We present our second synthesis report, building off our first report published in September 2015. This synthesis is largely based on the 50 MAAP reports published between April 2015 and November 2016. The objective is to synthesize all the information to date regarding deforestation trends, patterns and drivers in the Peruvian Amazon.

MAAP methodology includes 4 major components: Forest loss detection, Prioritize big data, Identify deforestation drivers, and Publish user-friendly reports. See Methodology section below for more details.

Our major findings include:

- Trends. During the 15 years between 2001 and 2015, around 4,448,000 acres (1,800,000 hectares) of Peruvian Amazon forest has been cleared, with a steadily increasing trend. 2014 had the highest annual forest loss on record (438,775 acres), followed by a slight decrease in 2015. The preliminary estimate for 2016 indicates that forest loss remains relatively high. The vast majority (80%) of forest loss events in the Peruvian Amazon are small-scale (<5 hectares), while large-scale events (> 50 hectares) pose a latent threat due to new agro-industrial projects.

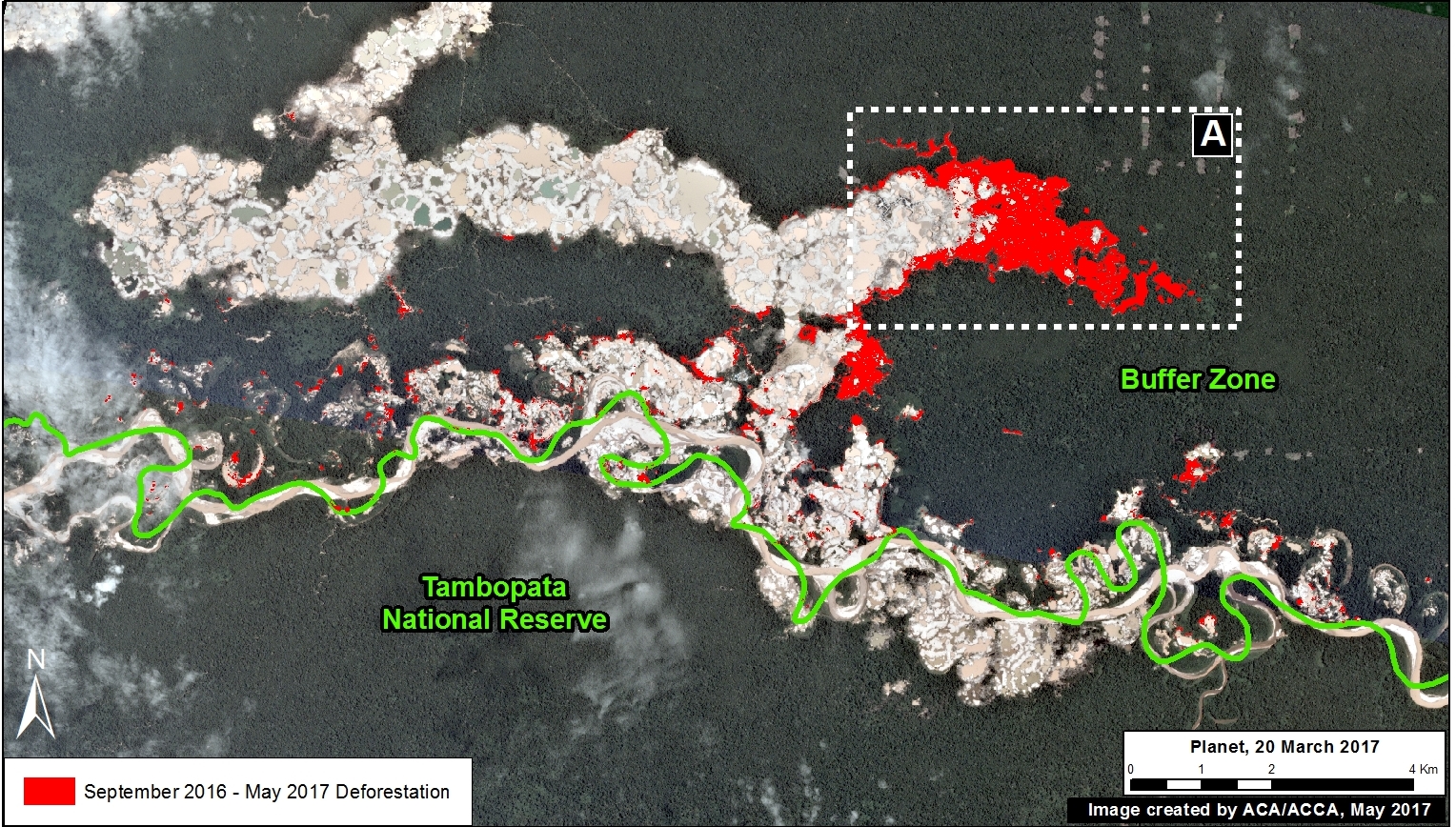

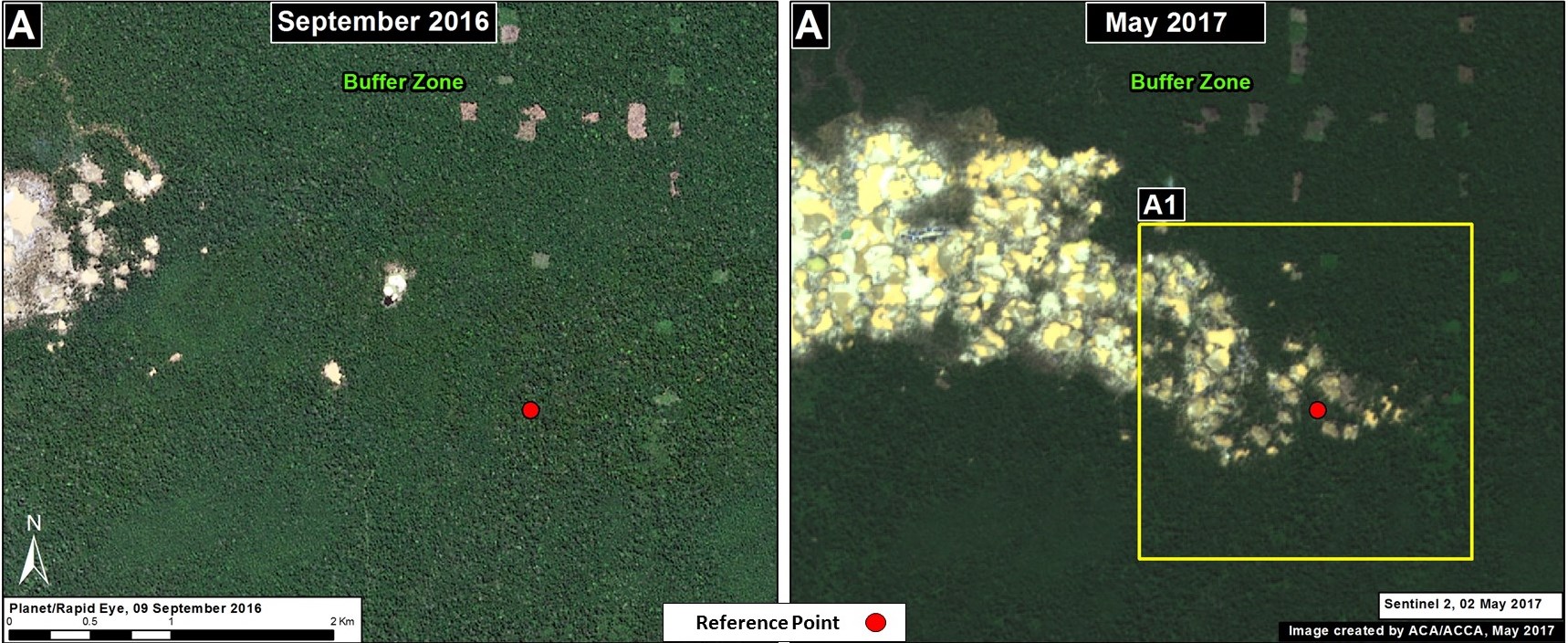

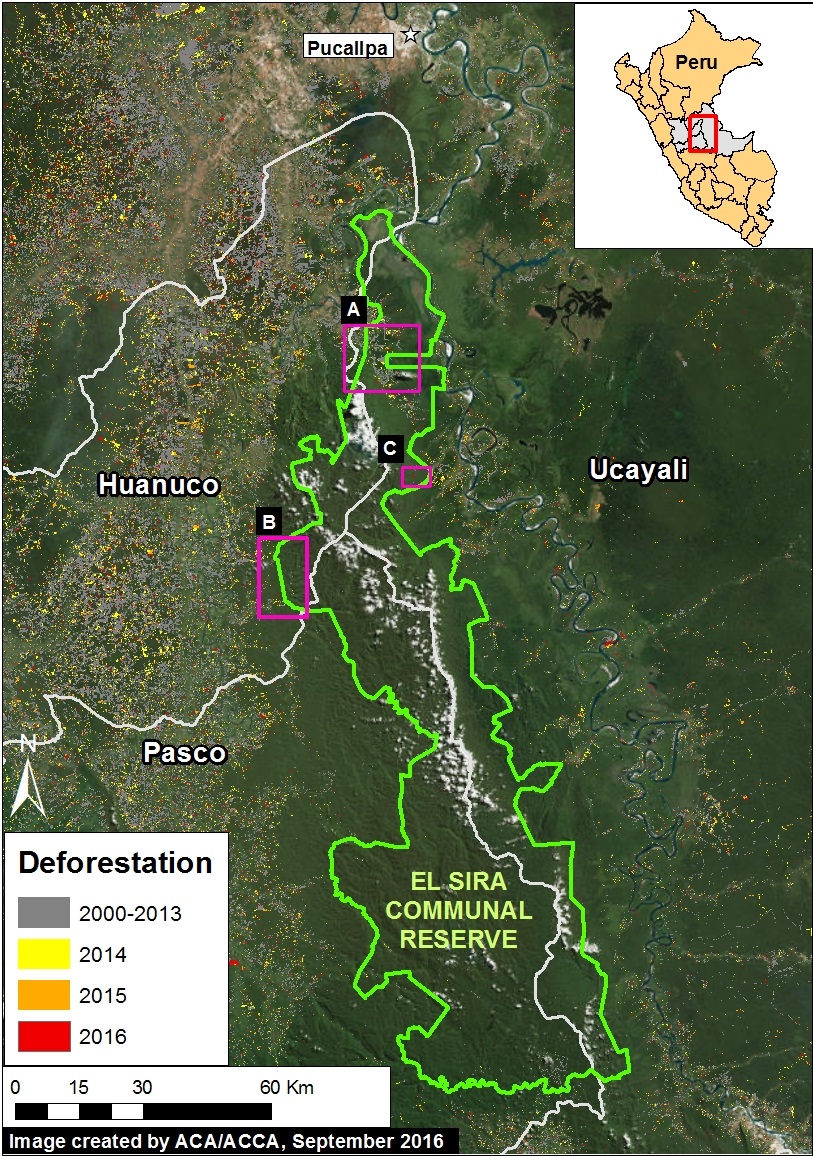

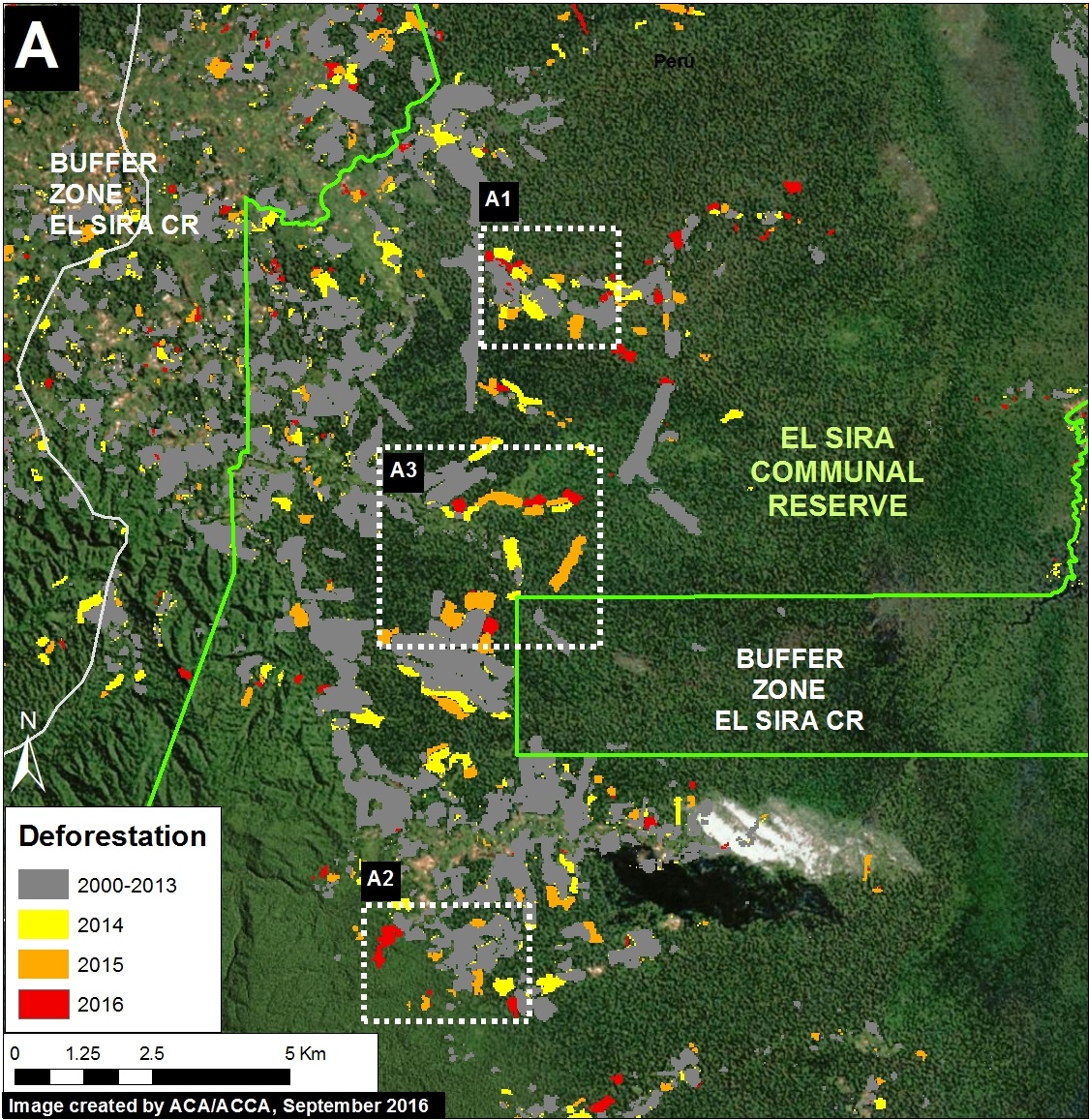

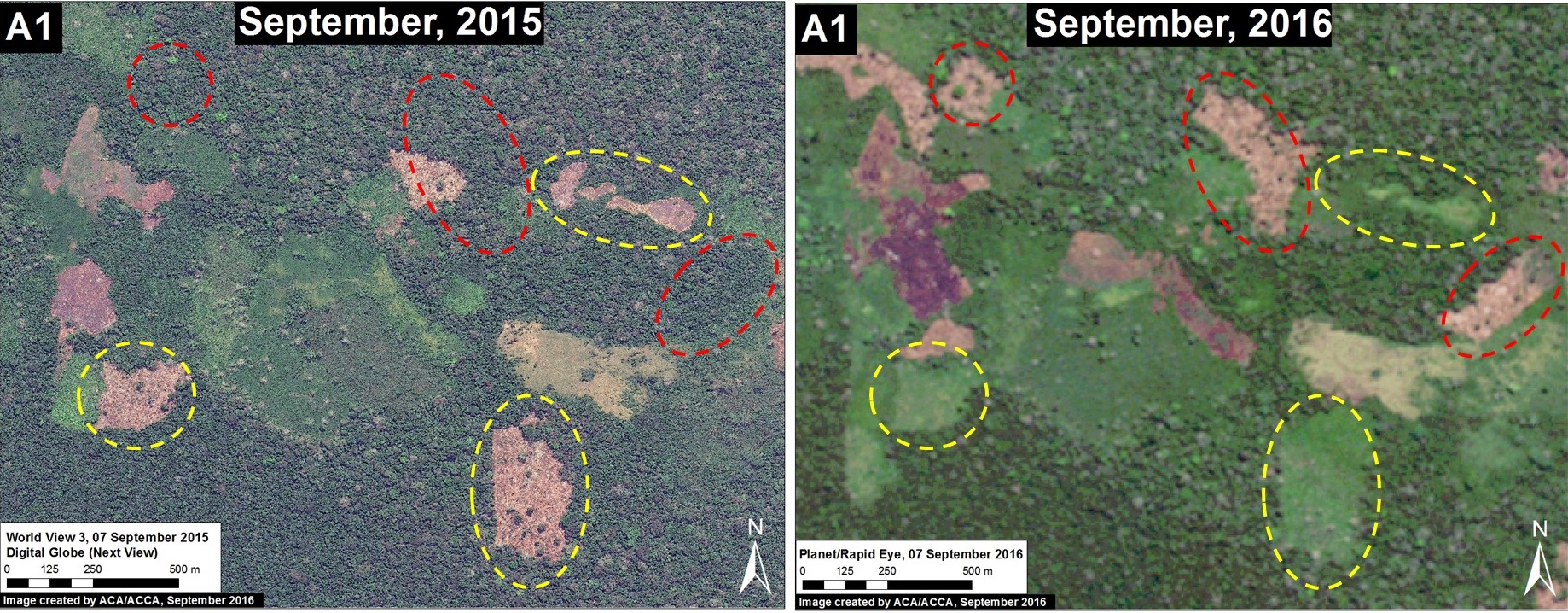

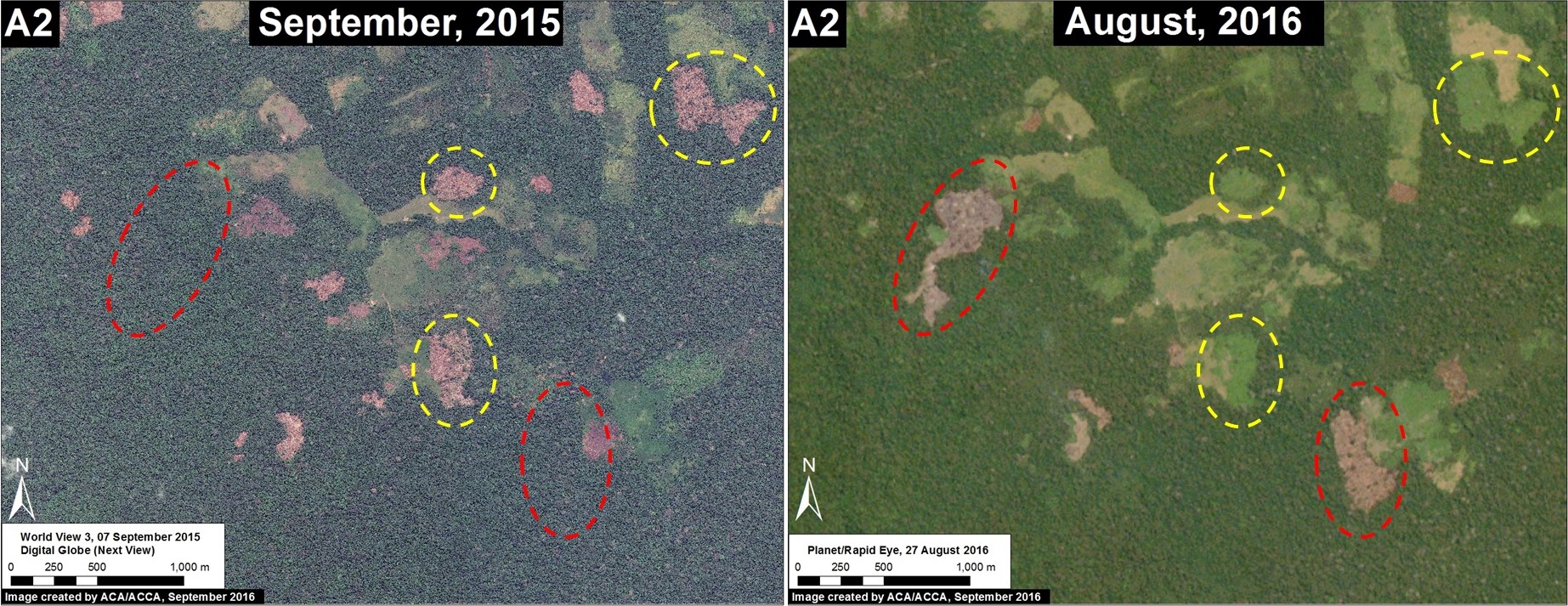

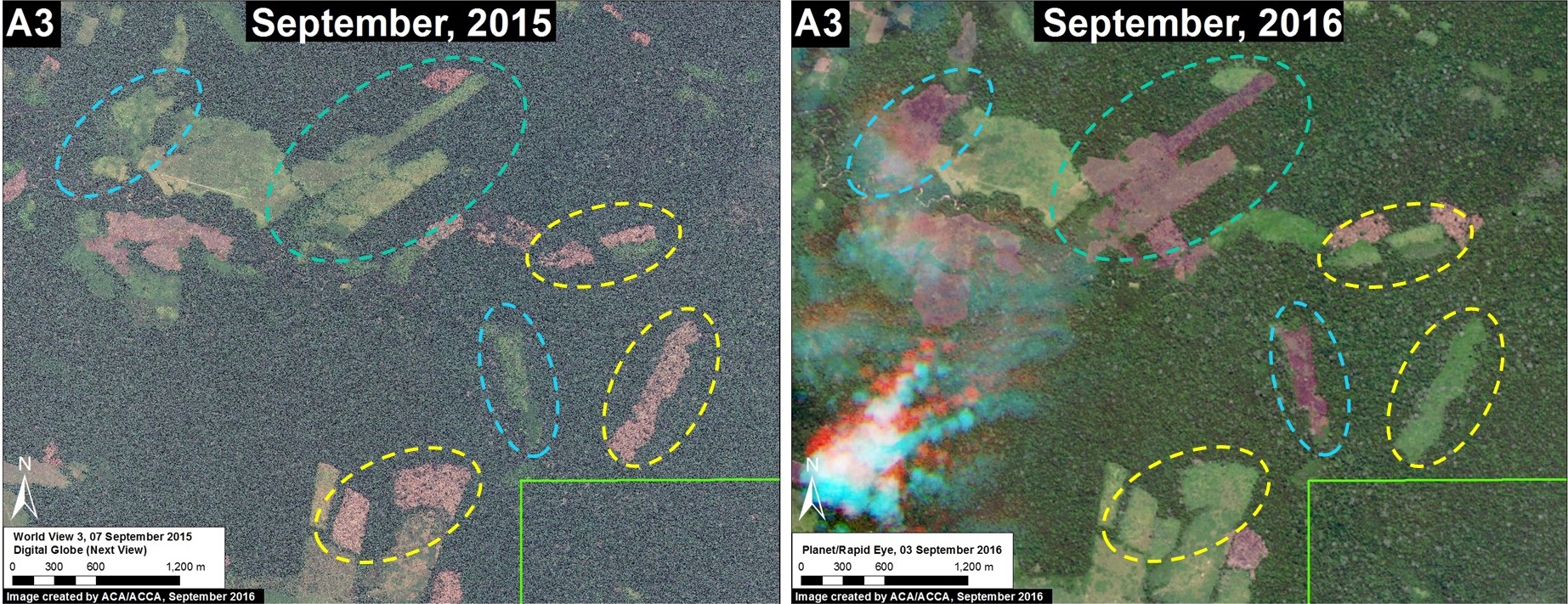

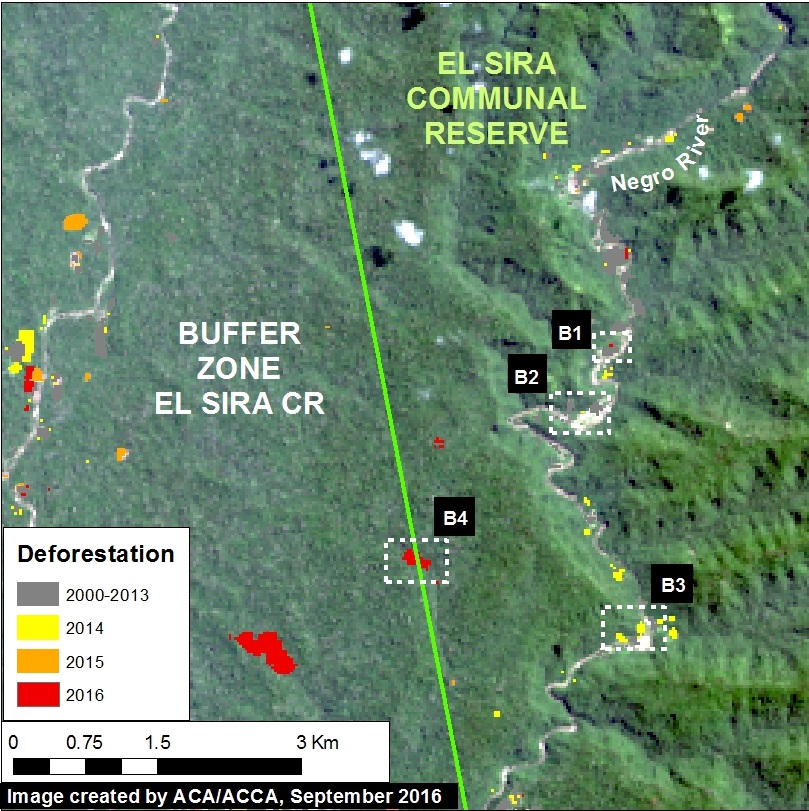

- Hotspots. We have identified at least 8 major deforestation hotspots. The most intense hotspots are located in the central Amazon (Huánuco and Ucayali). Other important hotspots are located in Madre de Dios and San Martin. Two protected areas (Tambopata National Reserve and El Sira Communal Reserve) are threatened by these hotspots.

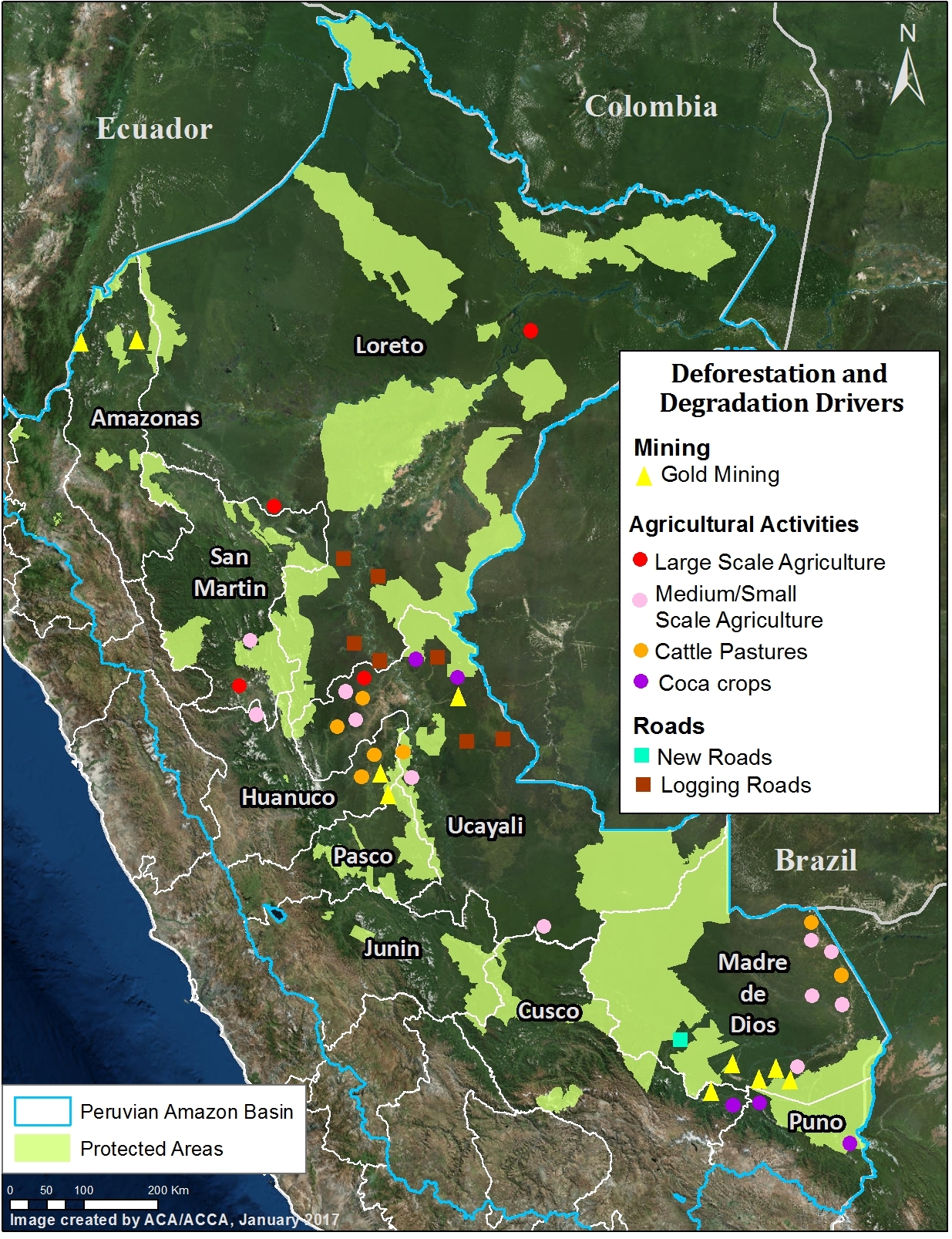

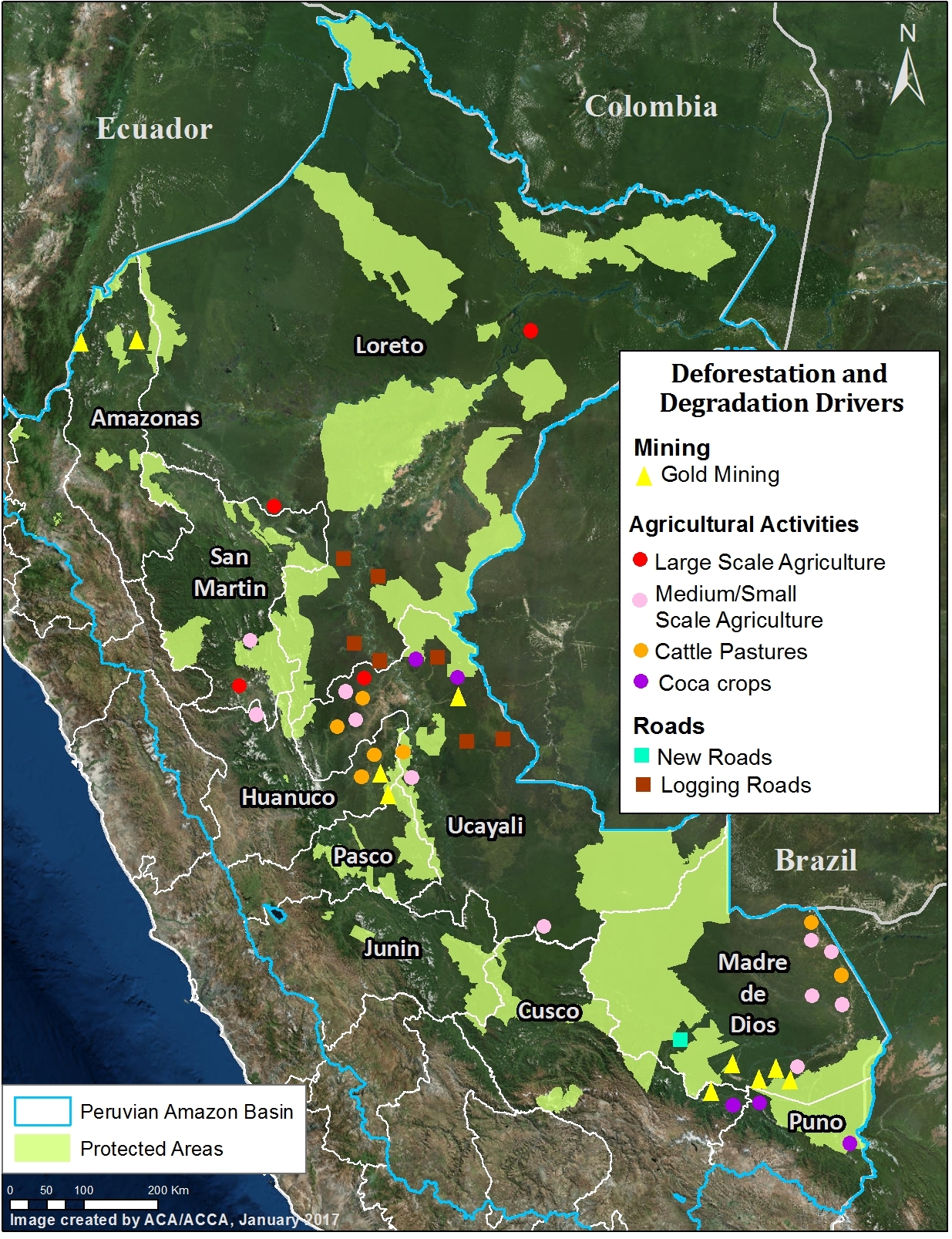

- Drivers. We present an initial deforestation drivers map for the Peruvian Amazon. Analyzing high-resolution satellite imagery, we have documented six major drivers of deforestation and degradation: small/medium-scale agriculture, large-scale agriculture, cattle pasture, gold mining, illegal coca cultivation, and roads. Small-scale agriculture and cattle pasture are likely the most dominant drivers overall. Gold mining is a major driver in southern Peru. Large-scale agriculture and major new roads are latent threats. Logging roads are likely a major source of forest degradation in central Peru.

Deforestation Trends

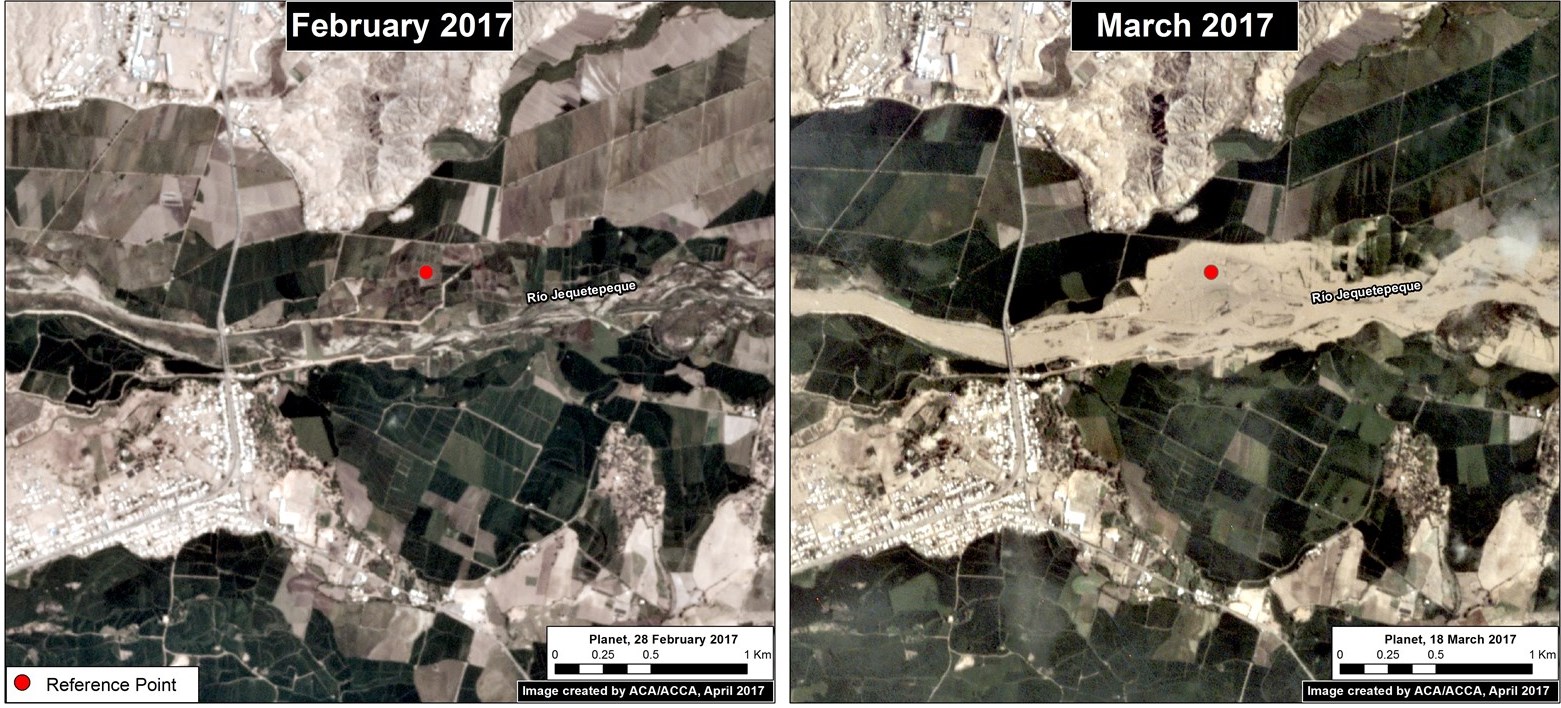

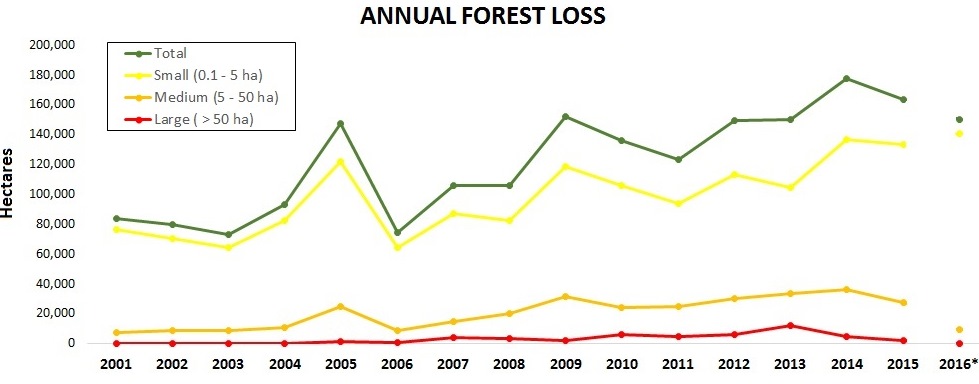

Image 1 shows forest loss trends in the Peruvian Amazon from 2001 to 2015, including a breakdown of the size of the forest loss events. This includes the official data from the Peruvian Environment Ministry, except for 2016, which is a preliminary estimate based on GLAD forest loss alerts.

Image 1. Data: PNCB/MINAM, UMD/GLAD. *Estimate based on GLAD alerts.

During the 15 years between 2001 and 2015, around 4,448,000 acres (1,800,000 hectares) of Peruvian Amazon forest has been cleared (see green line). This represents a loss of approximately 2.5% of the existing forest as of 2001.There have been peaks in 2005, 2009, and 2014, with an overall increasing trend. In fact, 2014 had the highest annual forest loss on record (386,626 acres). Forest loss decreased in 2015 (386,732 acres), but is still the second highest recorded. The preliminary estimate for 2016 indicates that forest loss continues to be relatively high.

It is important to note that the data include natural forest loss events (such as storms, landslides, and river meanders), but overall serves as our best proxy for anthropogenic deforestation. The non-anthropogenic forest loss is estimated to be approximately 3.5% of the total.1

The vast majority (81%) of forest loss events in the Peruvian Amazon are small-scale (<5 hectares, equivalent of 12 acres), see the yellow line. Around 16% of the forest loss events are medium-scale (5-50 hectares, equivalent of 12-124 acres), see the orange line. Large-scale (>50 hectares, equivalent of 124 acres) forest loss events, often associated with industrial agriculture, pose a latent threat. Although the average is only 2%, large-scale forest loss rapidly spiked to 8% in 2013 due to activities linked with a pair of new oil palm and cacao plantations. See MAAP #32 for more details on the patterns of sizes of deforestation events.

Deforestation Patterns

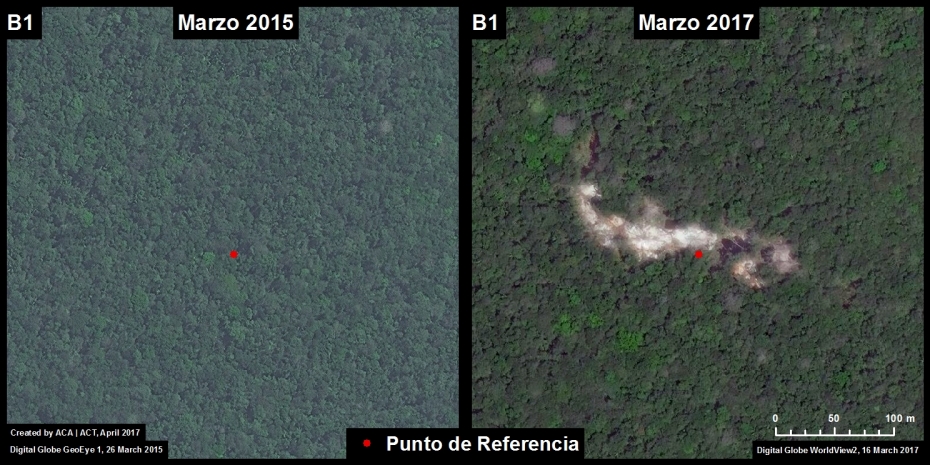

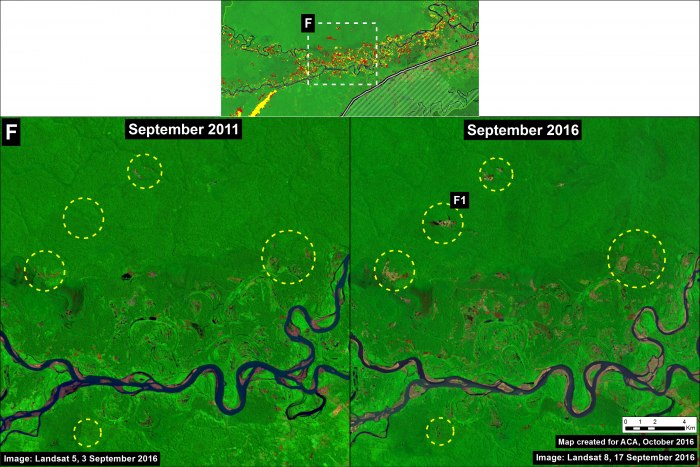

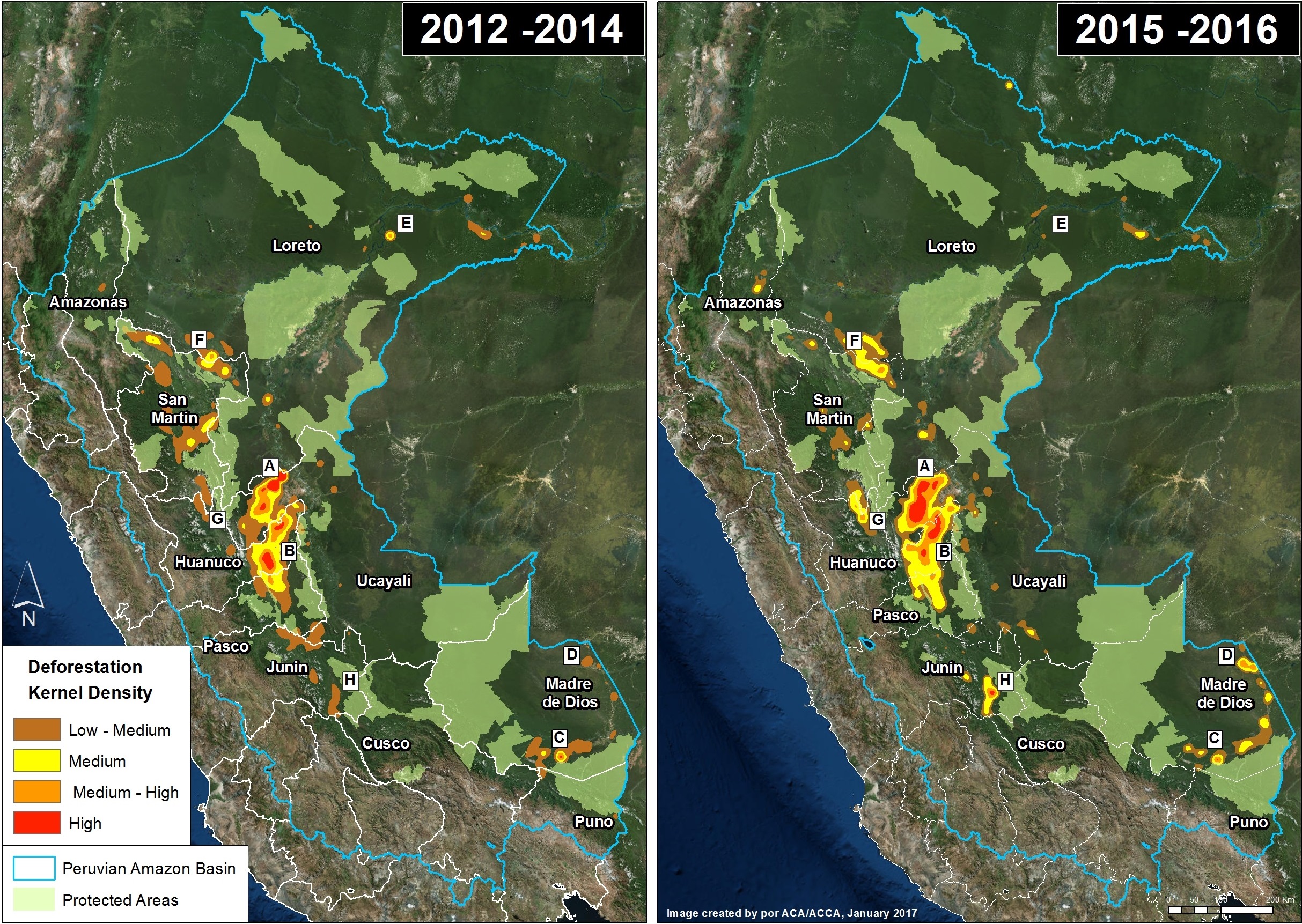

Image 2 shows the major deforestation hotspots in 2012-14 (left panel) relative to 2015-16 (right panel), based on a kernel density analysis.2 We have identified at least 8 major deforestation hotspots, labeled as Hotspots A-H.

Image 2. Data: PNCB/MINAM, GLAD/UMD. Click to enlarge.

The most intense hotspots, A and B, are located in the central Amazon. Hotspot A, in northwest Ucayali, was dominated by two large-scale oil palm projects in 2012-14, but then shifted a bit to the west in 2015-16, where it was dominated by cattle pasture and small-scale oil palm. Hotspot B, in eastern Huánuco, is dominated by cattle pasture (MAAP #26).

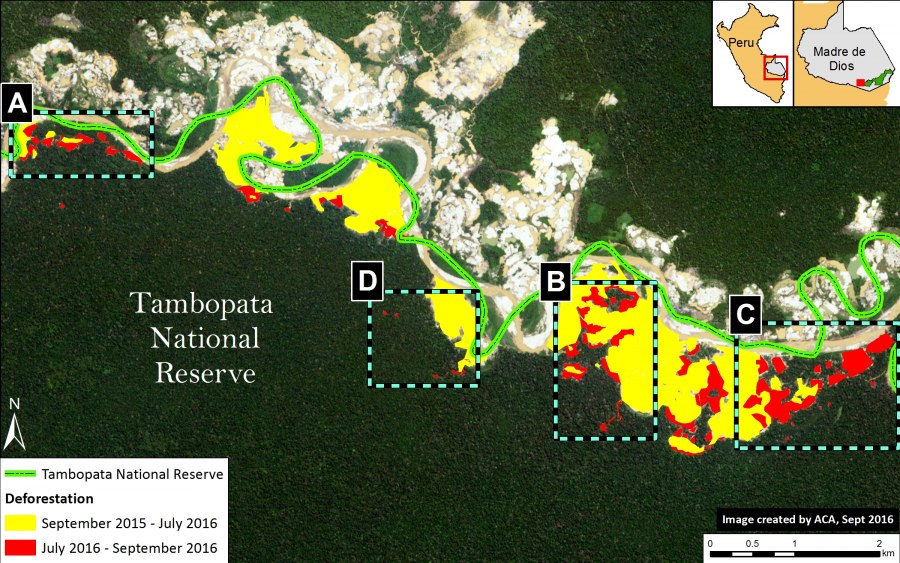

Hotspots C and D are in the Madre de Dios region in the southern Amazon. Hotspot C indicates the primary illegal gold mining front in recent years (MAAP #50). Hotspot D highlights the emerging deforestation zone along the Interoceanic Highway, particularly around the town of Iberia (MAAP #28).

Hotspots E-H are agriculture related. Hotspot E indicates the rapid deforestation for a large-scale cacao plantation in 2013-14, with a sharp decrease in forest loss 2015-16 (MAAP #35). Hotspot F indicates the expanding deforestation around two large-scale oil palm plantation (MAAP #41). Hotspot G indicates the intensifying deforestation for small-scale oil palm plantations (MAAP #48).

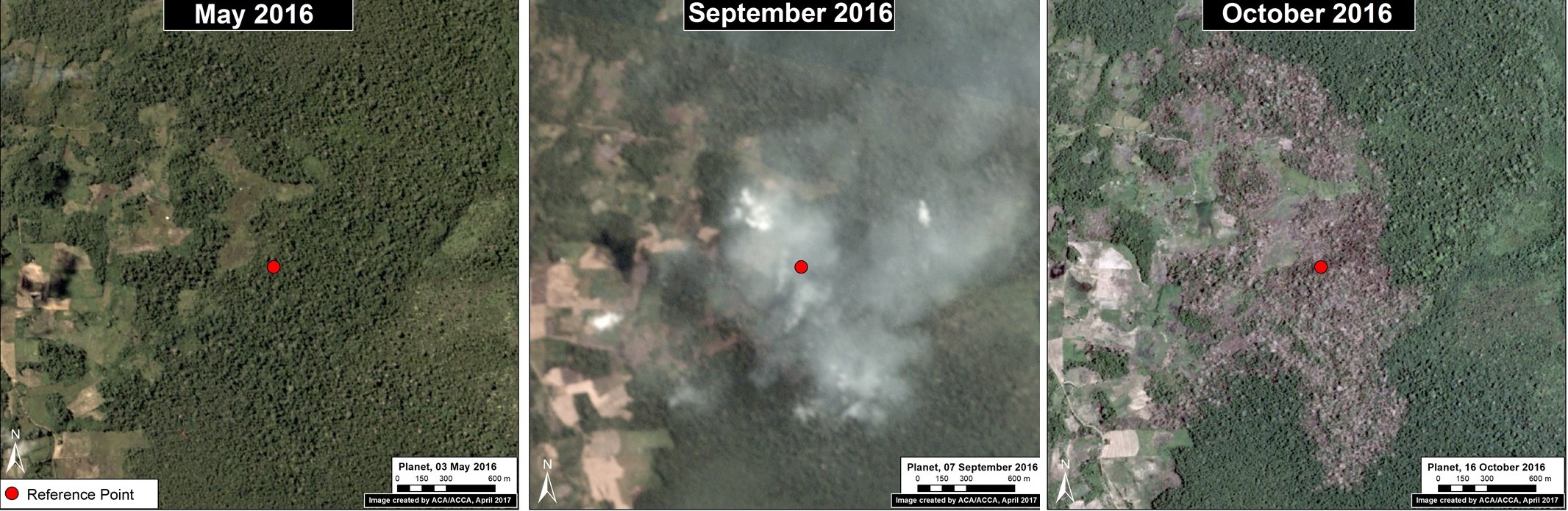

Hotspot H indicates an area impacted by intense wildfires in 2016.

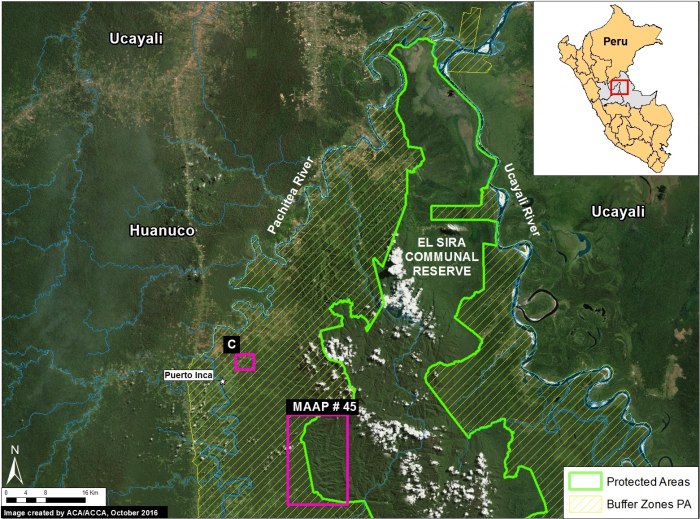

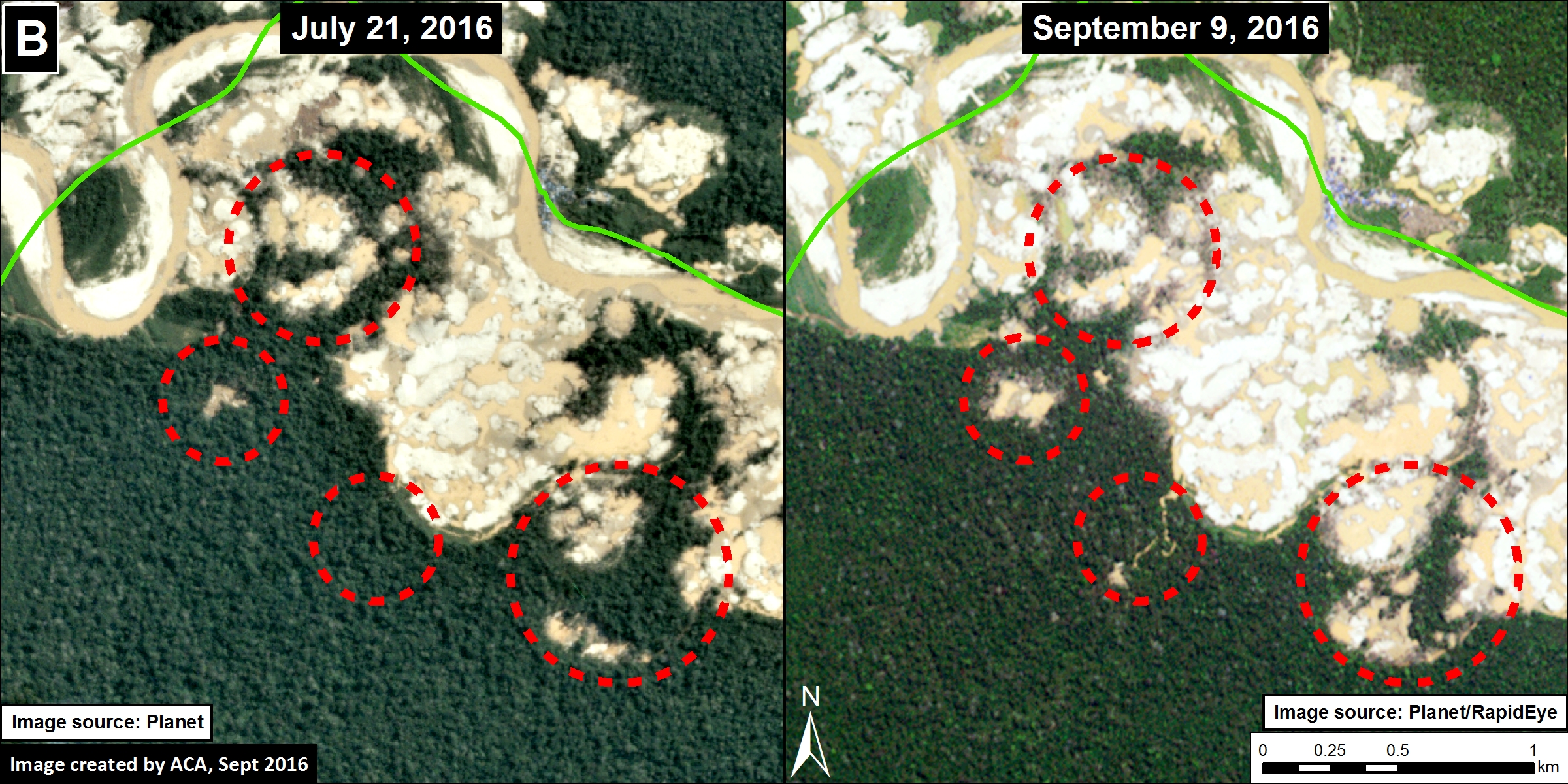

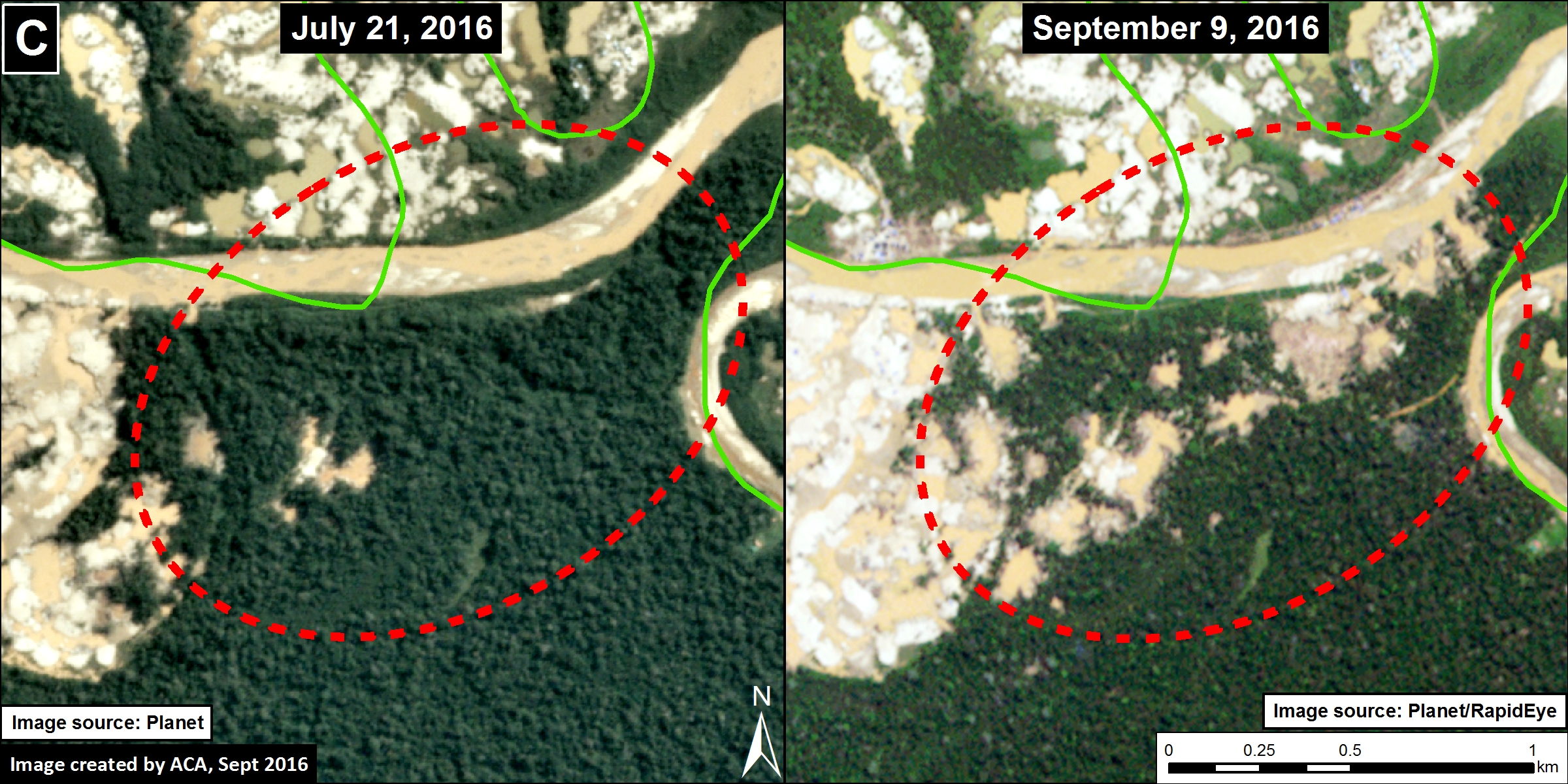

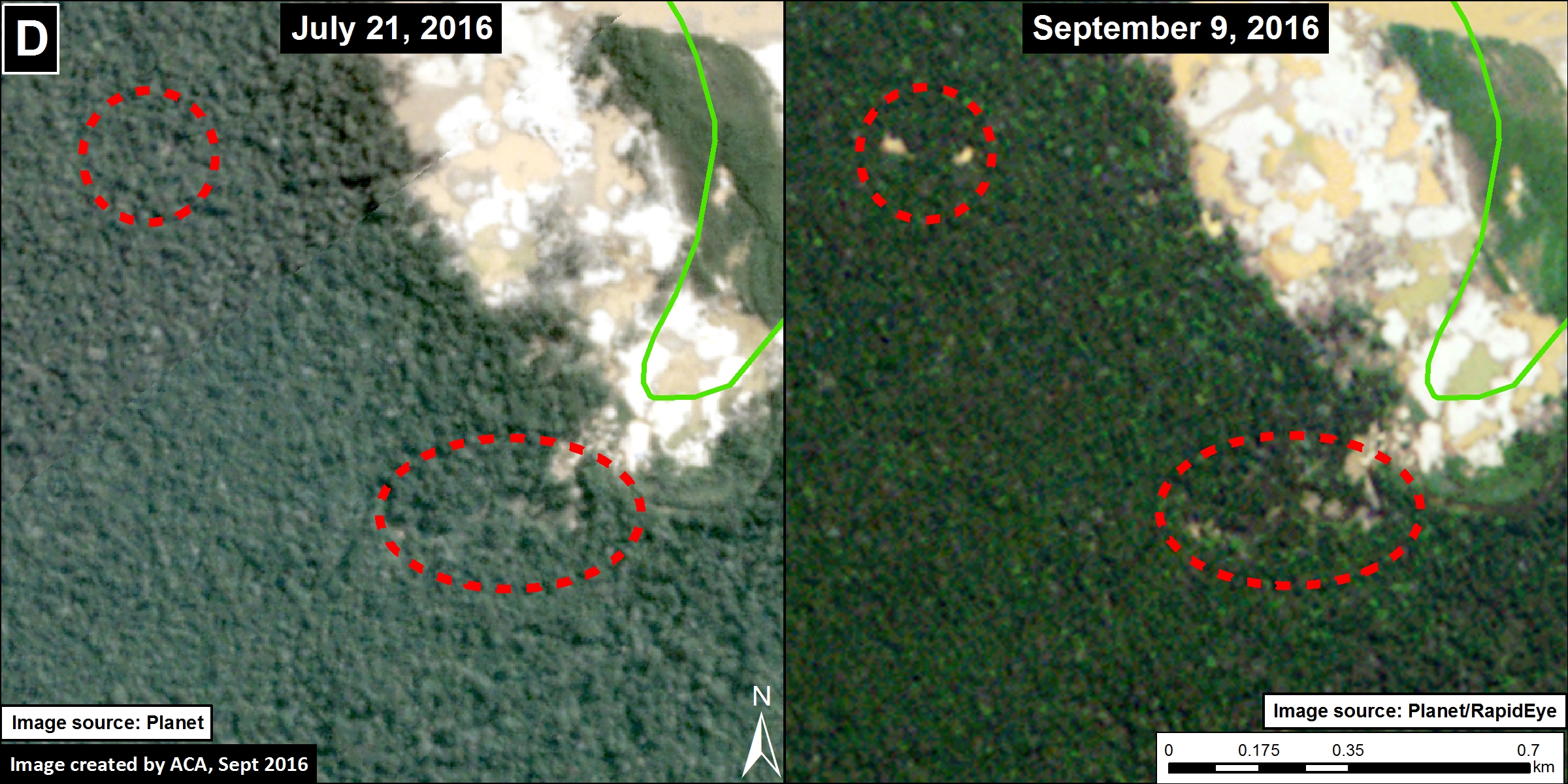

Protected Areas, in general, are effective barriers against deforestation (MAAP #11). However, several protected areas are currently threatened, most notably Tambopata National Reserve (Hotspot C; MAAP #46). and El Sira Communal Reserve (Hotspot B; MAAP #45).

Deforestation Drivers

Image 3. Data: MAAP, SERNANP. Click to enlarge.

Surprisingly, there is a striking lack of precise information about the actual drivers of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. According to an important paper published in 2016, much of the existing information is vague and outdated, and is based solely on a general analysis of the size of deforestation events.3

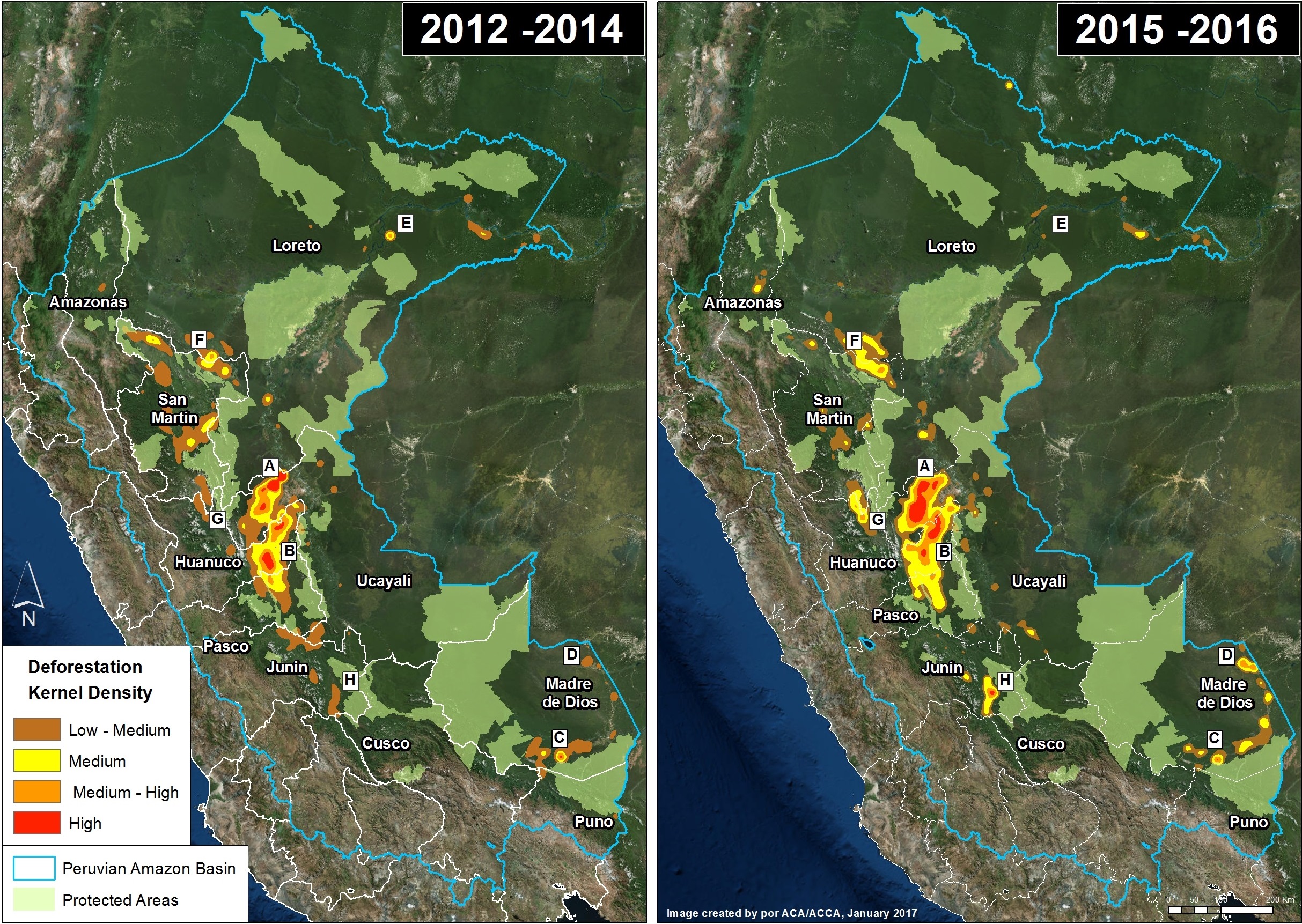

As noted above, one of the major advances of MAAP has been using high-resolution imagery to better identify deforestation drivers.

Image 3 shows the major deforestation drivers identified thus far by our analysis. As far as we know, it represents the first spatially explicit deforestation drivers map for the Peruvian Amazon.

To date, we have documented six major direct drivers of deforestation and degradation in the Peruvian Amazon: small/medium-scale agriculture, large-scale agriculture, cattle pasture, gold mining, illegal coca cultivation, and roads.

At the moment, we do not consider the hydrocarbon (oil and gas) and hydroelectric dam sectors as major drivers in Peru, but this could change in the future if proposed projects move forward.

We describe these major drivers of deforestation and degradation in greater detail below.

Small/Medium-scale Agriculture

The literature emphasizes that small-scale agriculture is the leading cause of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon.1 However, there is little actual empirical evidence demonstrating that this is true.3 The raw deforestation data is dominated by small-scale clearings that are most likely for agriculture or cattle pasture. Thus, it is likely that small-scale agriculture is a major driver, but a definitive study utilizing high-resolution imagery and/or extensive field work is still needed to verify the assumption.

In several key case studies, we have shown specific examples of small-scale agriculture being a deforestation driver. For example, using a combination of high-resolution imagery, photos from the field, and local sources, we have determined that:

- Oil Palm, in the form of small and medium-scale plantations, is one of the main drivers within deforestation Hotspot B (Ucayali; MAAP #26), Hotspot G (northern Huánuco; MAAP #48), and Hotspot F (Loreto-San Martin;MAAP #16). This was also shown for Ucayali in a recent peer-reviewed study.4 See below for information about large-scale oil palm.

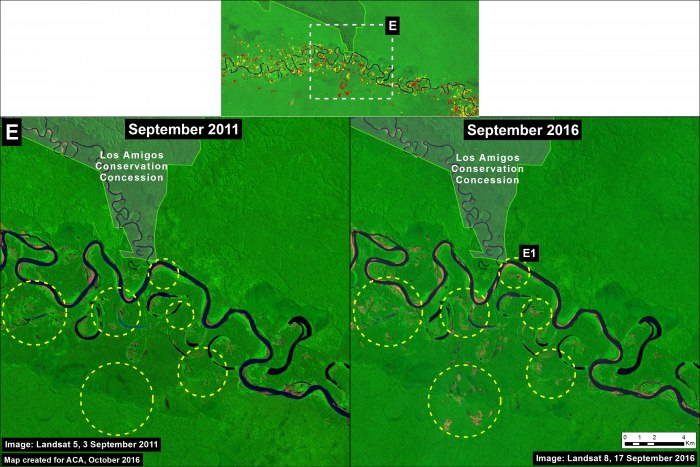

- Cacao is causing rapid deforestation along the Las Piedras River in eastern Madre de Dios (MAAP #23, MAAP #40). See below for information about large-scale cacao.

- Papaya is an important new driver in Hotspot D, along the Interoceanic Higway in eastern Madre de Dios (MAAP #42).

- Corn and rice plantations may also be an important driver in Hotspot D in eastern Madre de Dios (MAAP #28).

Large-scale Agriculture

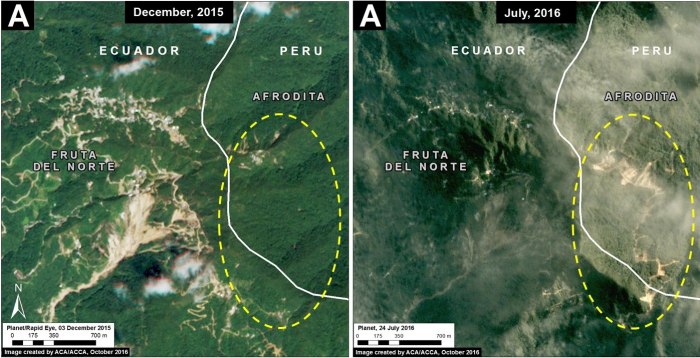

Large-scale, agro-industrial deforestation remains a latent threat in Peru, particularly in the central and northern Amazon regions. This issue was put on high alert in 2013, with two cases of large-scale deforestation for oil palm and cacao plantations, respectively.

In the oil palm case, two companies that are part of the Melka group,5 cleared nearly 29,650 acres in Hotspot A in Ucayali between 2012 and 2015 (MAAP #4, MAAP #41). In the cacao case, another company in the Melka group (United Cacao) cleared 5,880 acres in Hotspot E in Loreto between 2013 and 2015 (MAAP #9, MAAP #13, MAAP #27, MAAP #35). Dennis Melka has explicitly stated that his goal is to bring the agro-industrial production model common in Southeast Asia to the Peruvian Amazon.6

Prior to these cases, large-scale agricultural deforestation occurred between 2007 and 2011, when oil palm companies owned by Grupo Palmas7 cleared nearly 17,300 acres for plantations in Hotspot H along the Loreto-San Martin border (MAAP #16). Importantly, we documented the additional deforestation of 24,215 acres for oil palm plantations surrounding the Grupo Palmas projects (MAAP #16).

In contrast, large-scale agricultural deforestation was minimal in 2015 and 2016. However, as noted above, it remains a latent threat. Both United Cacao and Grupo Palmas have expansion plans that would clear over 49,420 acres of primary forest in Loreto.8

Cattle Pasture

Using an archive of satellite imagery, we documented that deforestation for cattle pasture is a major issue in the central Peruvian Amazon. Immediately following a deforestation event, the scene of hundreds or thousands of recently cut trees often looks the same whether the cause is agriculture or cattle pasture. However, by using an archive of imagery and studying deforestation events from previous years, one can more easily determine the drivers of the forest loss. For example, after a year or two, agriculture and cattle pasture appear very differently in the imagery and thus it is possible to distinguish these two drivers.

Using this technique, we determined that cattle pasture is a major driver in Hotspots A and B, in the central Peruvian Amazon (MAAP #26, MAAP #37).

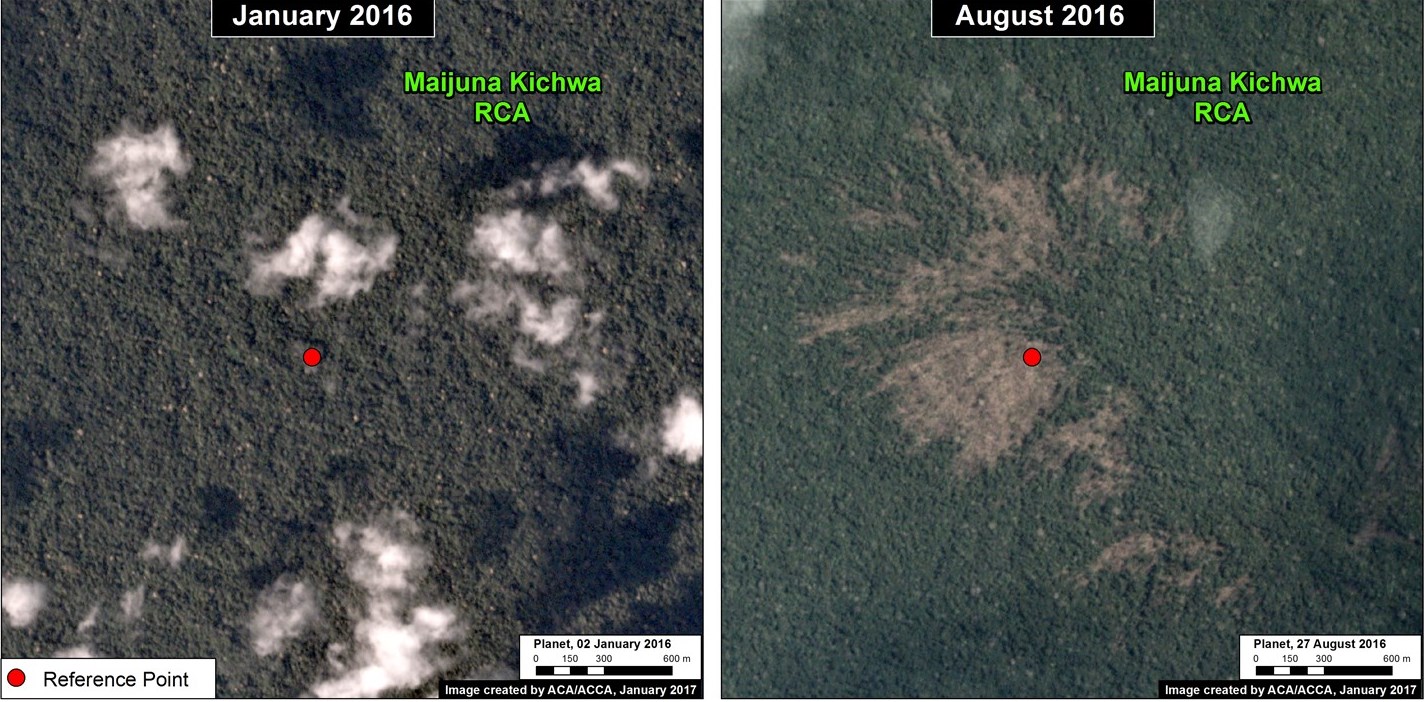

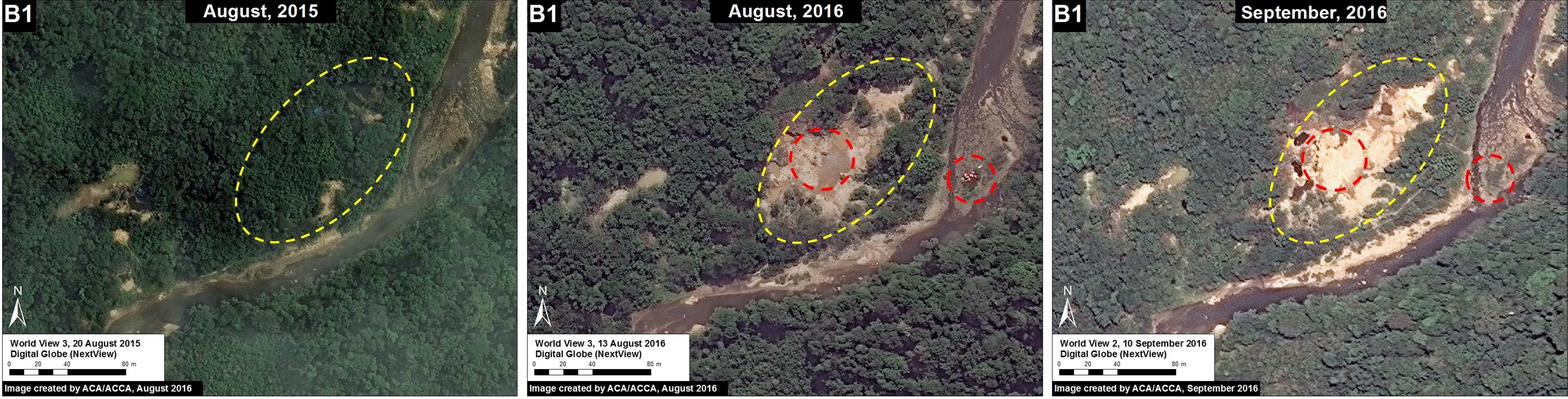

We also used this technique to determine that much of the deforestation in the northern section of El Sira Communal Reserve is due to cattle pasture (MAAP #45).

Maintenance of cattle pasture, and small-scale agriculture, are likely important factors behind the escaped fires that degrade the Amazon during intense dry seasons (MAAP #45, MAAP #47).

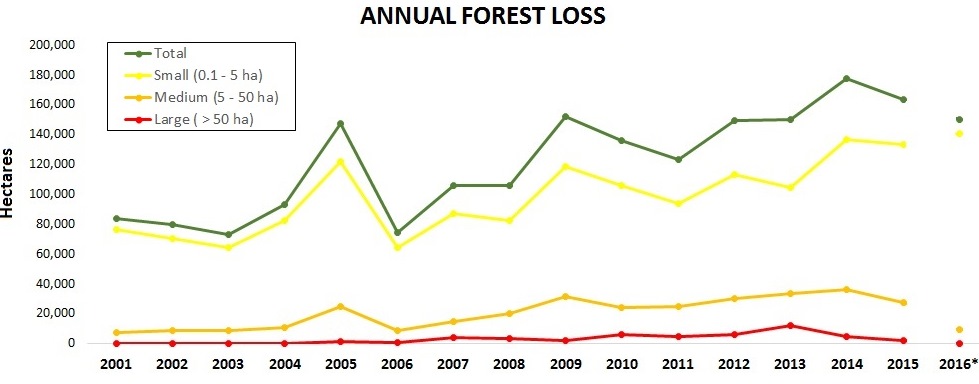

Gold Mining

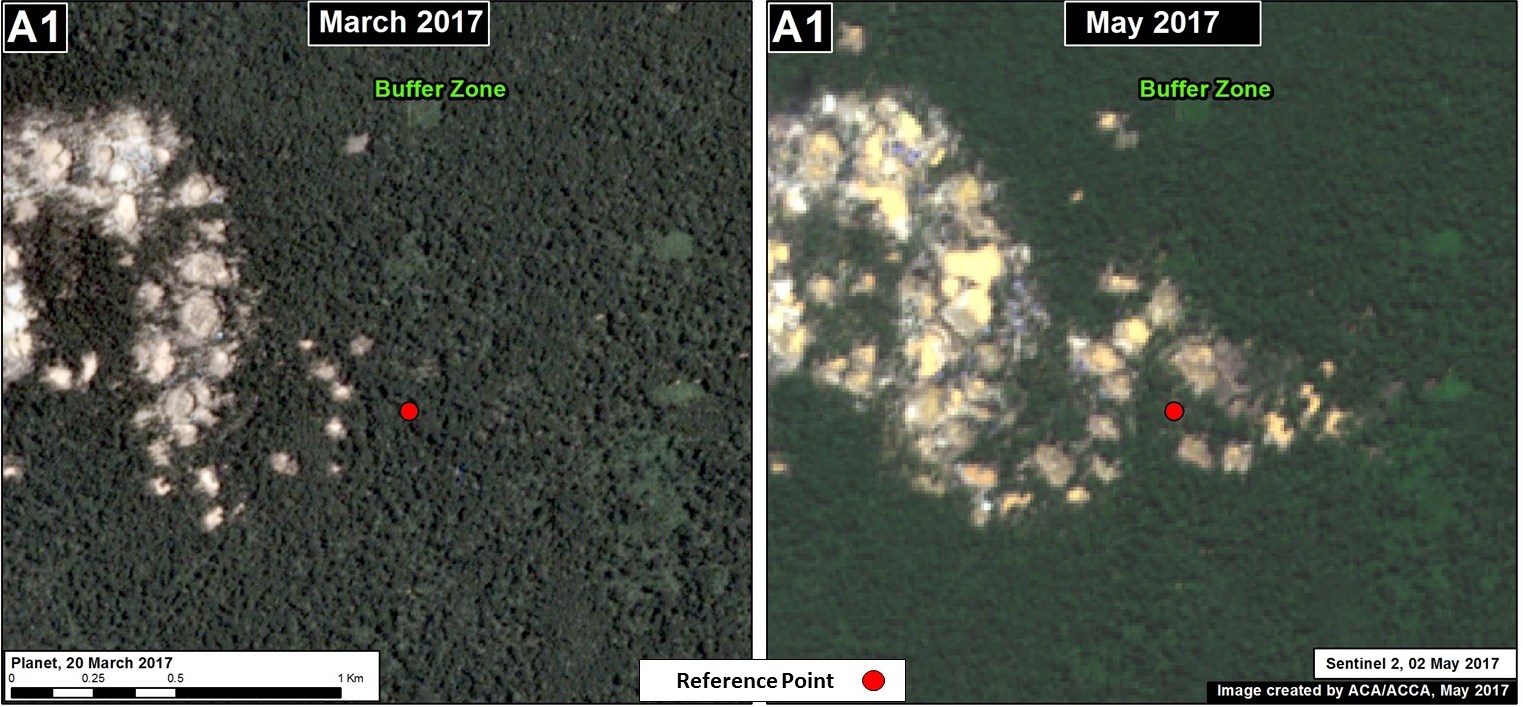

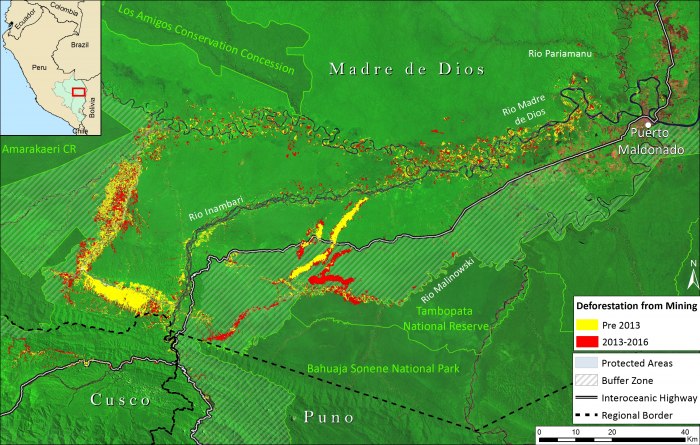

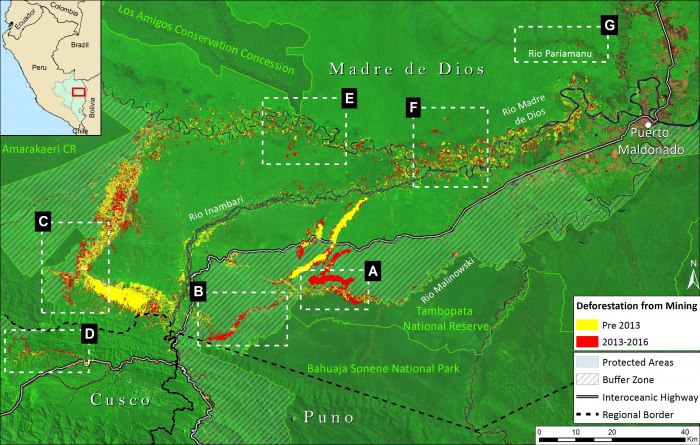

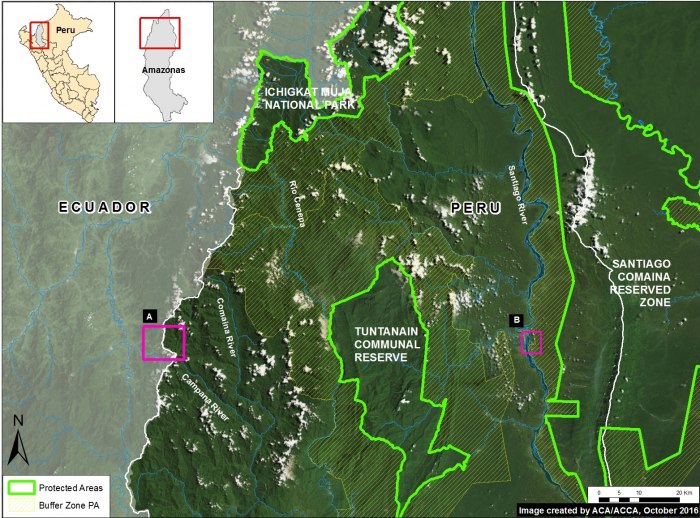

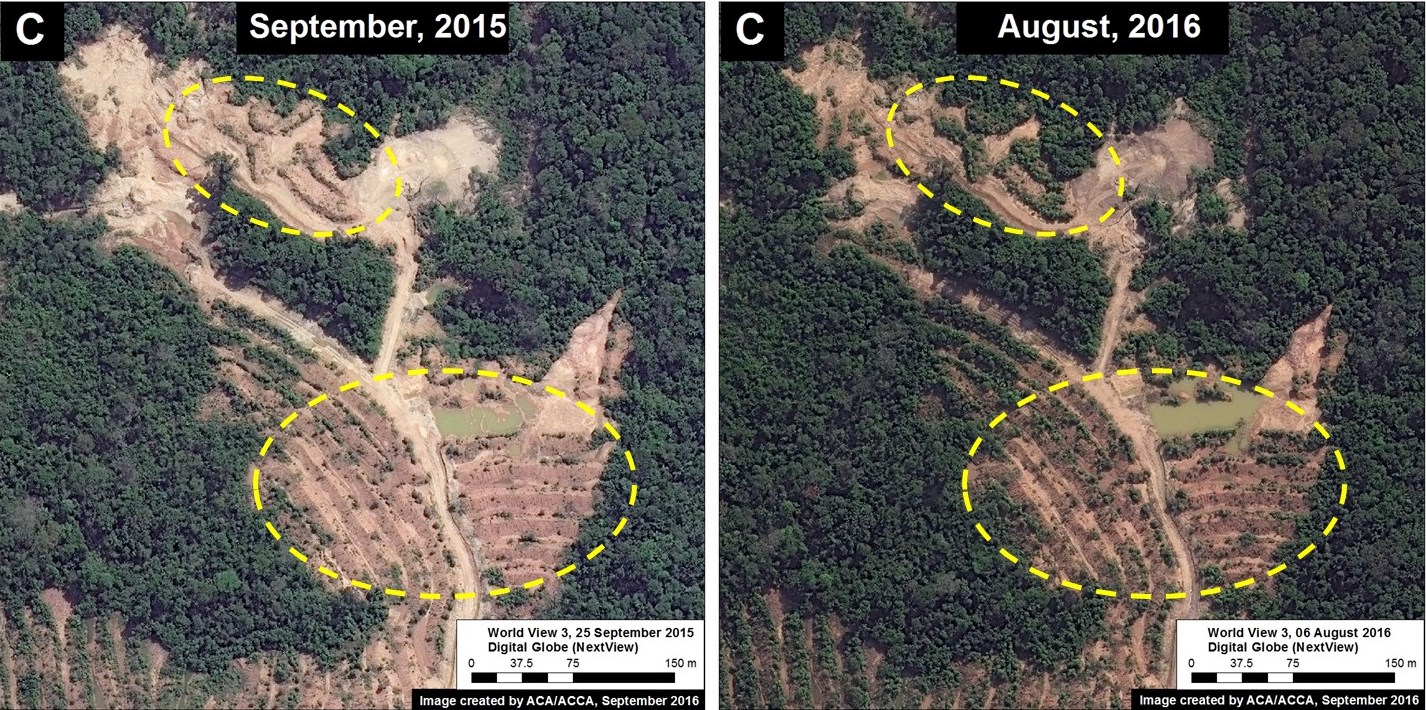

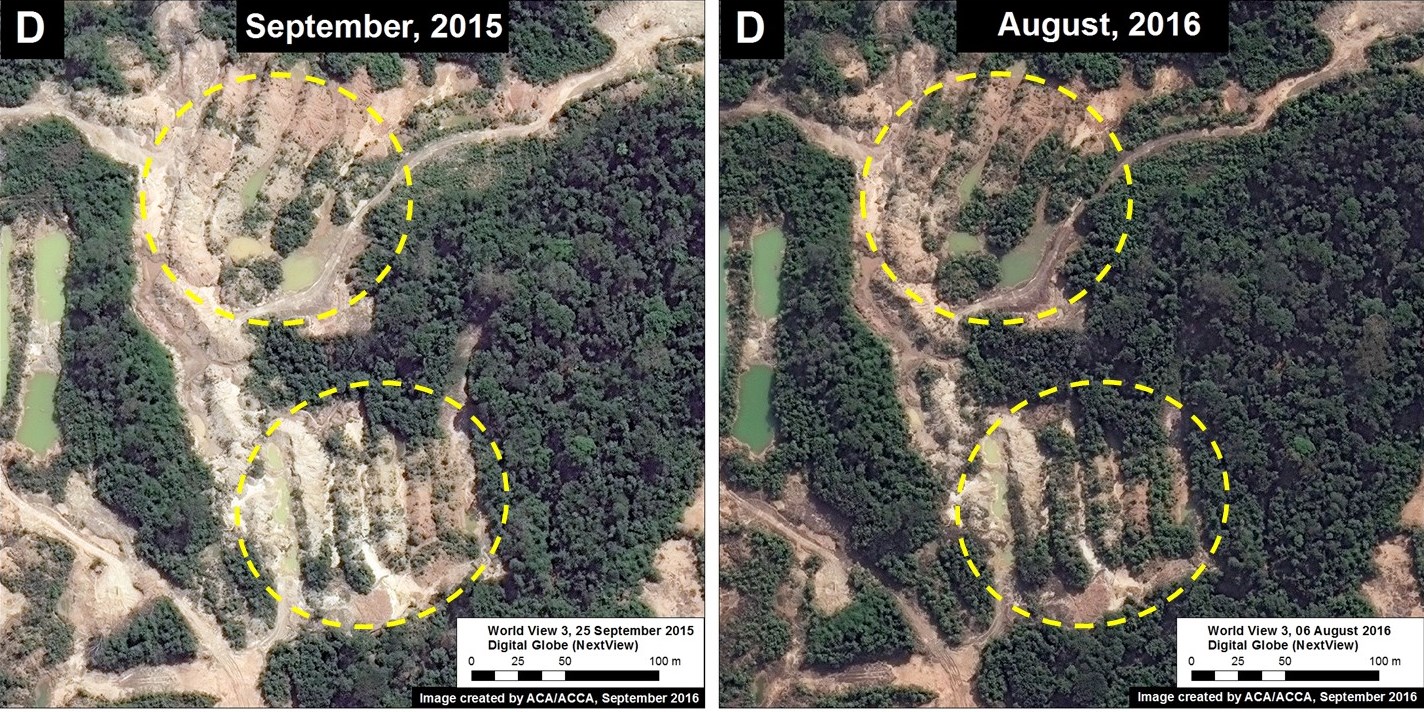

Gold mining is one of the major drivers of deforestation in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Hotspot C). An important study found that gold mining cleared around 123,550 acres up through 2012.9 We built off this work, and by analyzing hundreds of high resolution imageres, found that gold mining caused the loss of an additional 30,890 acres between 2013 and 2016 (MAAP #50). Thus, gold mining is thus far responsible for the total loss of around 154,440 acres in southern Peru. Much of the most recent deforestation is illegal due to its occurrence in protected areas and buffer zones strictly off-limits to mining activities.

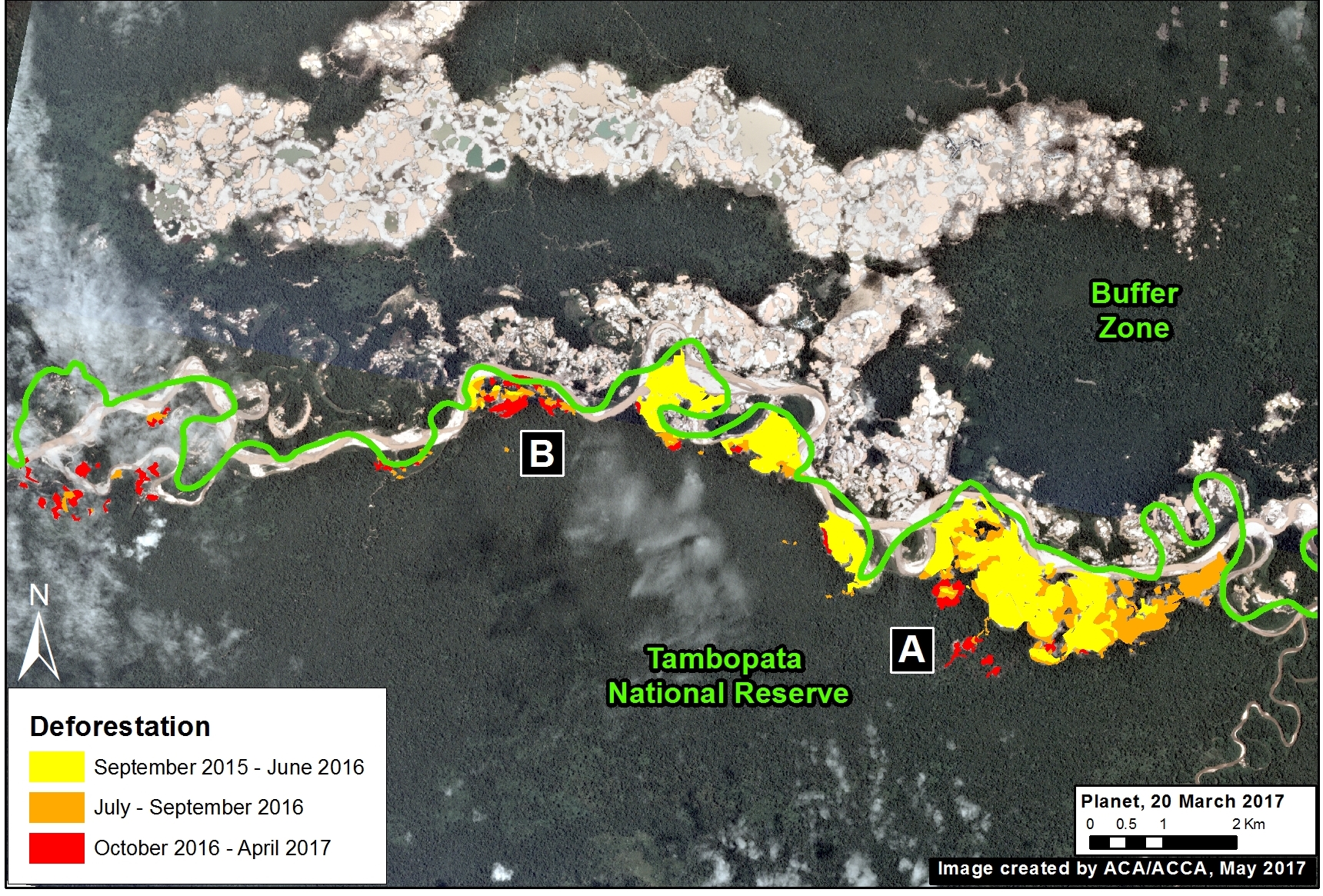

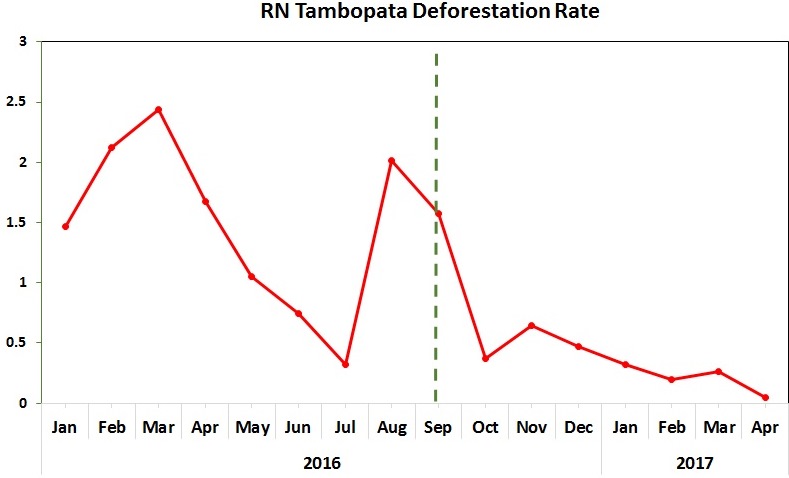

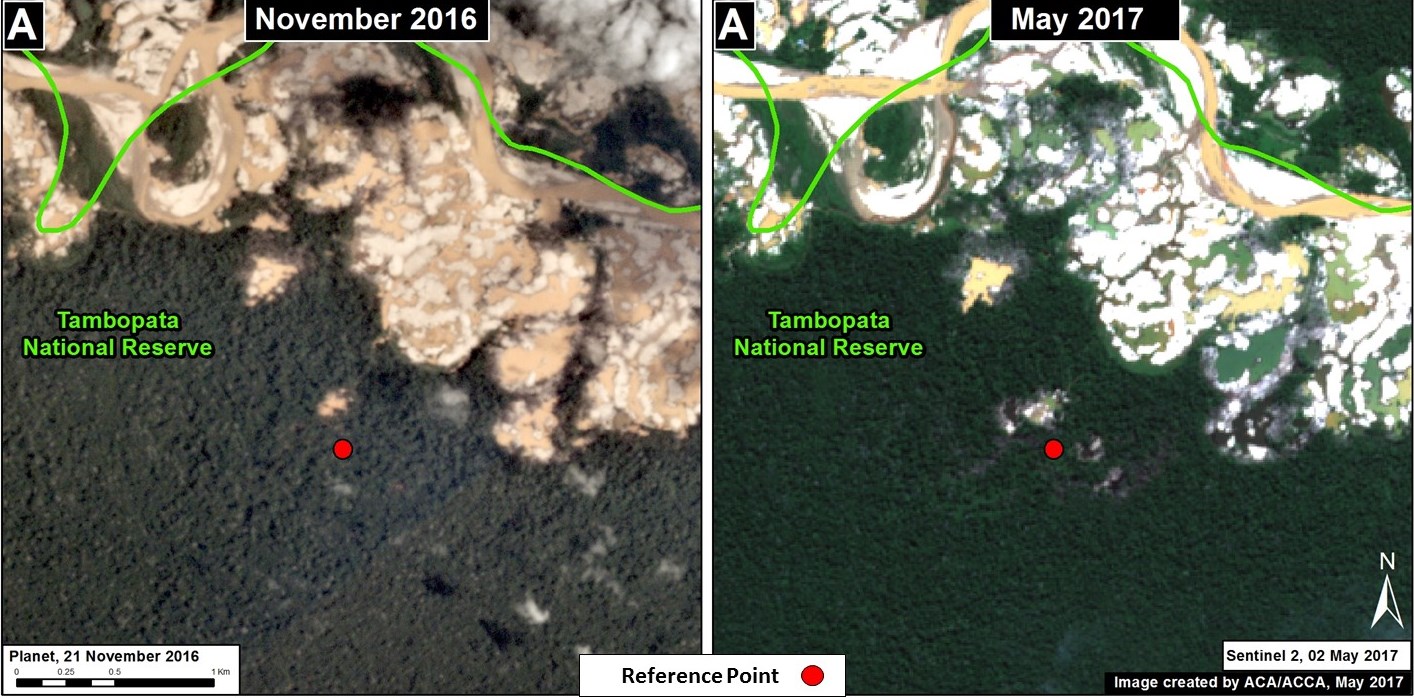

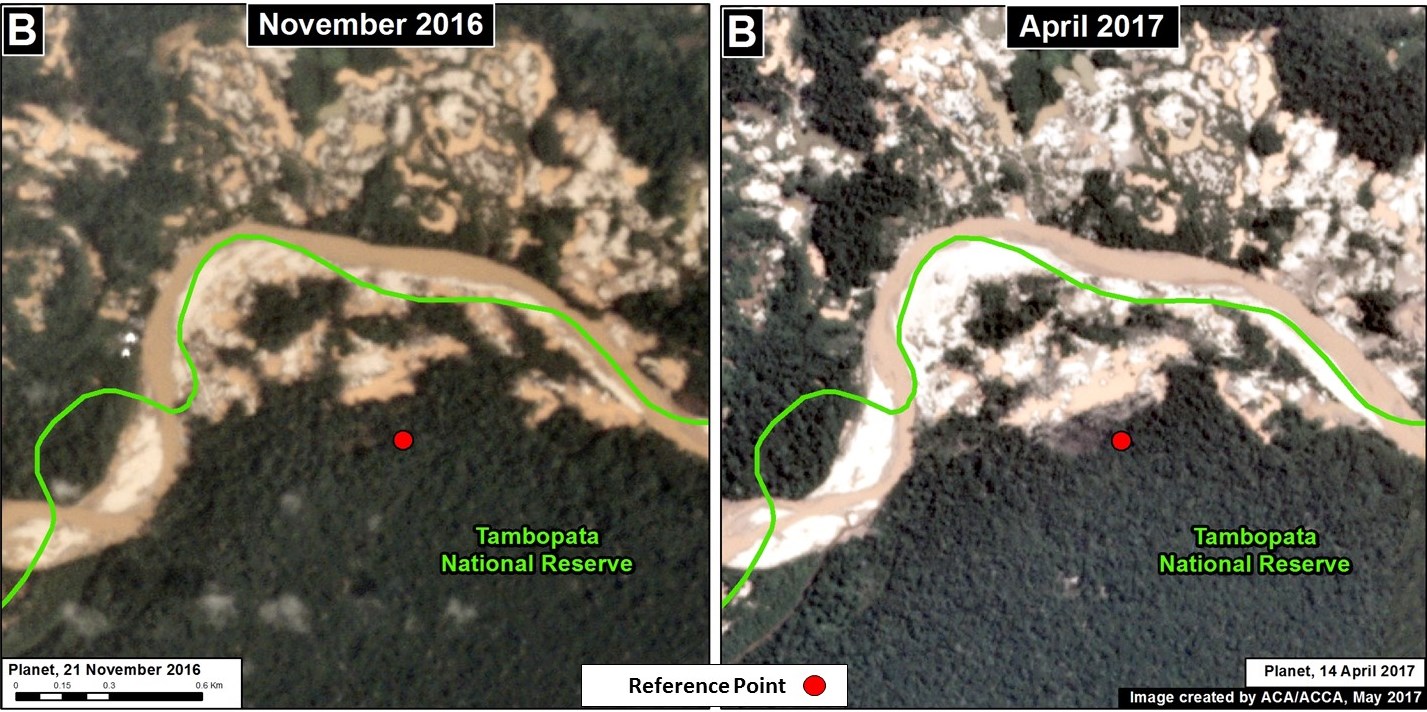

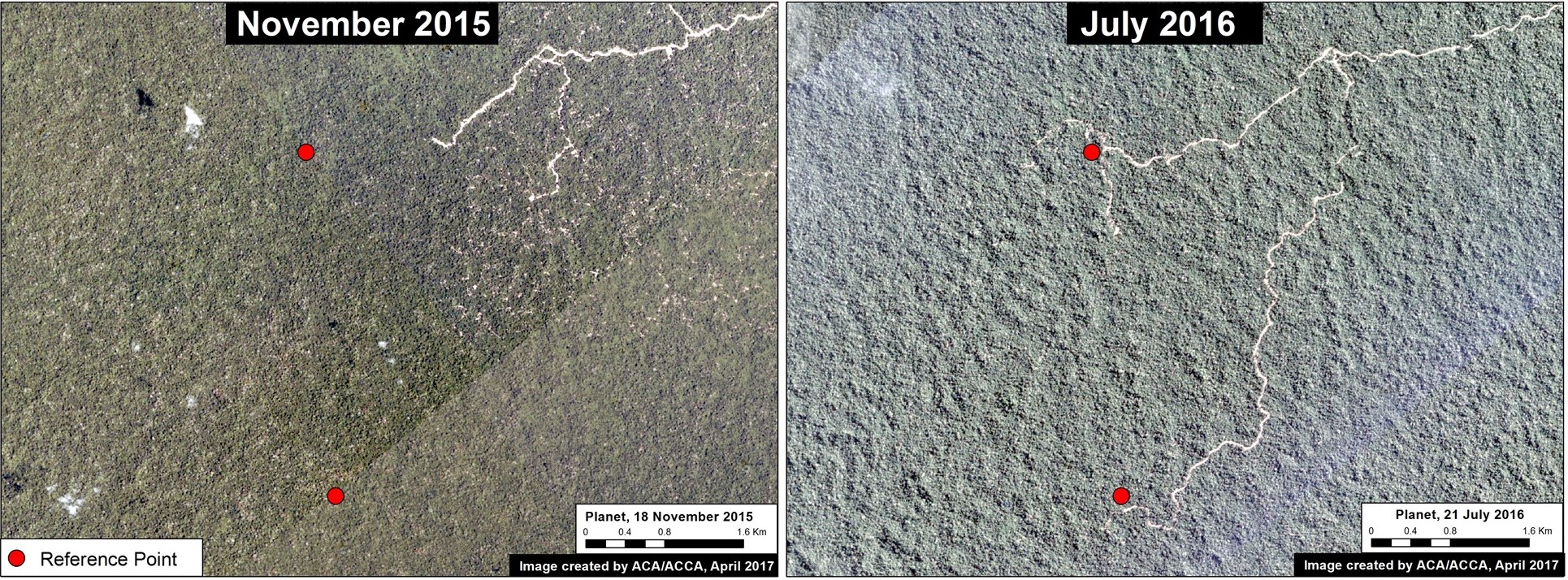

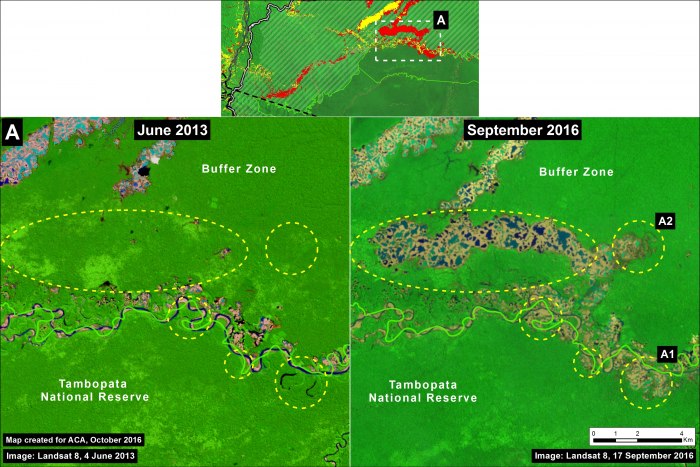

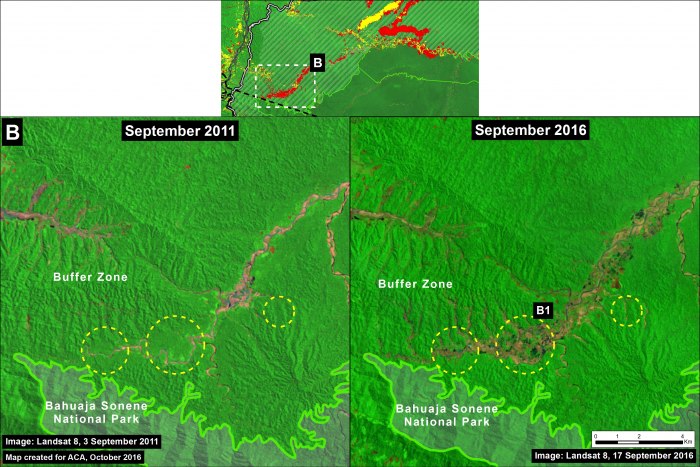

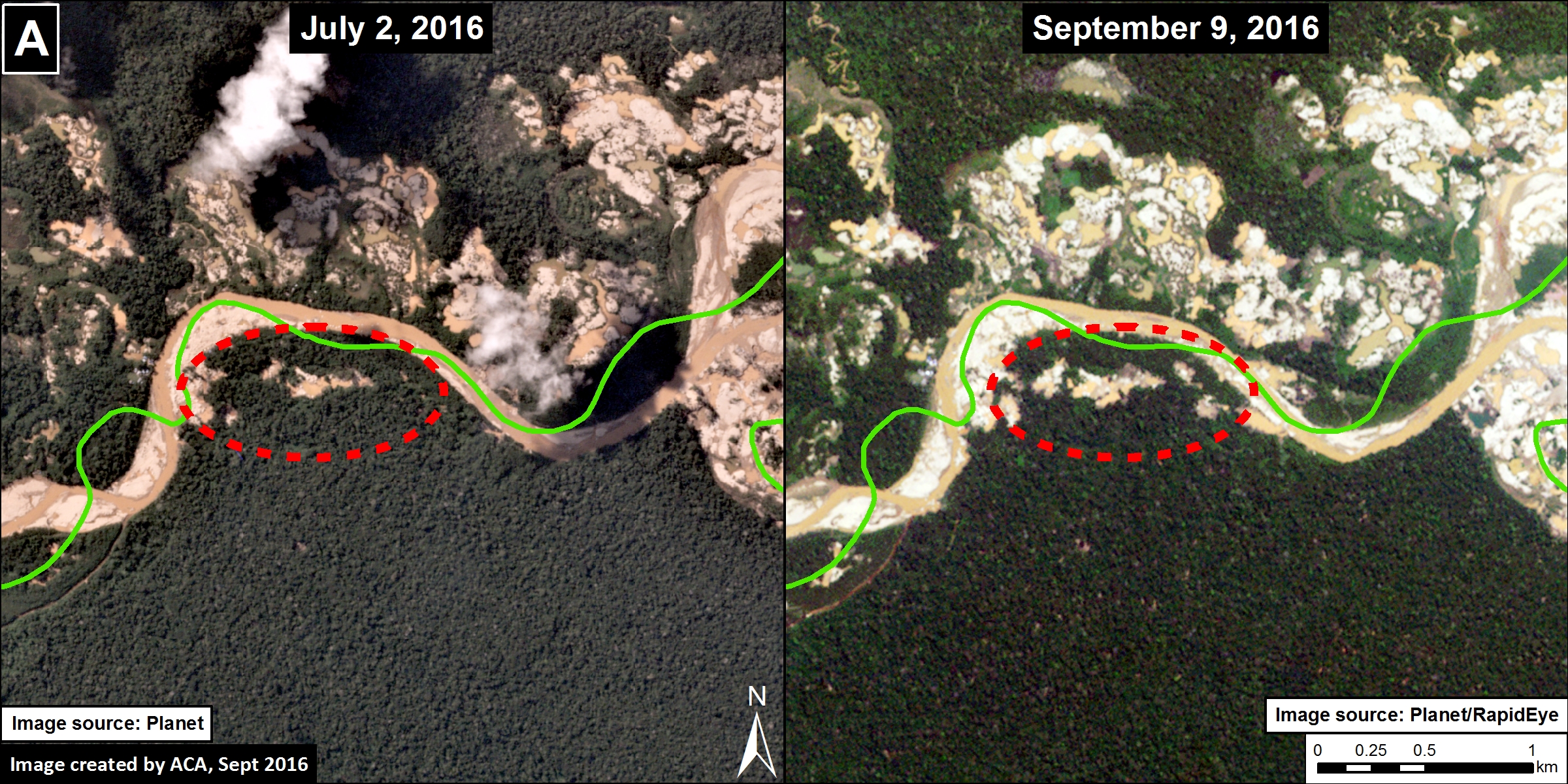

Most notably, we have closely tracked the illegal gold mining invasion of Tambopata National Reserve, an important protected area in the Madre de Dios region with renowned biodiversity and ecotourism. The initial invasion occurred in November 2015 (MAAP #21), and has steadily expanded to over 1,110 acres (MAAP #24, MAAP #30, MAAP #46). As part of this invasion, miners have modified the natural course of the Malinowski River, which forms the natural northern border of the reserve (MAAP #33). In addition, illegal gold mining deforestation continues to expand within the reserve’s buffer zone, particularly in an area known as La Pampa (MAAP #12, MAAP #31).

Further upstream, illegal gold mining is also expanding on the upper Malinowski River, within the buffer zone of Bahuaja Sonene National Park (MAAP #19, MAAP #43).

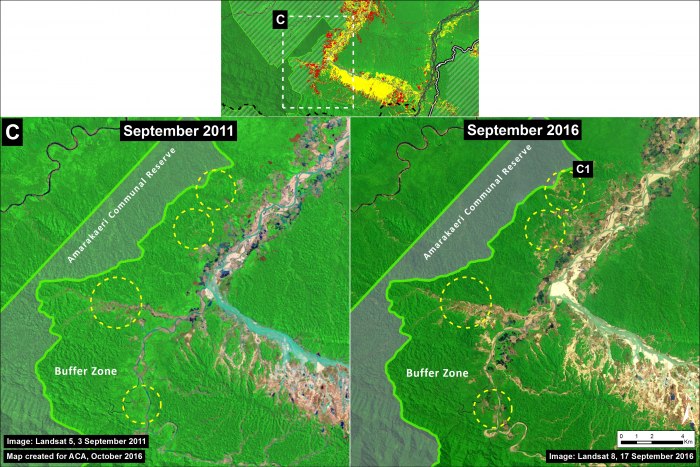

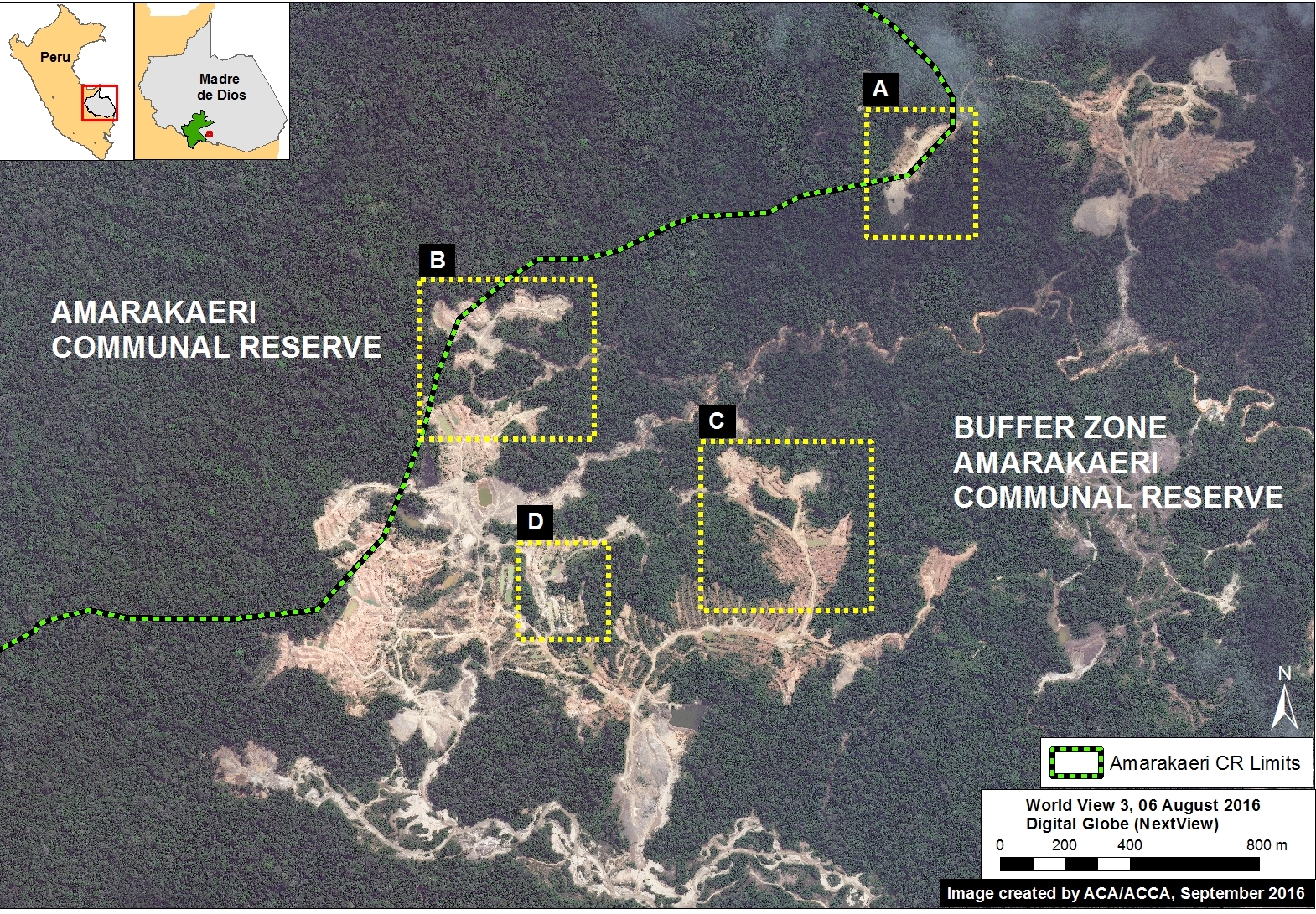

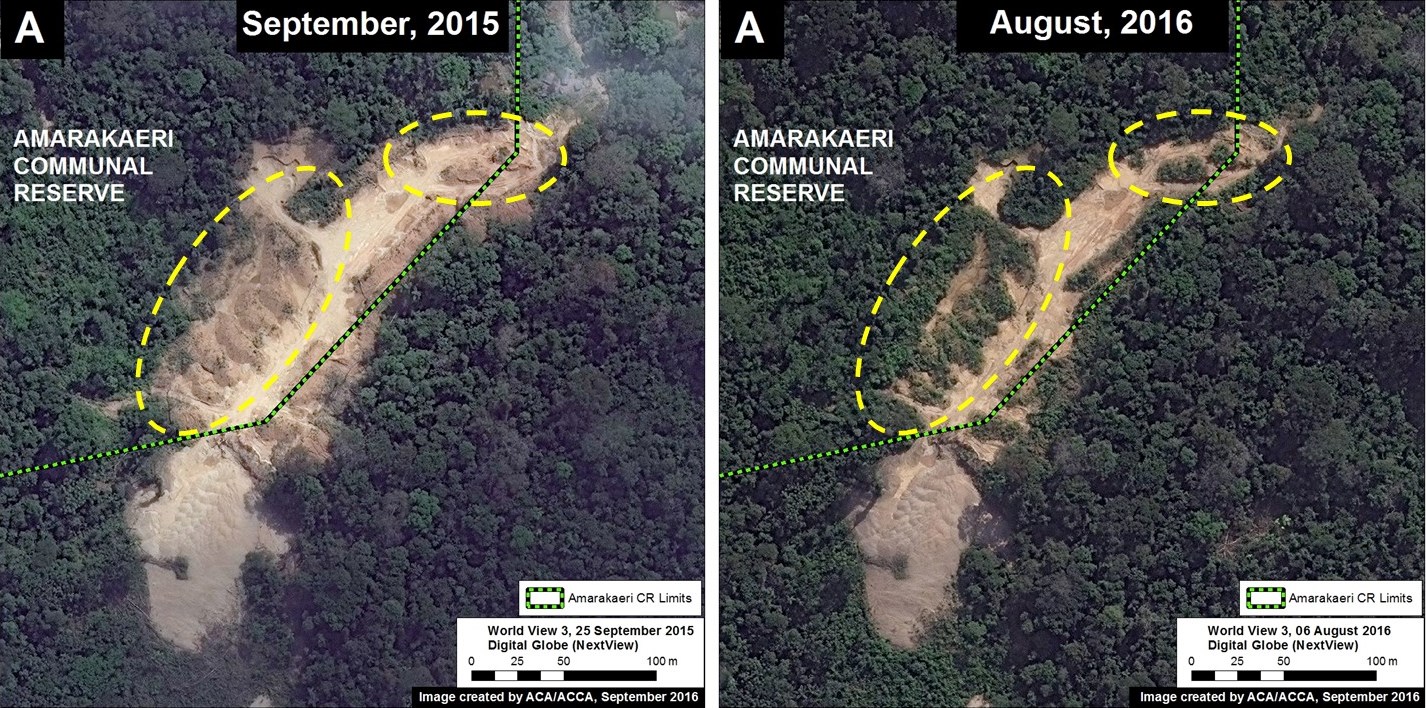

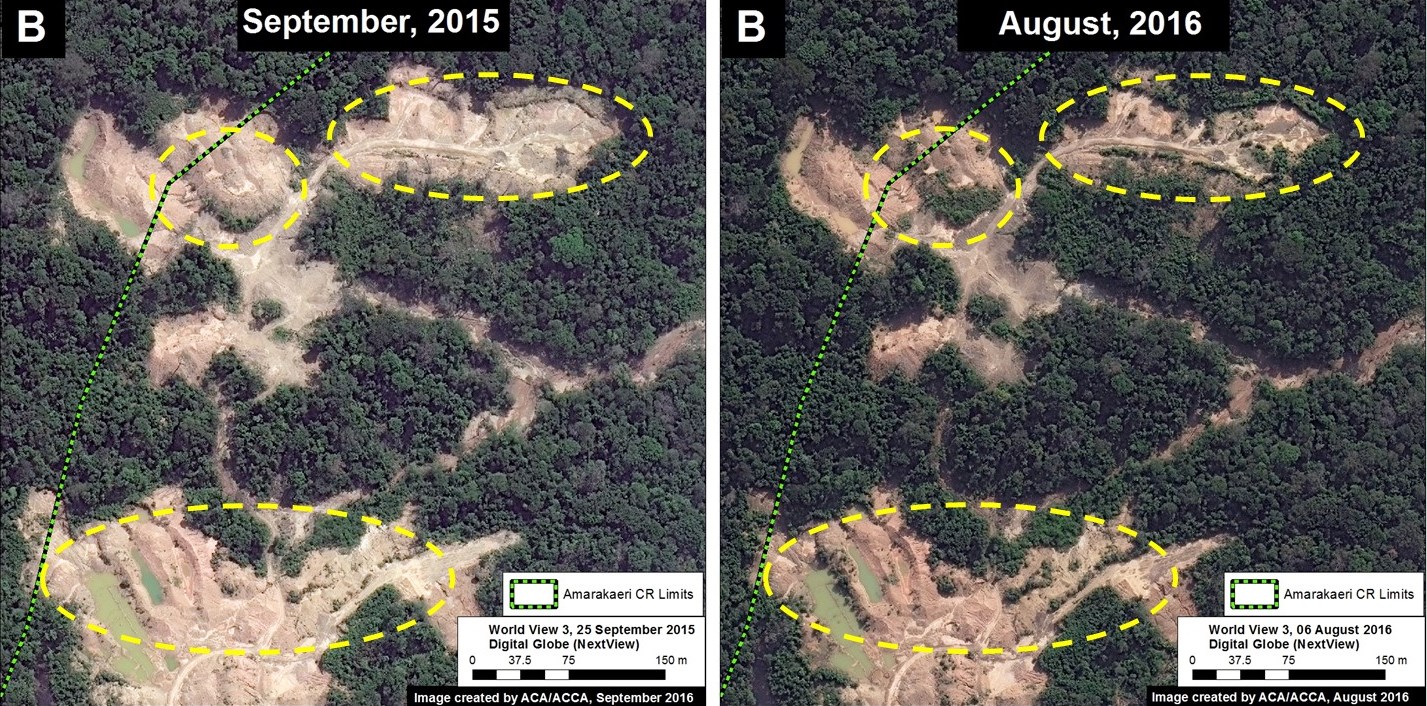

In contrast to the escalating situation in Tambopata, we also documented that gold mining deforestation has been contained in the nearby Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, an important protected area that is co-managed by indigenous communities and Peru’s national protected areas agency. Following an initial invasion of 27 acres in 2014 and early 2015, satellite imagery shows that management efforts have prevented any subsequent expansion within the protected area (MAAP #6, MAAP #44).

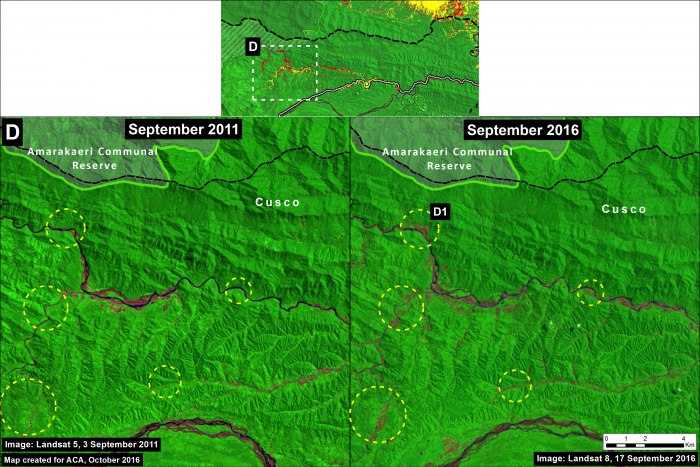

In addition to the above cases in Madre de Dios, gold mining deforestation is also increasingly an issue in the adjacent regions of Cusco and Puno (MAAP #14).

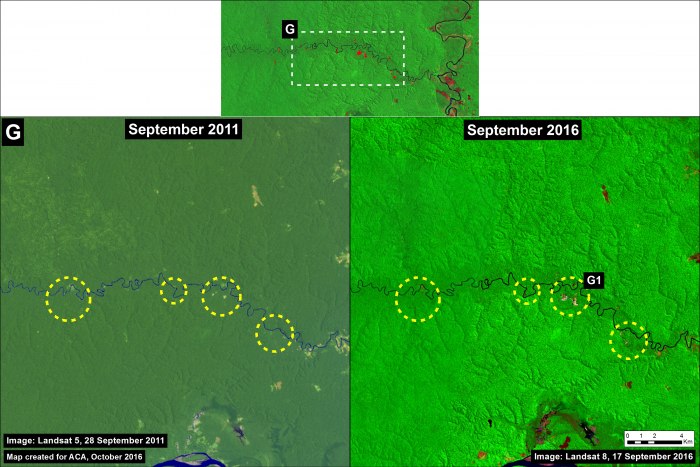

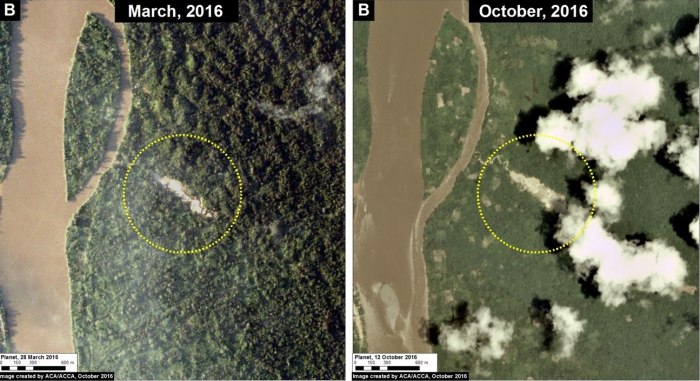

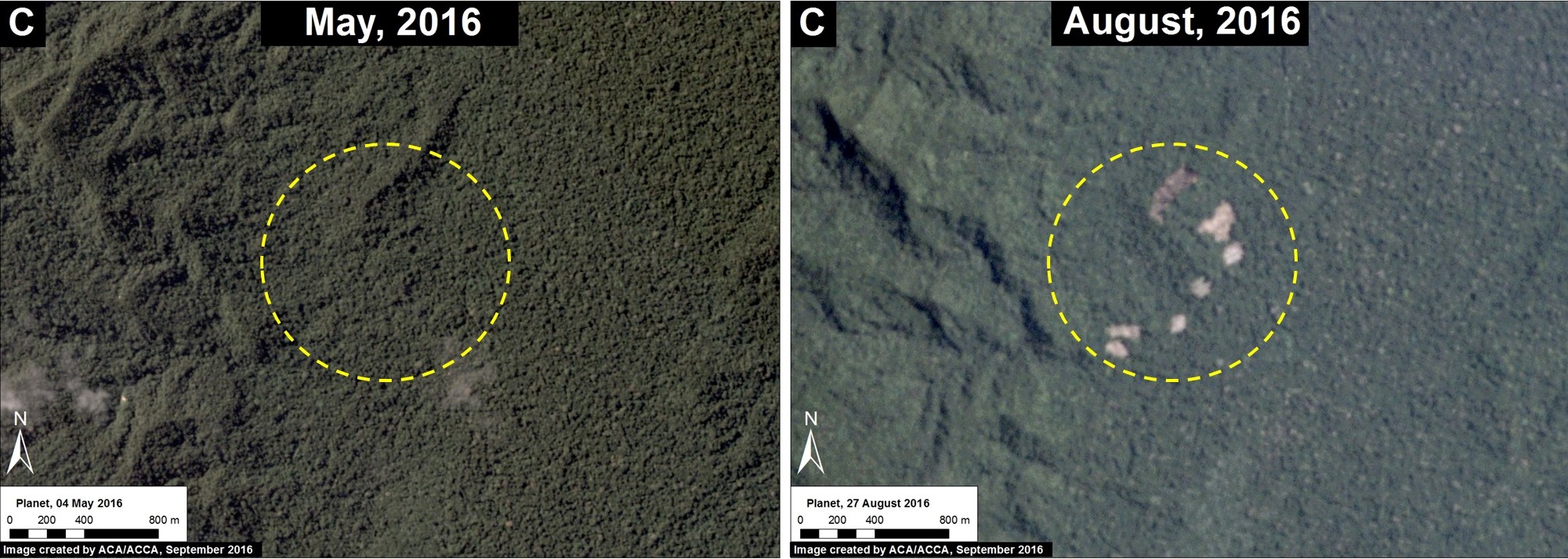

There are several small, but potentially emerging, gold mining frontiers in the central and northern Peruvian Amazon (MAAP #49). The Peruvian government has been working to contain the illegal gold mining in the El Sira Communal Reserve (MAAP #45). Further north in Amazonas region, there is gold mining deforestation along the Rio Santiago (MAAP #36, MAAP #49), and in the remote Condor mountain range along the border with Ecuador (MAAP #49).

Roads

Roads are a well-documented driver of deforestation in the Amazon, particularly due to their ability to facilitate human access to previously remote areas.10 Roads often serve as an indirect driver, as most of the deforestation directly associated with agriculture, cattle pasture, and gold mining is likely greatly facilitated by proximity to roads. We documented the start of a controversial road construction project that would cut through the buffer zones of two important protected areas, Amarakaeri Communal Reserve and Manu National Park (MAAP #29).

Logging Roads

In relation to general roads described above, we distinguish access roads that are constructed to gain entry to a particular project. The most notable type of access roads in Peru are logging roads, which are likely a leading cause of forest degradation as they facilitate selective logging of valuable timber species in remote areas.

One of the major recent advances in forest monitoring is the ability to quickly identify the construction of new logging roads. The unique linear pattern of these roads appears quite clearly in Landsat-based tree cover loss alerts such as GLAD and CLASlite. This advance is important because it is difficult to detect illegal logging in satellite imagery because loggers in the Amazon often selectively cut high value species and do not produce large clearings. But now, although it remains difficult to detect the actual selective logging, we can detect the roads that indicate that selective logging is taking place in that area.

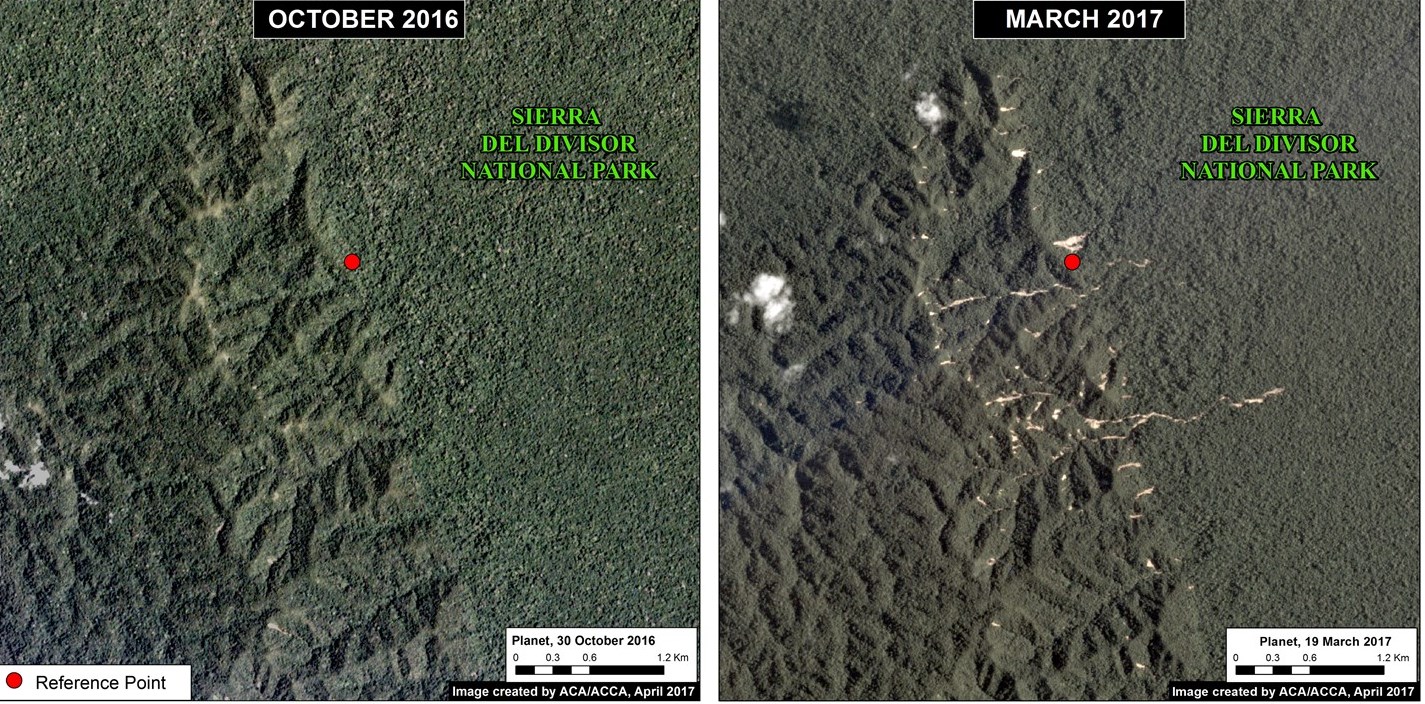

In a series of articles, we highlighted the recent expansion of logging roads, including the construction of 1,134 km between 2013 and 2015 in the central Peruvian Amazon (MAAP #3, MAAP #18). Approximately one-third of these roads were within the buffer zones of Cordillera Azul and Sierra del Divisor National Parks (MAAP #15).

We documented the construction of an additional 83 km of logging roads during 2016, (MAAP #40, MAAP #43) including deeper into the buffer zone of Cordillera Azul National Park.

Another major finding is the rapid construction of the logging roads. In several cases, we documented the construction rate of nearly five kilometers per week (MAAP #18, MAAP #40, MAAP #43).

Determining the legality of these logging roads is complex, partly because of the numerous national and local government agencies involved in the authorization process. Many of these roads are near logging concessions and native communities, whom may have obtained the rights for logging from the relevant forestry authority (in many cases, the regional government).

Coca

According to a recent United Nations report, the Peruvian land area under coca cultivation in 2015 (99,580 acres) was the lowest on record (since 2001) and part of a declining trend since 2011 (154,440 acres).11 There are 13 major coca growing zones in Peru, but it appears that only a few of them are actively causing new deforestation. Most important are two coca zonas in the region of Puno that are causing deforestation within and around Bahuaja Sonene National Park (MAAP #10, MAAP #14). Several coca zones in the regions of Cusco and Loreto may also be causing some new deforestation.

Hydroelectric Dams

Although there is a large portfolio of potential new hydroelectric dam projects in the Peruvian Amazon,12 many of not advanced to implementation phase. Thus, forest loss due to hydroelectric dams is not currently a major issue, but this could quickly change in the future if these projects are revived. For example, in adjacent western Brazil, we documented the forest loss of 89,205 acres associated with the flooding caused by two dams on the upper Madeira River (MAAP #34).

Hydrocarbon (Oil & Gas)

During the course of our monitoring, we have not yet detected major deforestation events linked to hydrocarbon-related activities. As with dams, this could change in the future if oil and gas prices rise and numerous projects in remote corners of the Amazon move forward.

Methodology

MAAP methodology has 4 major components:

- Forest Loss Detection. MAAP reports rely heavily on early-warning tree cover loss alerts to help us identify where new deforestation is happening. Currently, our primary tool is GLAD alerts, which are developed by the University of Maryland and Google,13 and presented by WRI’s Global Forest Watch and Peru’s GeoBosques. These alerts, launched in Peru in early 2016, are based on 30-meter resolution Landsat satellite images and updated weekly. We also occasionally incorporate CLASlite, forest loss detection software based on Landsat (and now Sentinel-2) developed by the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the moderate resolution (250 meters) Terra-i alerts. We are also experimenting with Sentinel-1 radar data (freely available from the European Space Agency), which has the advantage of piercing through cloud cover in order to continue monitoring despite persistent cloudy conditions

- Prioritize Big Data. The early warning systems noted above yield thousands of alerts, thus a procedure to prioritize the raw data is needed. We employ numerous prioritization methods, such as creation of hotspot maps (see below), focus on key areas (such as protected areas, indigenous territories, and forestry concessions), and identification of striking patterns (such as linear features or large-scale clearings).

- Identify Deforestation Drivers. Once priority areas are identified, the next challenge is to understand the cause of the forest loss. Indeed, one of the major advances of MAAP over the past year has been using high-resolution satellite imagery to identify key deforestation drivers. Our ability to identify these deforestation drivers has been greatly enhanced thanks to access to high-resolution satellite imagery provided by Planet 14

(via their Ambassador Program) and Digital Globe (via the NextView Program, courtesy of an agreement with USAID). We also occasionally purchase imagery from Airbus(viaApollo Mapping).

- Publish User-Friendly Reports. The final step is to publish technical, but accessible, articles highlighting novel and important findings on the MAAP web portal. These articles feature concise text and easy-to-understand graphics aimed at a wide audience, including policy makers, civil society, researchers, students, journalists, and the public at large. During preparation of these articles, we consult with Peruvian civil society and relevant government agencies in order to improve the quality of the information.

Endnotes

1 MINAM-Peru (2016) Estrategia Nacional sobre Bosques y Cambio Climático.

2 Methodology: Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGis. The 2016 data is based on GLAD alerts, while the 2012-15 data is based on official annual forest loss data

3 Ravikumar et al (2016) Is small-scale agriculture really the main driver of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon? Moving beyond the prevailing narrative. Conserv. Lett. doi:10.1111/conl.12264

4 Gutiérrez-Vélez VH et al (2011). High-yield oil palm expansion spares land at the expense of forests in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett., 6, 044029.

5 Environmental Investigation Agency EIA (2015) Deforestation by Definition.

6 NG J (2015) United Cacao replicates Southeast Asia’splantation model in Peru, says CEO Melka. The Edge Singapore, July 13, 2015.

7 Palmas del Shanusi & Palmas del Oriente; http://www.palmas.com.pe/palmas/el-grupo/empresas

8 Hill D (2015) Palm oil firms in Peru plan to clear 23,000 hectares of primary forest. The Guardian, March 7, 2015.

9 Asner GP, Llactayo W, Tupayachi R, Ráez Luna E (2013) Elevated rates of gold mining in the Amazon revealed through high-resolution monitoring. PNAS 46: 18454. They reported 46,417 hectares confirmed and 3,268 hectares suspected (49,865 ha total).

10 Laurance et al (2014) A global strategy for road building. Nature 513:229; Barber et al (2014) Roads, deforestation, and the mitigating effect of protected areas in the Amazon. Biol Cons 177:203.

11 UNODC/DEVIDA (2016) Perú – Monitoreo de Cultivos de Coca 2015.

12 Finer M, Jenkins CN (2012) Proliferation of Hydroelectric Dams in the Andean Amazon and Implications for Andes-Amazon Connectivity. PLoS ONE 7(4): e35126.

13 Hansen MC et al (2016) Humid tropical forest disturbance alerts using Landsat data. Environ Res Lett 11: 034008.

14 Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S (2017) Patterns and Drivers of Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: Synthesis #2.