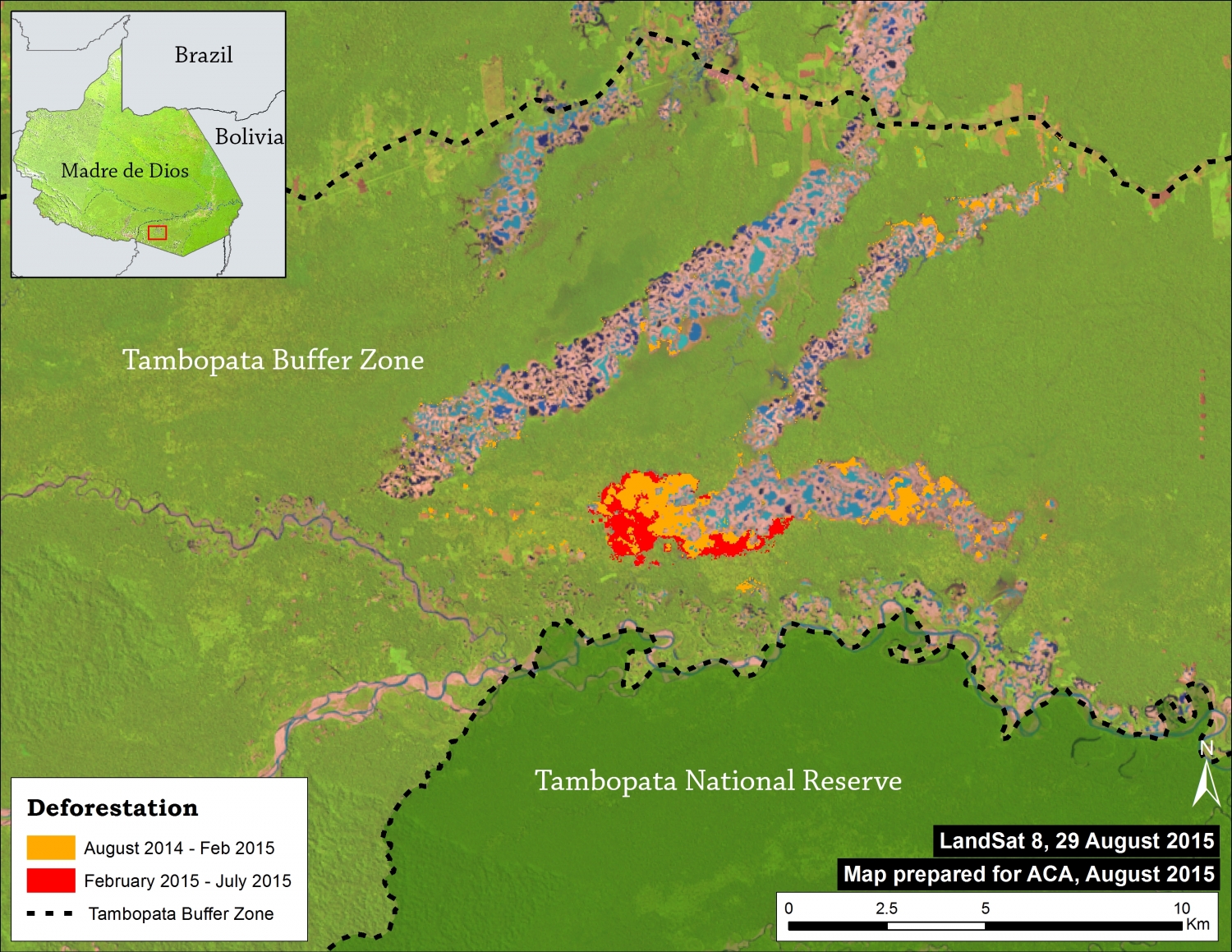

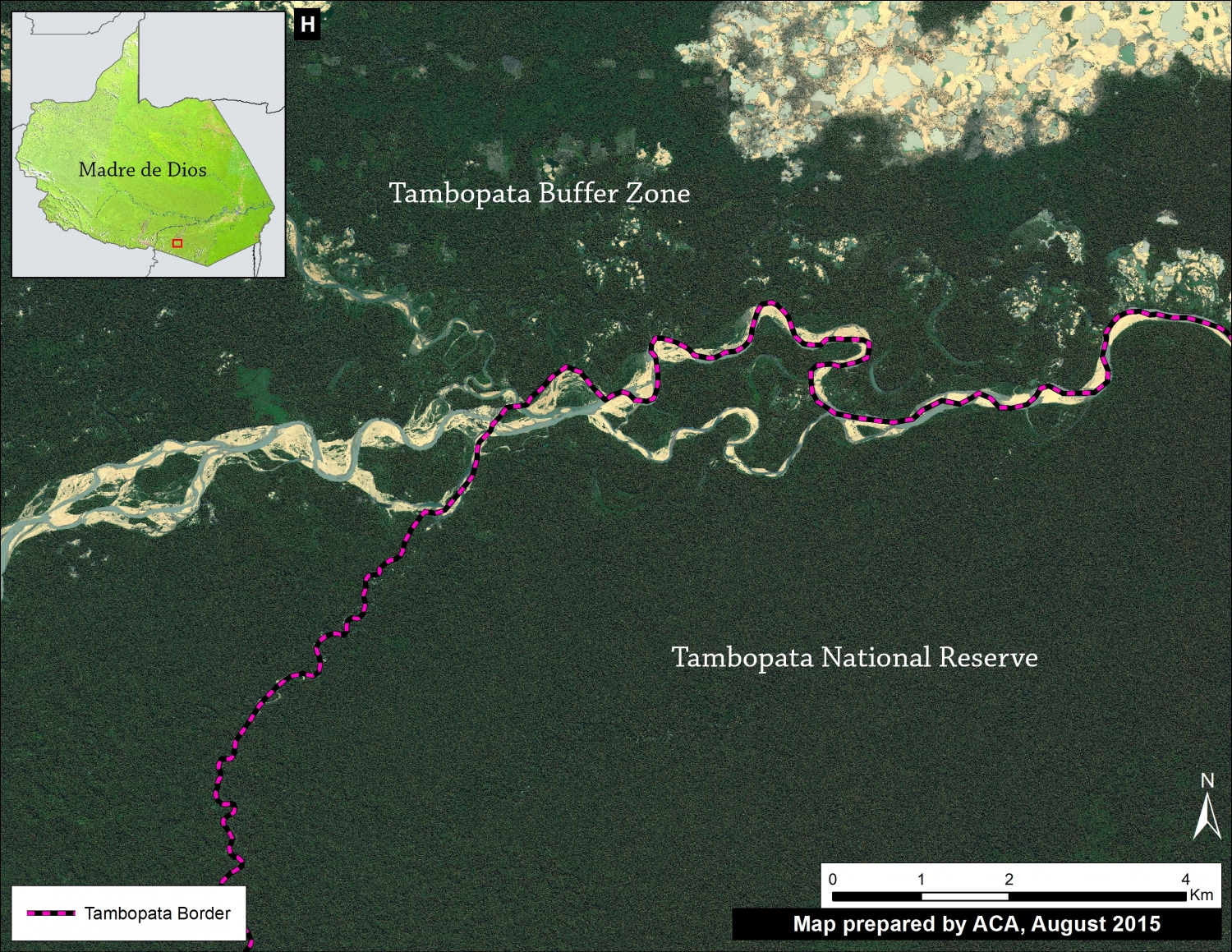

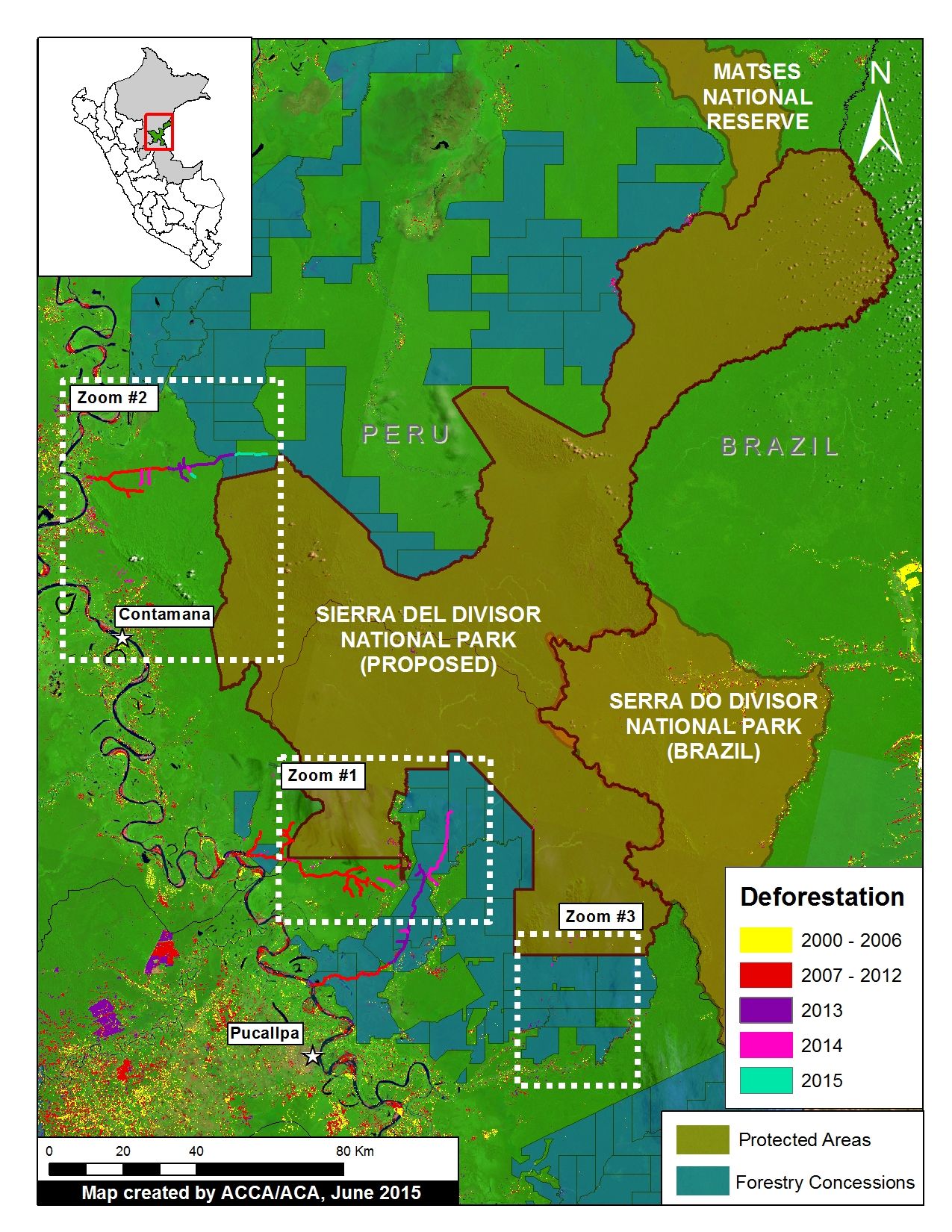

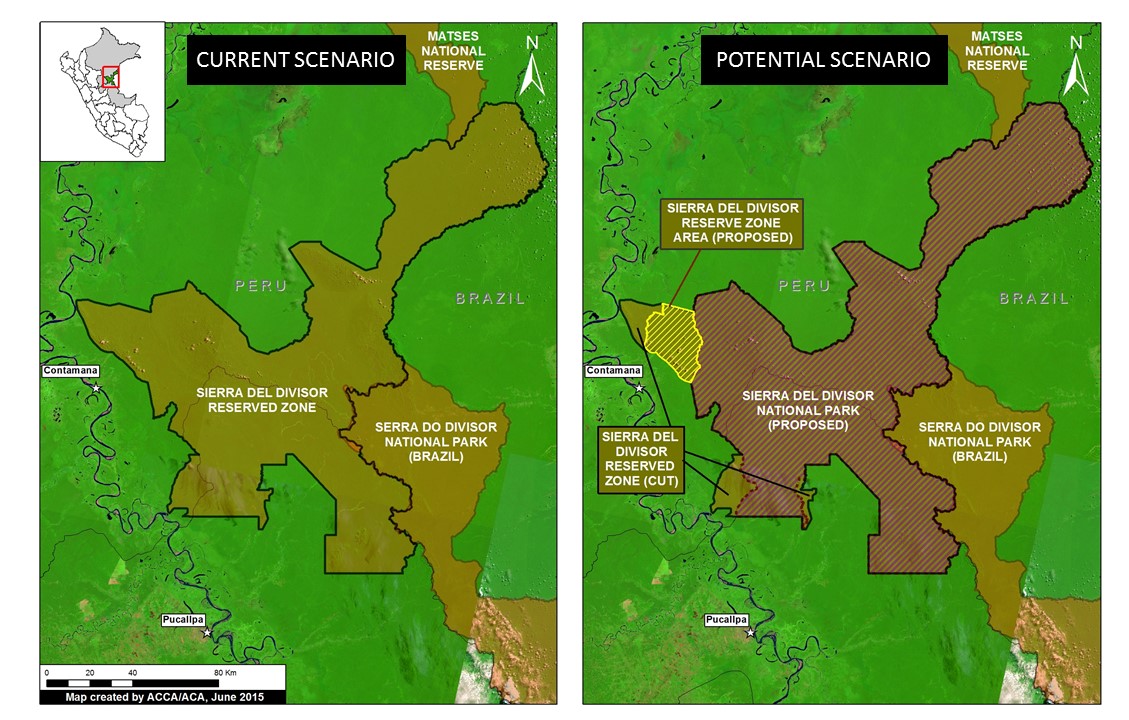

- In the beginning of September, a government operation against illegal mining was carried out in Tambopata, Madre de Dios. During the intervention, two people were detained, dozens of pieces of machinery were destroyed, and 250 milliliters of mercury were confiscated. An official from the Presidential Council of Ministers (PCM) stated that they will intensify actions to achieve the eradication of illegal mining in Madre de Dios, particularly in the buffer zone of the Tambopata National Reserve. [2] So far this summer, there have been three significant raids in Peru combatting illegal mining settlements. However, illegal mining camps are often rebuilt in the same area almost as soon as the government intervention has ended.[3]

- 1,300 police agents broke into 40 illegal mining camps in La Pampa and detained 41 miners. These camps had been destroyed after the raid in July, but were quickly resettled by miners.[4]

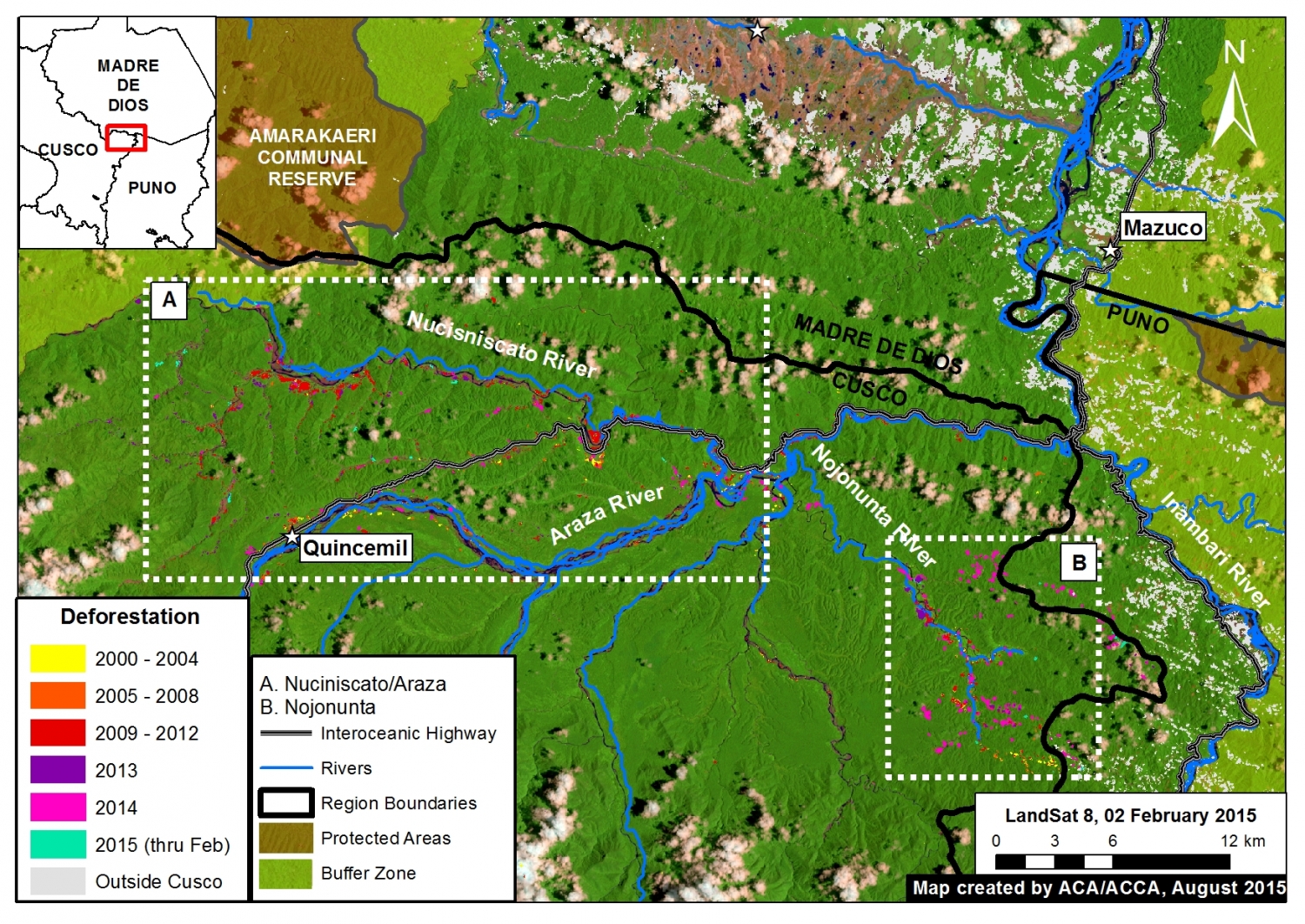

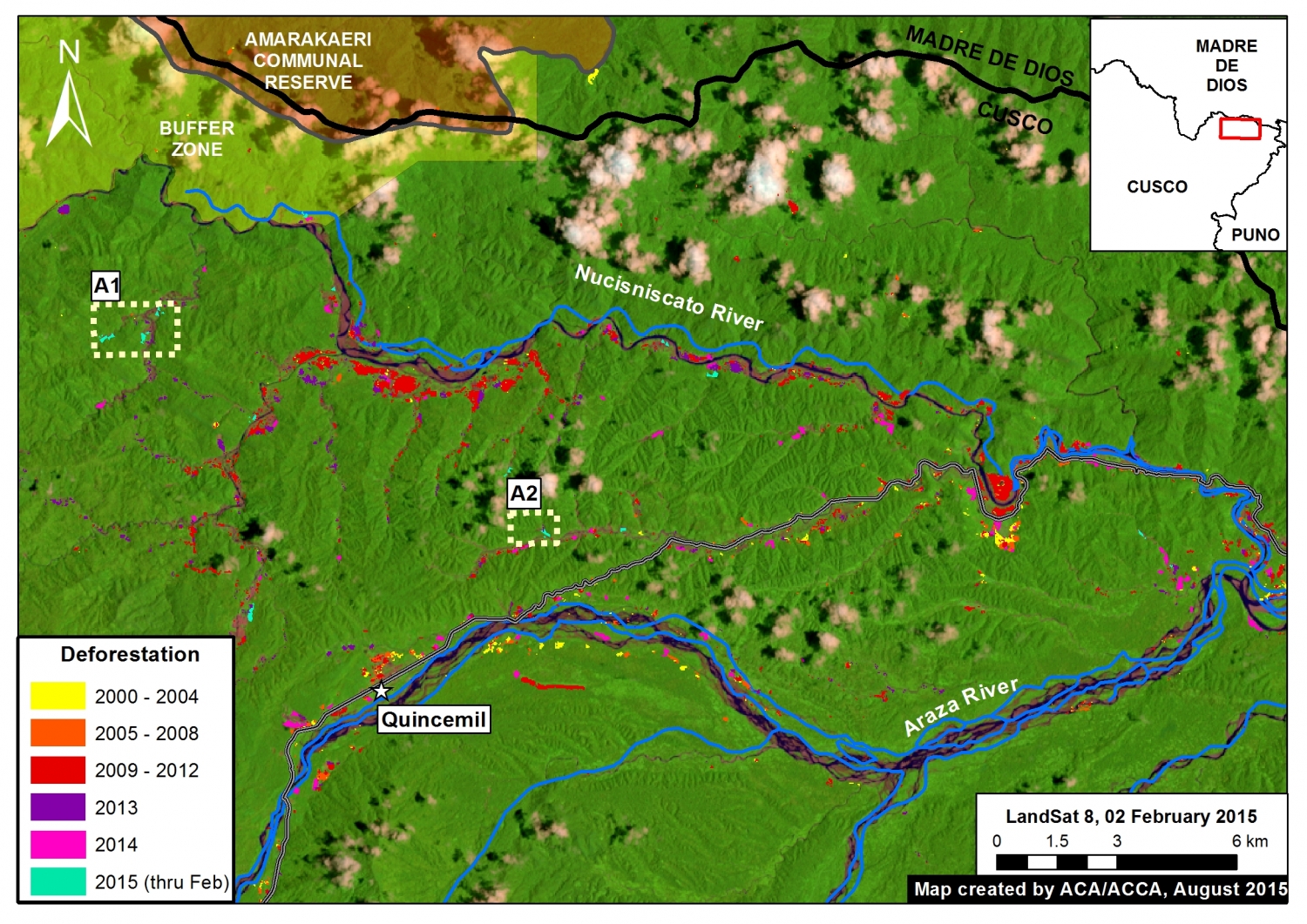

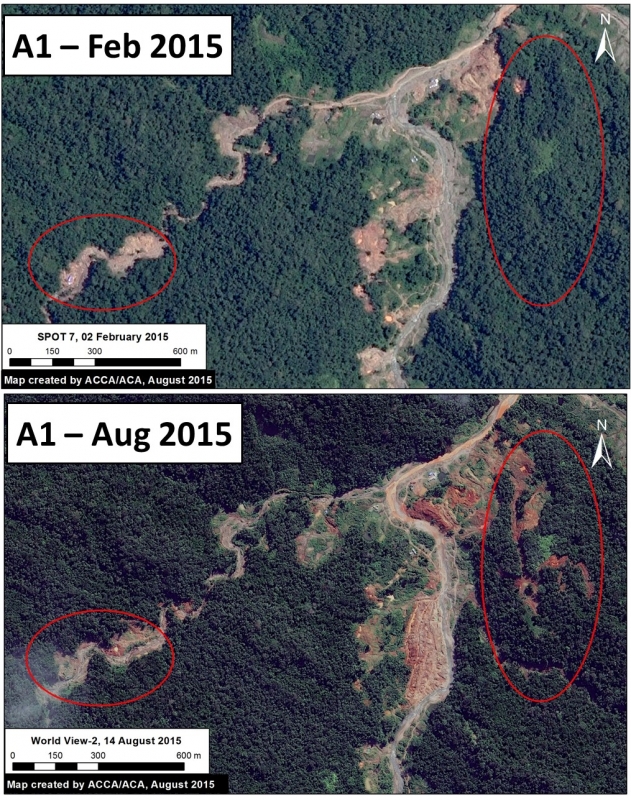

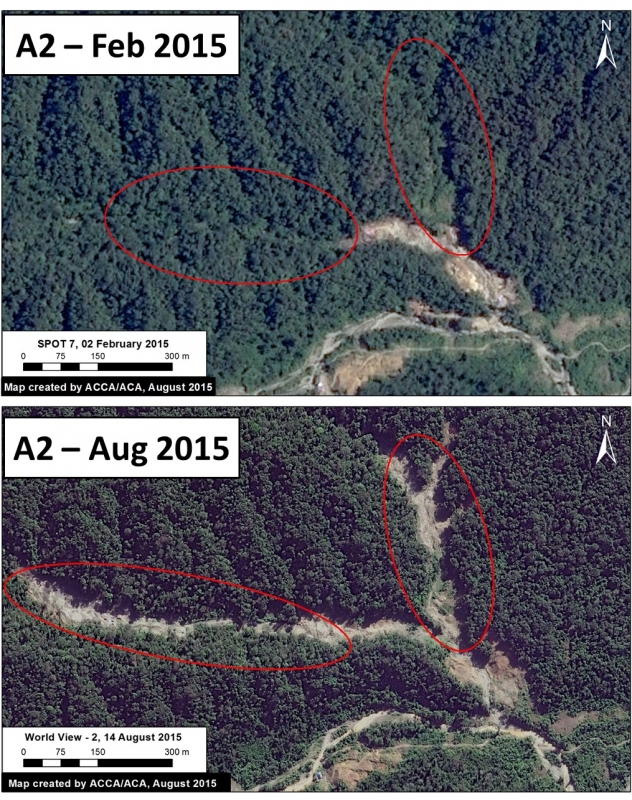

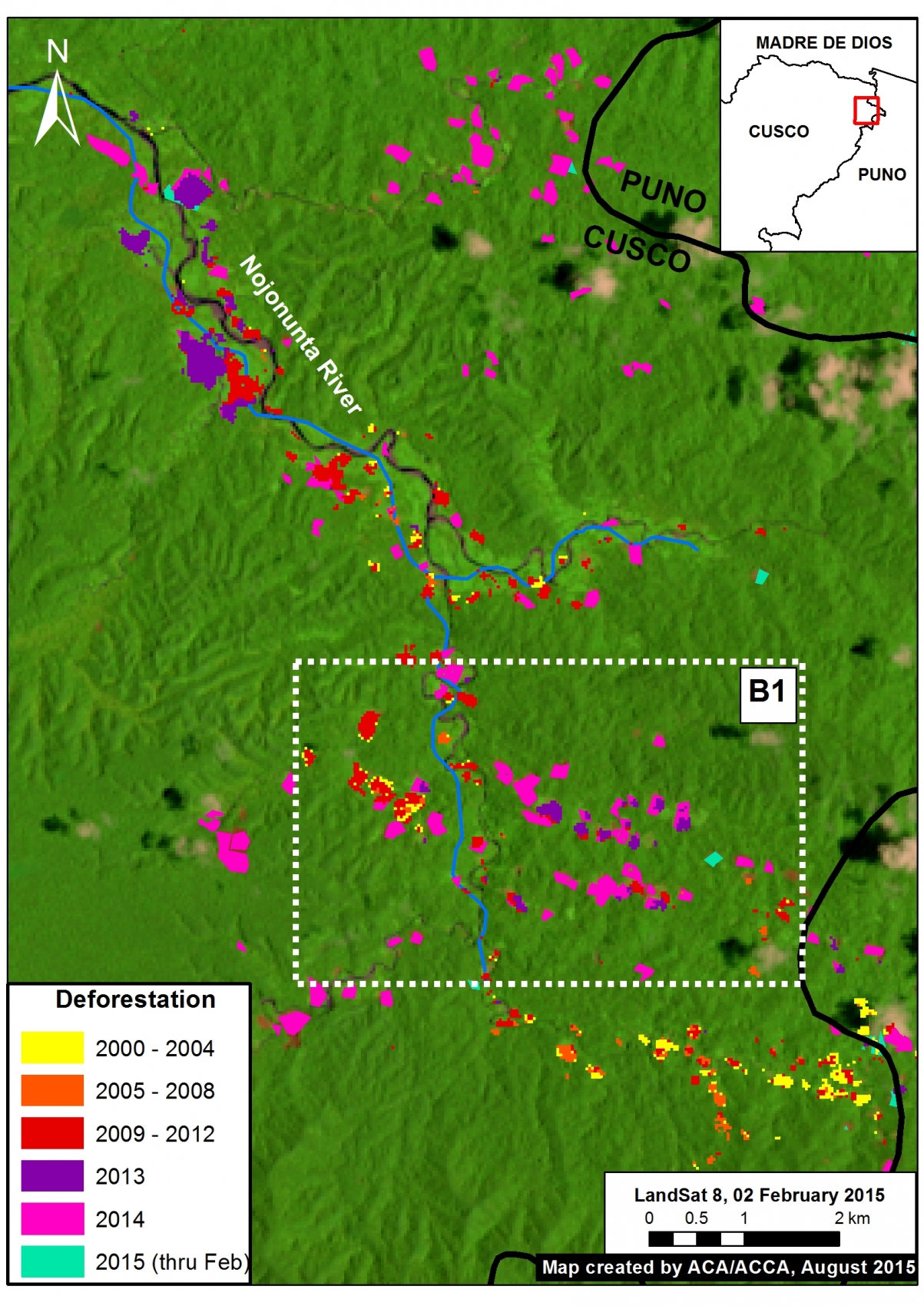

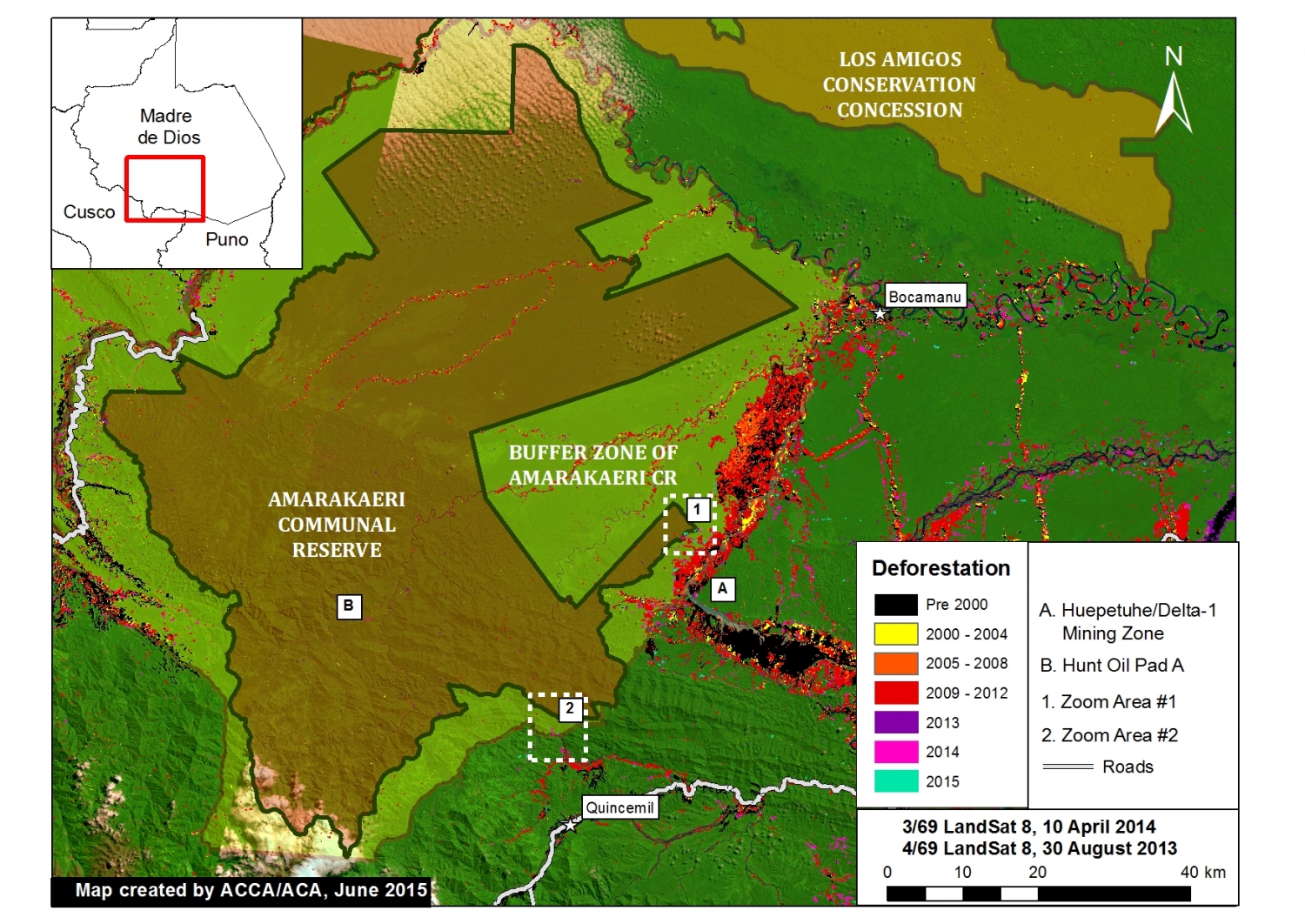

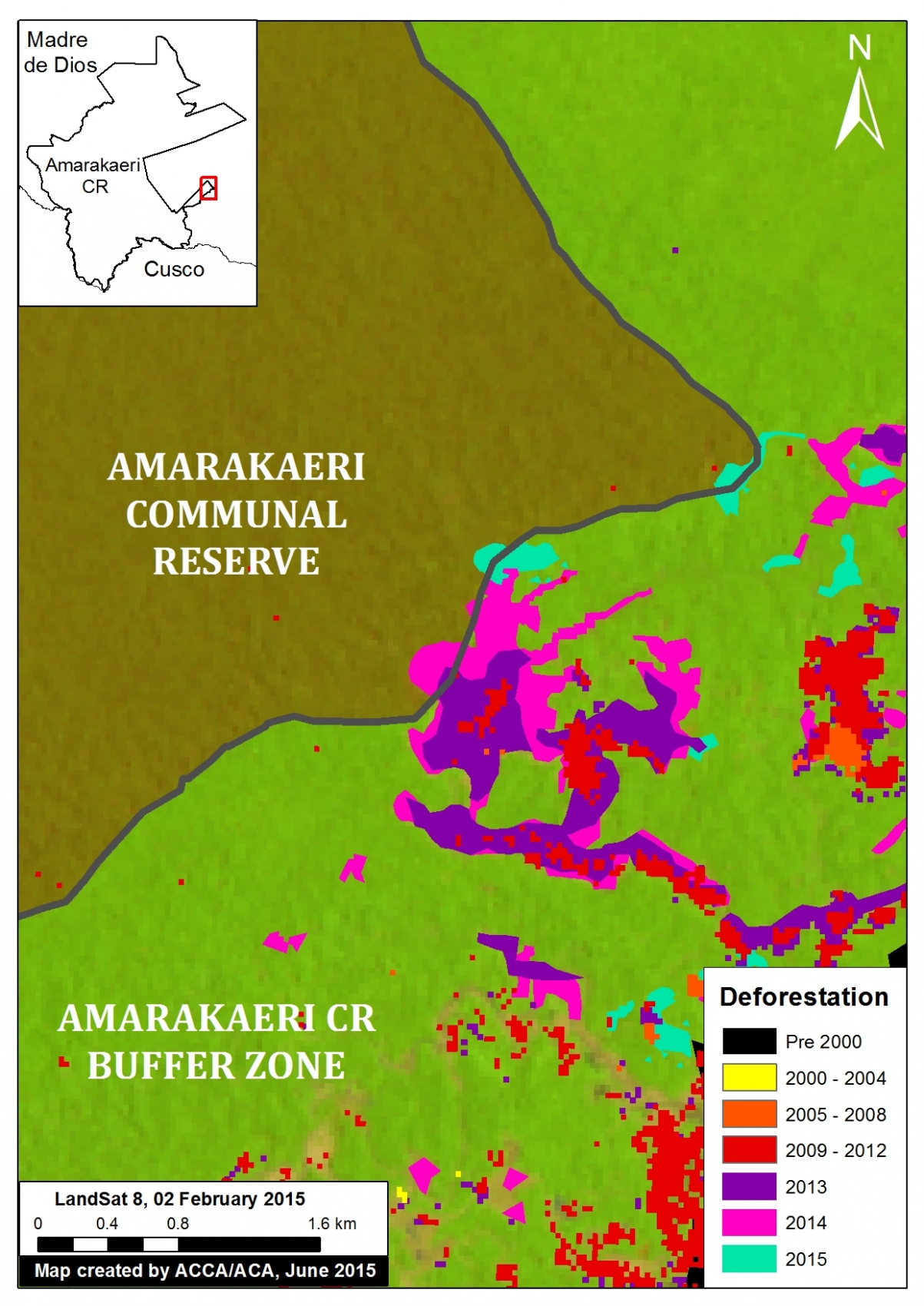

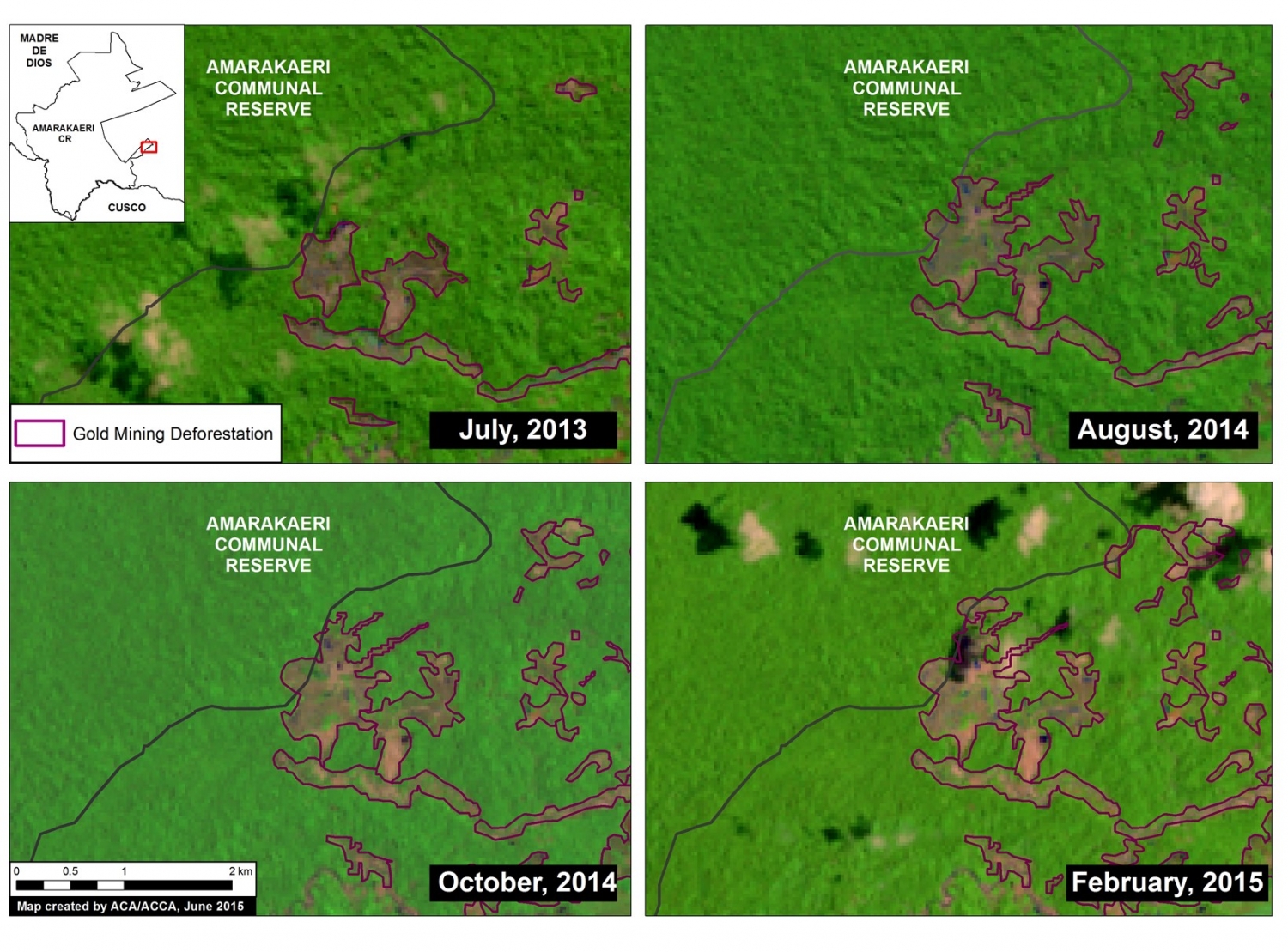

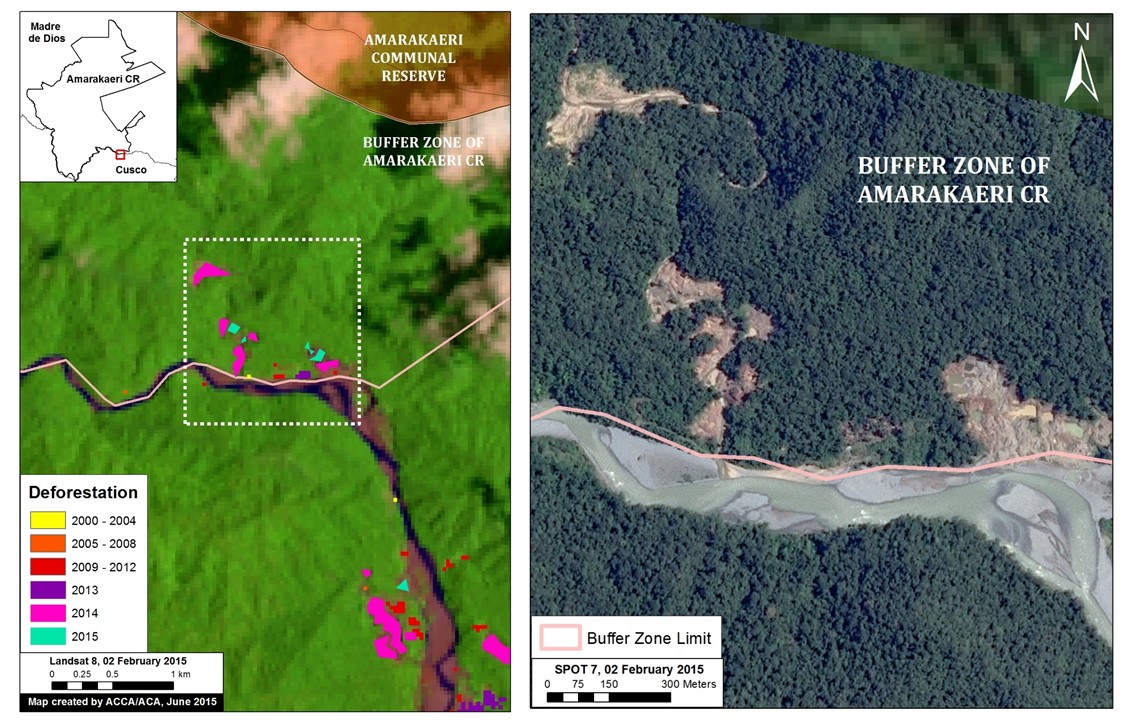

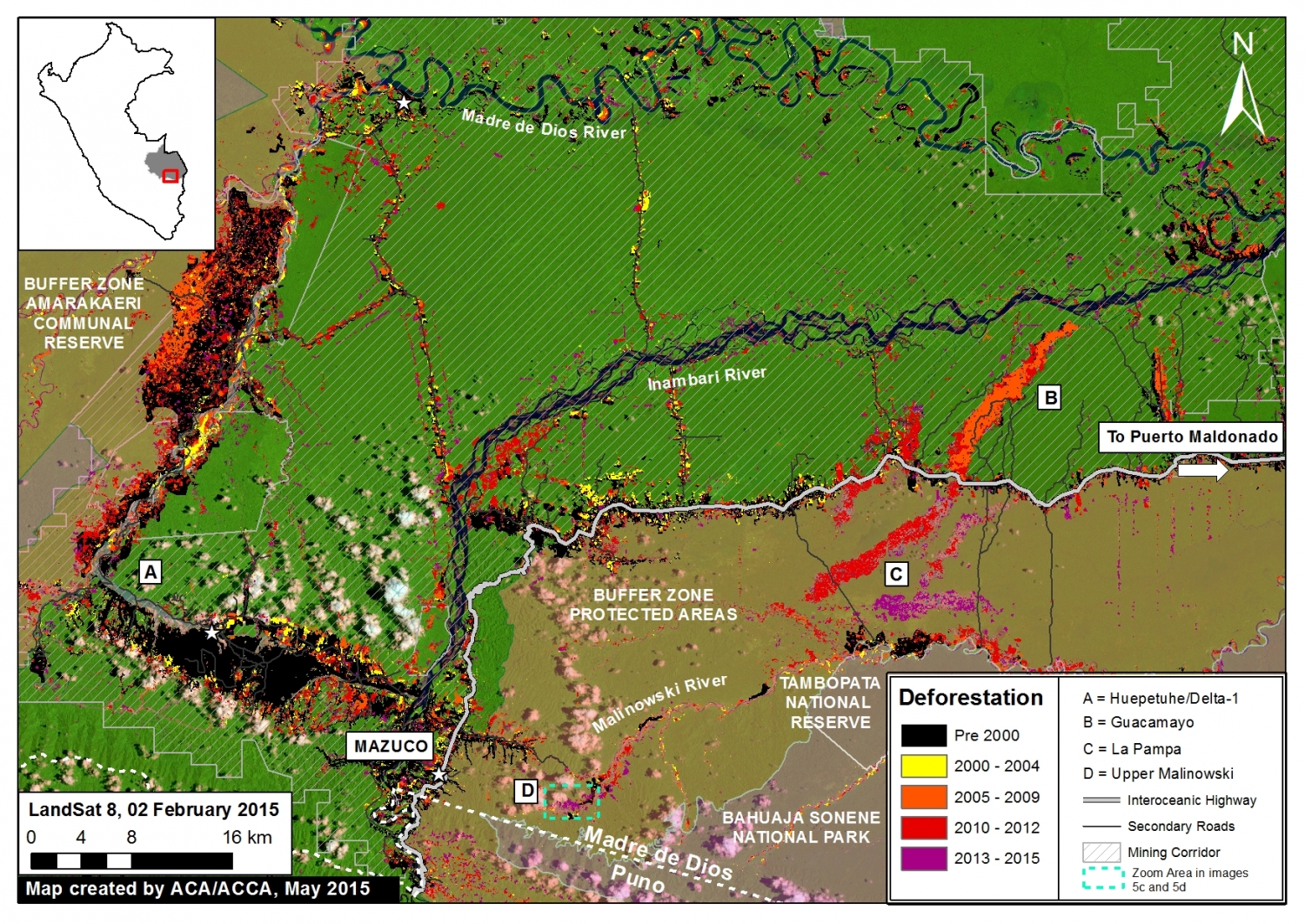

- Over the next 3 years, SERNANP will be investing four million soles to protect three natural protected areas (the Tambopata National Reserve, the Bahuaja Sonene National Park, and the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve) from the threat of illegal mining. This includes installing patrol posts, hiring forest rangers, and buying boats. There are currently only 34 forest rangers in the Tambopata National Reserve, 13 in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, and 12 in the Bahuaja Sonene National Park.[5] Shortly after ACA released images depicting illegal mining in the buffer zone of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, SERNANP also announced that they will be fortifying security actions specifically in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. This includes increased funds for aerial patrols and a shelter for personnel to spend the night. [6]

- In October, there was a strike in Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios, to express disagreement and ask for the repeal of legislative decrees issued by the central government to control the purchase and sale of fuels as one of the measures to combat illegal mining. The strike consisted of 300 protestors, mostly those that work in public transportation, and lasted for 48 hours.[7]

- Four men have been found guilty of illegal mining activities, and have been sent to 6 months in preventive prison for contaminating the Huacamayo ravine, located in Inambari, Madre de Dios. [9]

- The Minister of the Interior has approved three resolutions to amplify the intervention of the Armed Forces in Arequipa, Puno, Madre de Dios, and Junín for one month, in response to the possibility of violent protests linked to illegal mining. [10]

Deforestation

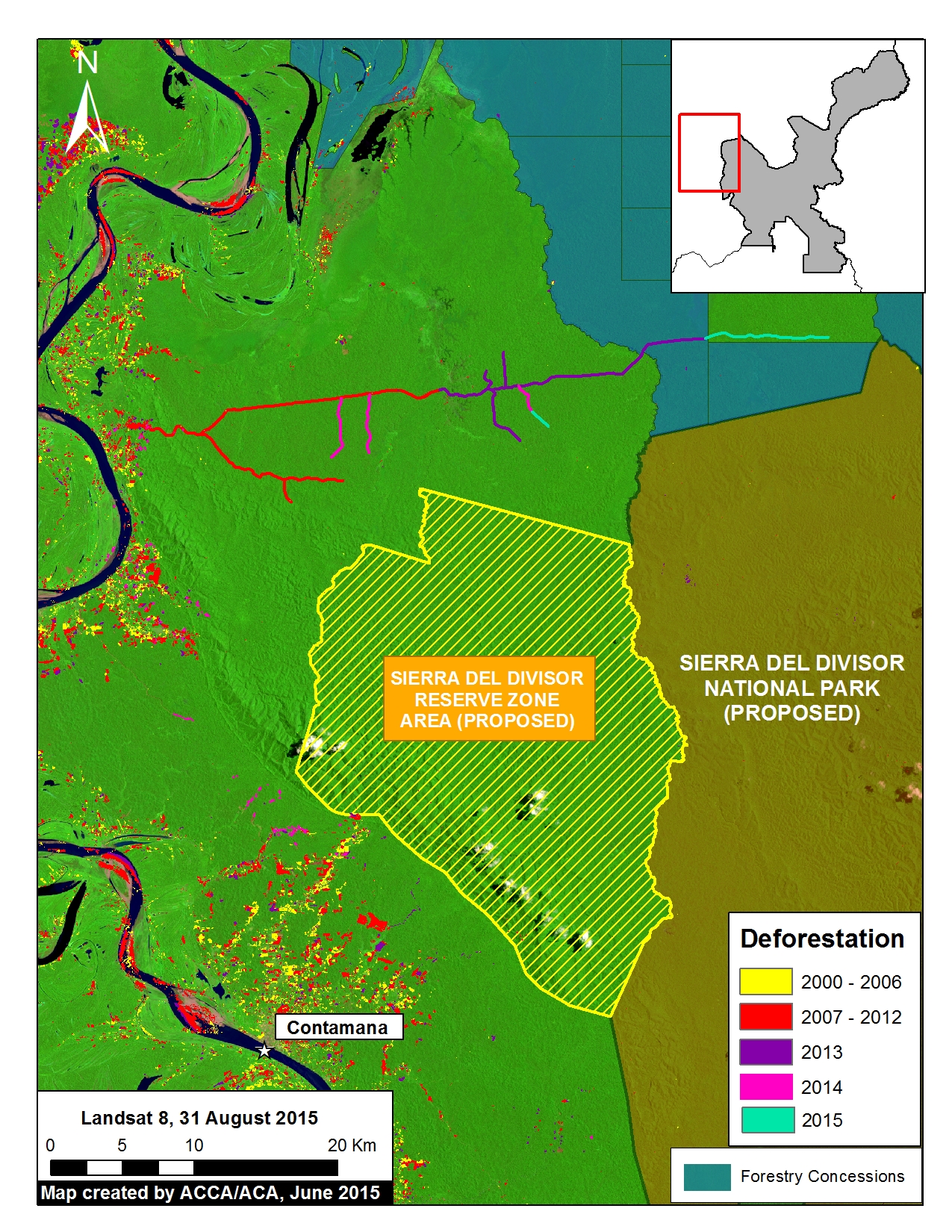

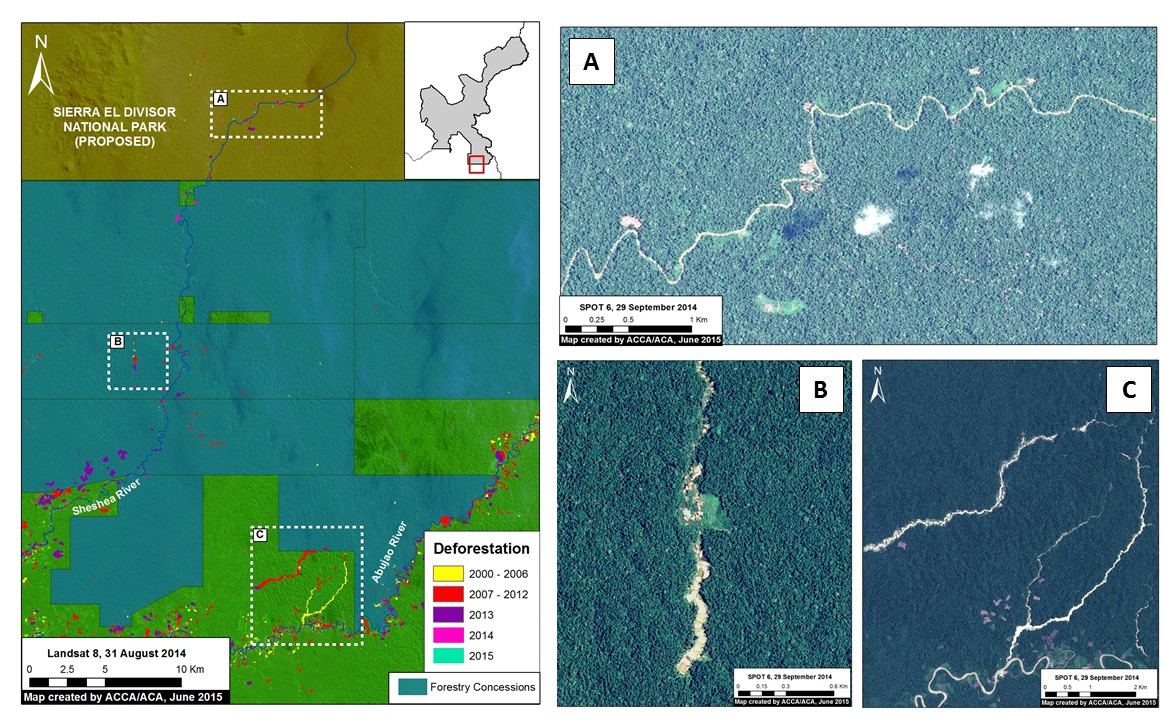

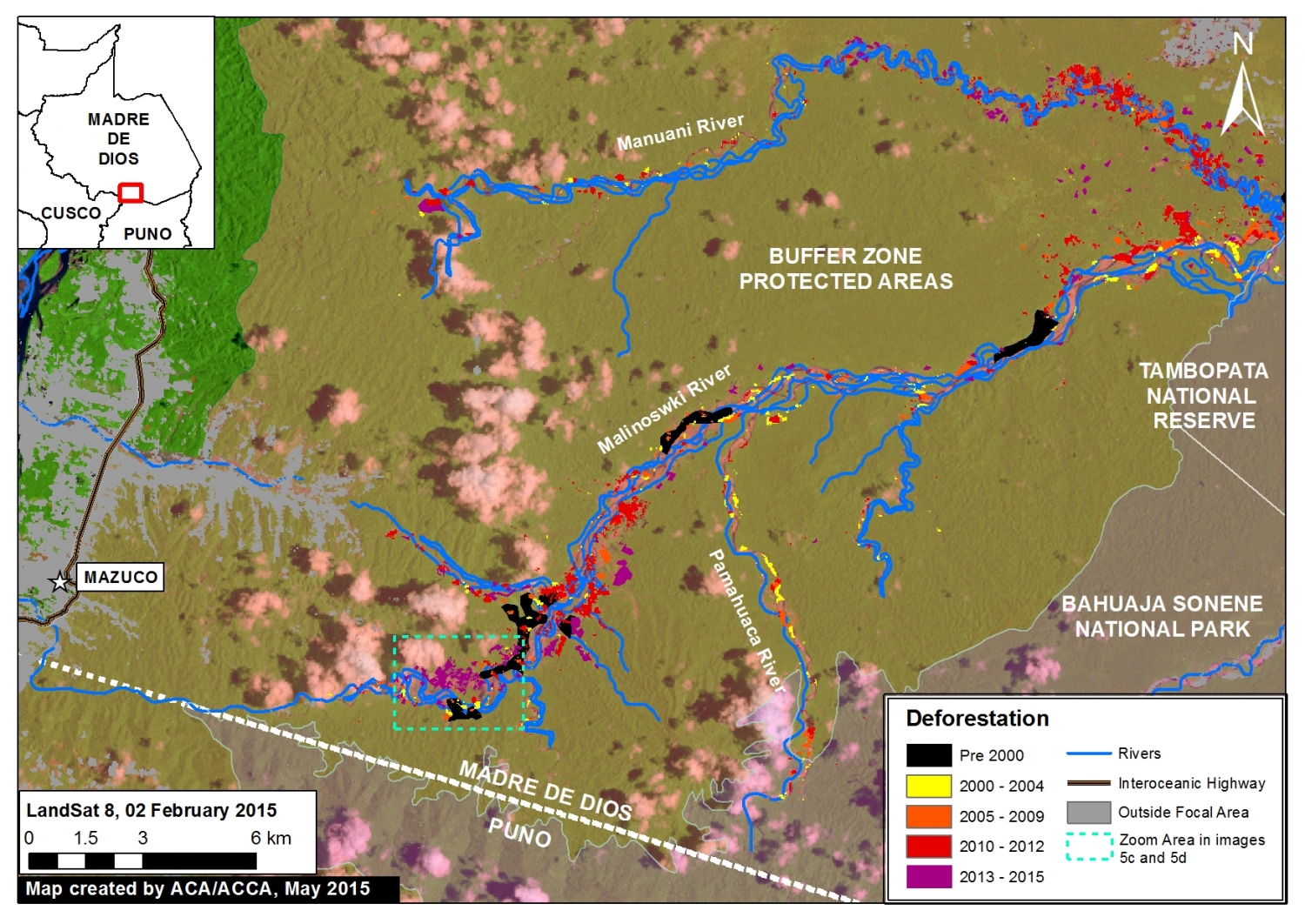

- The Amazon Conservation Association released images on their Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) website depicting high-resolution views of illegal gold mining in La Pampa, Madre de Dios. La Pampa is found inside the buffer zone of the Tambopata National Reserve. 725 hectares of land were deforested from August 2014 to July 2015, and 225 hectares of land were deforested from February 2015 to July 2015.[11]

International

- Peru and Bolivia worked together at their shared border to capture 21 illegal miners in September. Illegal miners in Peru use the Madre de Dios River to cross into Bolivia; Special Forces were ready to detain miners on both sides of the border. [12]

- The Swiss government has arranged a purchase of gold from small-scale formal miners in Puno. The Better Gold Initiative is assisting the Swiss government to work with formal mining cooperatives and incentivize the formalization process in the region. [13]

- A report by Public Eye (Ojo-Publico) investigated two Swiss-based companies, MKS and Metalor, which have been linked to buying gold from illegal mines in Peru. In response, the Public Minister of Peru is asking for international judicial aid from the Swiss government to allow the Peruvian government to interrogate representatives from each company.[14]

Economy

- According to a report by the Peruvian Economy Institute (IPE), Madre de Dios region had significant economic growth in the second trimester of 2015, with a growth rate of 29.7%. In comparison, Madre de Dios had an economic growth rate of only 2.4% in the first trimester of 2015. In the report released by the IPE, the significant economic growth correlates with less intense government action against illegal mining, allowing for the recovery of gold production.[15]

- An investigation by the Superintendent of Banks and Insurance estimates that 947 million USD is laundered in order to support illegal gold mining operations, which accounts for at least 5% of the 140 tons of gold produced in Peru in 2014.[16]

- In September, the 32nd annual Perumin Mining Convention will be held in Arequipa, and the issue of the formalization of artisanal miners will be discussed. Discussions will also cover the changing price of gold and its relation to the number of informal miners in the country. The Federation of Artisanal Miners of Arequipa (FEMAR) and a panel of specialists will be there to discuss the problem of illegal mining. [17]

Other

- The Peruvian Society for Environmental Rights (SPDA) released an investigation of illegal gold mining in five South American countries titled “The routes of illegal gold. Case studies in five Amazon countries.” The Peruvian section analyzes the politics around resource access and the sprawl of illegal mining territory; particularly, the fact that from 2000 to 2009, there were 1,548 requests for mining rights in Peru, surpassing all other land rights requests. [18]

- Two officers died and three collapsed during an operation against illegal mining in Madre de Dios. The officers suffered from dehydration due to the intense heat, and an investigation is being conducted by the Ombudsman to see if there was any negligence. [19] [20]

- The declaration of mining activity in the Condor mountain range has created conflict with the Awajún-wampis community in the Amazon region. They have not permitted the development of mining camps in the headwaters of their water source and that plans were made behind their backs, violating the law. The Awajun-wampis also warned that they are organizing a large assembly in the Shaim community to determine how to defend the Condor mountain range, including the formation of the Ichigkat Muja National Park. [21]

Notes: The ACA Mining News Watch focuses mostly on issues pertaining to the Peruvian Amazon and may not cover issues related to non-Amazonian parts of the country. We would like to credit ProNaturaleza’s “Observatorio Amazonia” as our primary resource for articles related to illegal mining in Peru.

Photo Credit: http://elcomercio.pe/peru/madre-de-dios/operacion-contra-mineria-ilegal-pampa-fotos-noticia-1826310/3

ACA contact for Comments/Questions: Sarah Feder (sfeder@amazonconservation.org) and Matt Finer (mfiner@amazonconservation.org)

Citation: DeRycke E, Feder S, Finer M (2015). Peru Mining News Watch Report #18. Amazon Conservation Association. https://www.maapprogram.org/2015/08/mining-news-watch-18