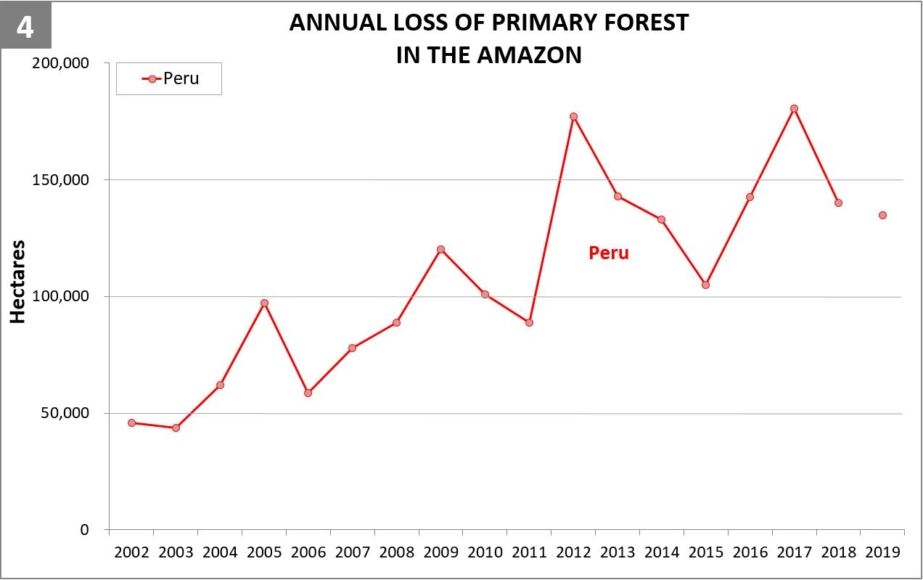

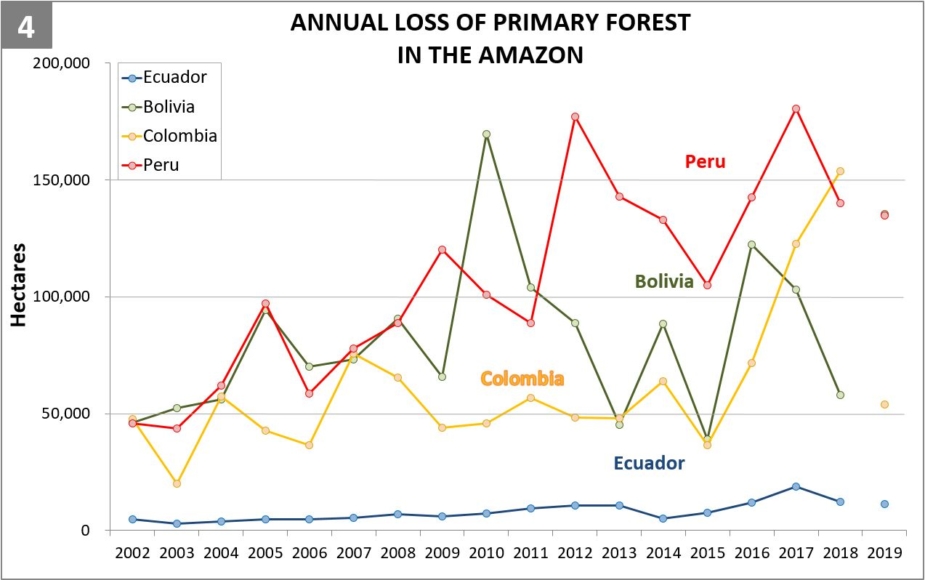

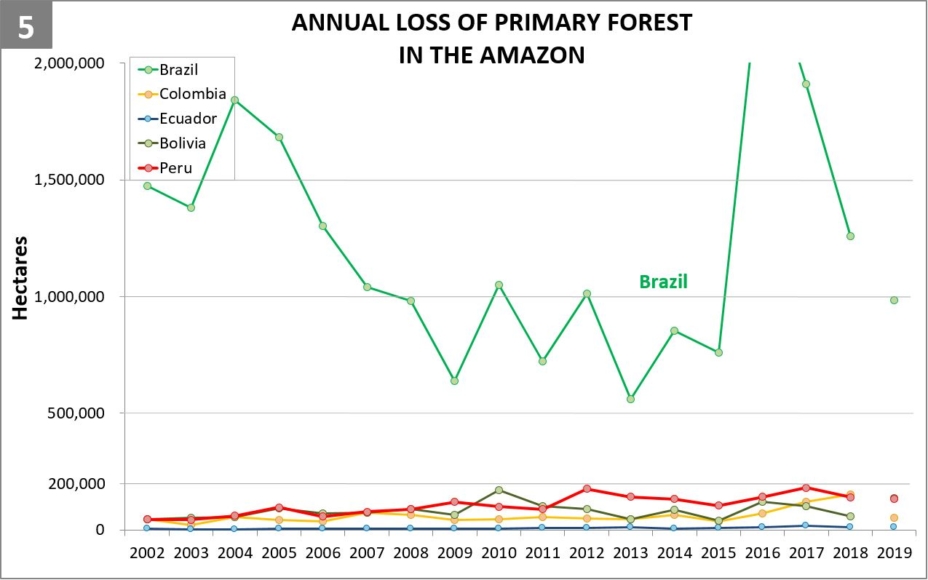

These graphs correspond to MAAP Synthesis: 2019 Amazon Deforestation Trends and Hotspots.

Countries>Peru

MAAP #115: Illegal Gold Mining in the Amazon, part 1: Peru

In a new series, we highlight the main illegal gold mining frontiers in the Amazon.

Here, in part 1, we focus on Peru. In the upcoming part 2, we will look at Brazil.

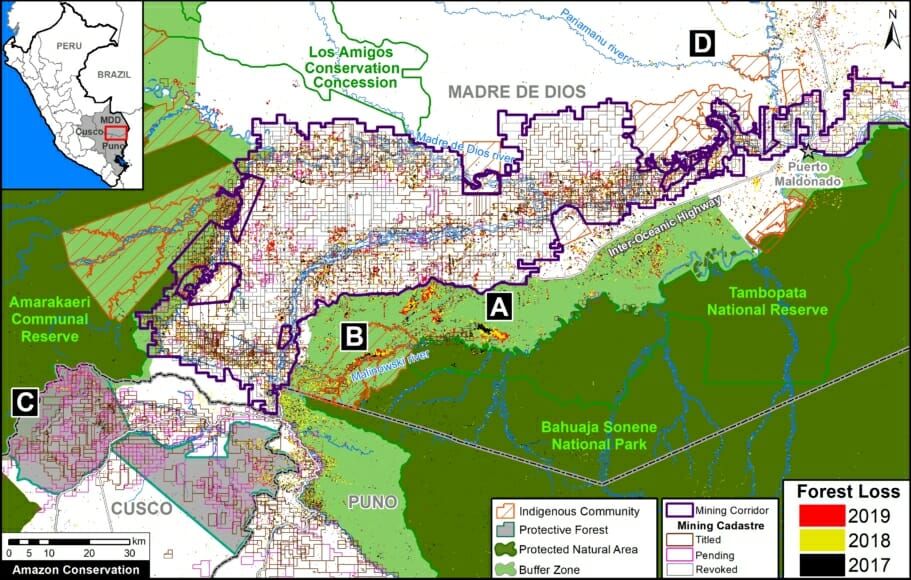

The Base Map indicates our focus areas in Peru*:

- Southern Peru (A. La Pampa, B. Alto Malinowski, C. Camanti, D. Pariamanu);

- Central Peru (E. El Sira).

Notably, we found an important reduction in gold mining deforestation in La Pampa (Peru’s worst gold mining area) following the government’s launch of Operation Mercury in February 2019.

Illegal gold mining continues, however, in three other major areas of the southern Peruvian Amazon (Alto Malinowski, Camanti, and Pariamanu), where we estimate the mining deforestation of 5,300 acres (2,150 hectares) since 2017.

Of that total, 22% (1,162 acres) occurred in 2019, indicating that displaced miners from Operation Mercury have NOT caused a surge in these three areas.

Below, we show a series of satellite videos of the recent gold mining deforestation (2017-19) in each area.

*Recent press reports indicate the increase in illegal gold mining activity in northern Peru (Loreto region), along the Nanay and Napo Rivers, but we have not yet detected associated deforestation.

A. La Pampa (Southern Peru)

In MAAP #104, we reported a major reduction (92%) of gold mining deforestation in La Pampa during the first four months of Operation Mercury, a governmental mega-operation to confront the illegal mining crisis in this area.

The following video shows how gold mining deforestation has declined considerably since February 2019, the beginning of the operation. Note the rapid deforestation during the years 2016-18, followed by a sudden stop in 2019.

B. Alto Malinowski (Southern Peru)

The following video shows gold mining deforestation in a section of the upper Malinowski River (Madre de Dios region). We estimate the mining deforestation of 4,120 acres (1,668 hectares) throughout the Alto Malinowski area during the 2017 – 2019 period.

Of that total, 20% (865 acres) occurred in 2019, indicating that displaced miners from Operation Mercury have not caused a surge in this area adjacent to La Pampa.

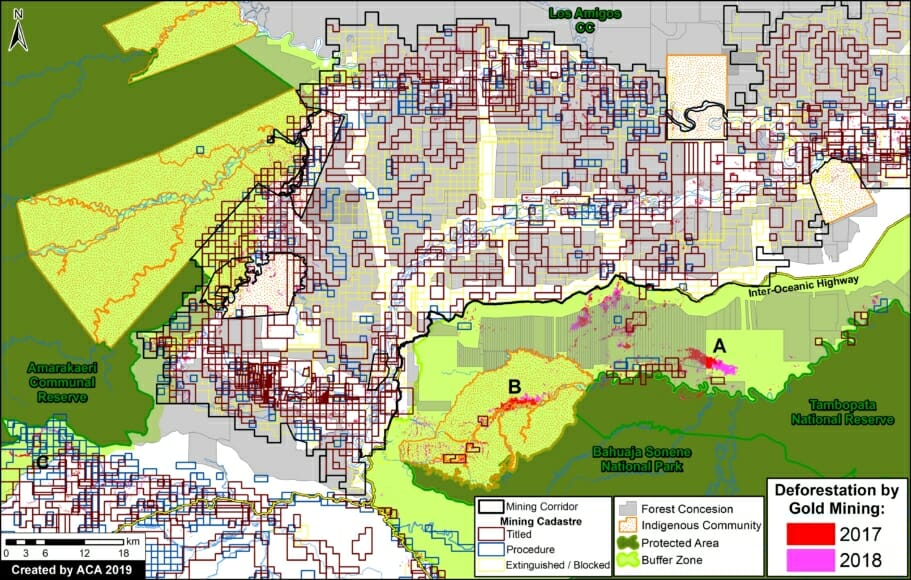

According to our analysis of governmental information (see Annex 2), the recent mining activity is likely illegal because: a) much of it occurs outside of titled mining concessions, b) and all of it occurs outside of the mining corridor established for legal mining activity (see Annex 1).

Note that the mining deforestation is within the Kotsimba Indigenous Community territory. However, it has not penetrated Bahuaja Sonene National Park, in part due to the actions of the Peruvian Protected Areas Service (SERNANP).

C. Camanti (Southern Peru)

The following video shows the gold mining deforestation of 944 acres (382 hectares) in the Camanti district (Cusco region), during the 2017 – 2019 period.

Of that total, 21% (198 acres) occurred in 2019, indicating that there has been no increase in mining activity in this area since the beginning of Operation Mercury in February (in contrast to press reports that have suggested that many displaced miners have moved to this area).

According to governmental information (see Annex 2), this mining activity is likely illegal because: a) much of it occurs outside of titled mining concessions, b) all occurs outside of the mining corridor, and c) all occurs inside both a protected forest (Bosque Protector) and buffer zone of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

SERNANP (Peruvian Protected Areas Service) informed us that in December 2019, as part of Operation Mercury, the Public Ministry (Ministerio Público) led an interdiction with the support of law enforcement. Machinery, mining camps, and mercury were destroyed or removed during the raid. In 2020, as part of an extension of Operation Mercury, the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office (FEMA) of the Public Ministry announced that the buffer zone of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve will be constantly monitored.

D. Pariamanu (Southern Peru)

The following video shows gold mining activity along a section of the Pariamanu River (Madre de Dios region). We estimate the gold mining deforestation of 245 acres (99 hectares) in the Pariamanu area, during the 2017 – 2019 period.

Of that total, 40% (99 acres) occurred in 2019, indicating that there has been a slight increase in mining activity since the beginning of Operation Mercury in February. This finding suggests that displaced miners may be moving to this area.

According to governmental information (see Annex 2), this mining activity is likely illegal because it is not within active mining concessions and outside the mining corridor. Morevoer, the mining deforestation is within Brazil nut forestry concessions.

E. El Sira (Central Peru)

The following video shows the gold mining deforestation of 52 acres (21 hectares) in the buffer zone of El Sira Communal Reserve (Huánuco region), during the 2017 – 2019 period.

Although the mining activity occurs in an active mining concession, a recent report indicates that it is illegal because it does not have the deforestation authorization.

Annex 1: Mining Corridor

The mining corridor is the area that the Peruvian Government has defined as potentially legal for mining activity in the Madre de Dios region via a formalization process. As of 2019, over 100 miners have been formalized in Madre de Dios.

In general, mining activity in the corridor is considered legal, either formaly (the formalization process is completed with environmental and operational permits approved) or informaly (in the process of formalization). Thus, mining activity within the corridor is not considered illegal since it is not a prohibited area.

The following two videos show examples of gold mining deforestation in the mining corridor during 2019.

Annex 2: Land Use Map

For greater context, we present a map of qualifying titles directly related to the mining sector, in southern Peru. Layers include the mining corridor (see above), mining concession status (titled, pending, revoked), indigenous territories, and protected areas.

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Ortiz (AAF), A. Flórez (SERNANP), P. Rengifo (ACCA), A. Condor (ACCA), A. Folhadella (Amazon Conservation), and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: NASA/USAID (SERVIR), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, Erol Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) Illegal Gold Mining Frontiers, part 1: Peru. MAAP: 115.

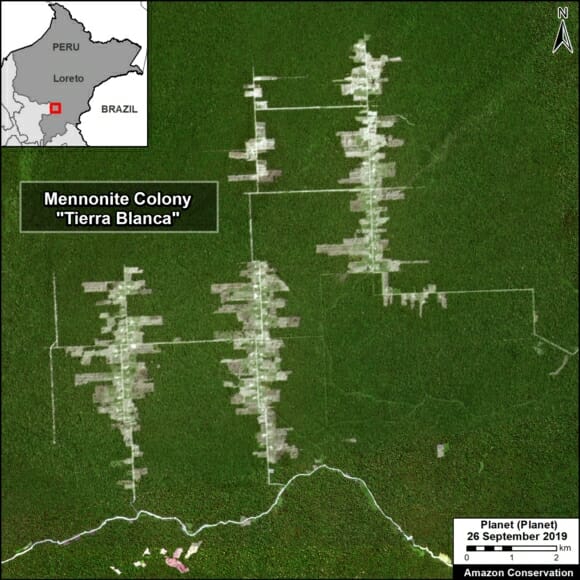

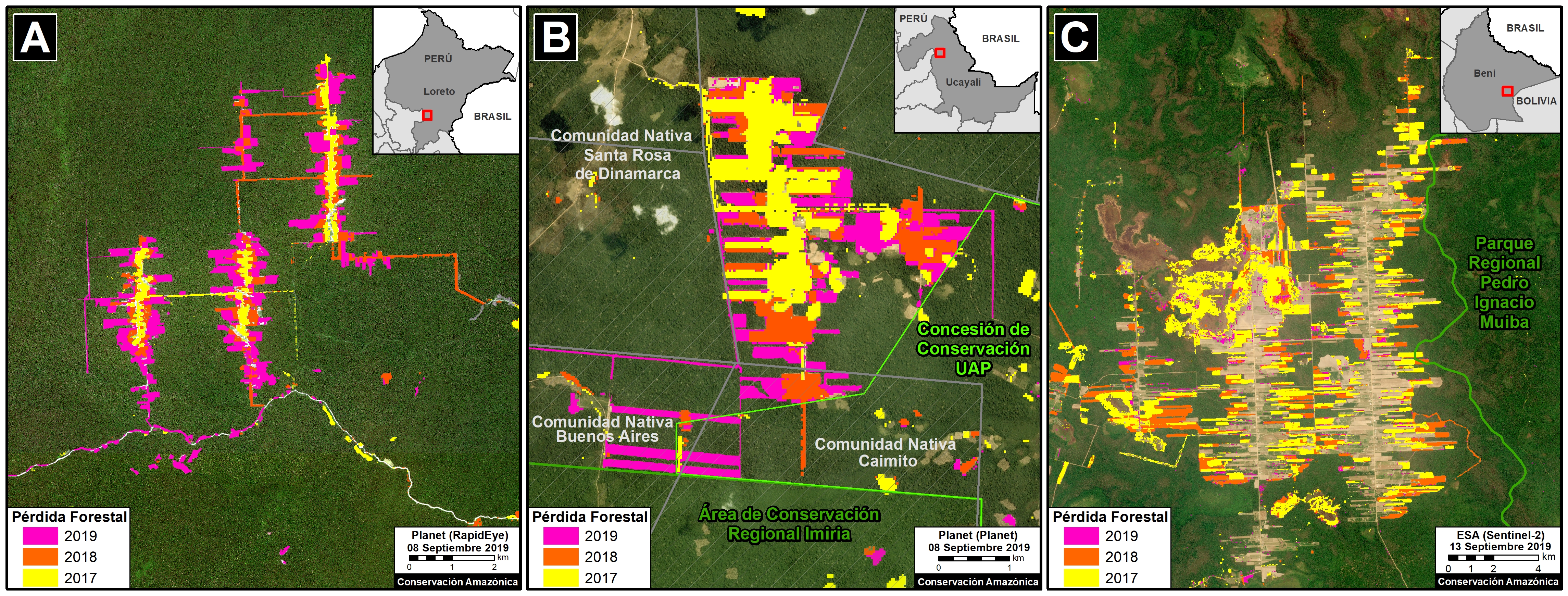

MAAP #112: Mennonite Colonies – New Deforestation Driver in the Amazon

The Mennonites, a religious (Christian) group often dedicated to organized agriculture, are increasingly inhabiting the western Amazon (Peru and Bolivia).

Here, we reveal the recent deforestation of 18,500 acres (7,500 hectares) in three Mennonite colonies (see the Base Map below).

The two colonies in Peru (Tierra Blanca and Masisea) are new, causing the deforestation of 6,200 acres since 2017 (including 3,500 acres in 2019) in the Loreto and Ucayali regions.

The colony in Bolivia (Río Negro) is older, but deforestation recently began to increase again, causing the deforestation of 12,350 acres since 2017 in the department of Beni.

Next, we present a series of satellite image videos showing the deforestation in the three Mennonite colonies.

Tierra Blanca (Perú)

The Mennonite colony referred to here as “Tierra Blanca” is located in southern Loreto region, near the town of Tierra Blanca.

Video A shows the deforestation of 4,200 acres in the Tierra Blanca colony since 2017 (Planet link). We note that 2019 experienced the most deforestation (2,470 acres).

Masisea (Perú)

The Mennonite colony referred to here as “Masisea” is located in northern Ucayali region, near the town of Masisea.

Video B shows the deforestation of 2,000 acres in the Masisea colony since 2017 (Planet link). We note that 2019 experienced the most deforestation (865 acres).

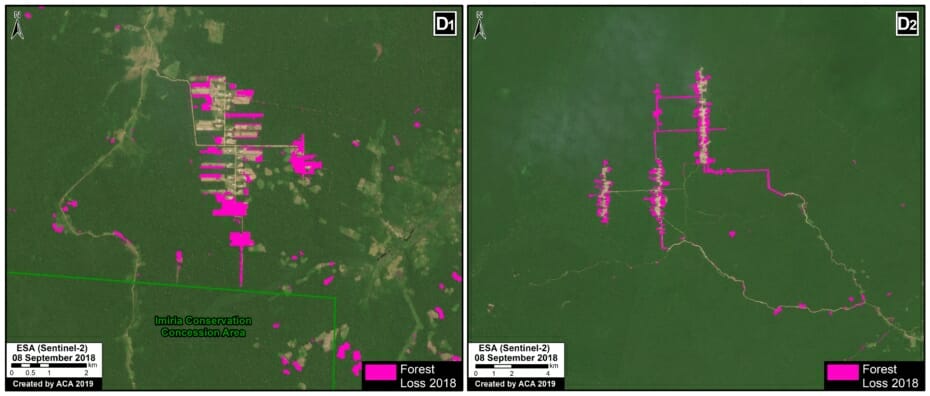

In the detailed map in the Annex, note that the deforestation has reached the limit of a protected area, Imiría Regional Conservation Area. In addition, deforestation has occurred within two native communities (Buenos Aires and Caimito) and a Conservation Concession managed by a Peruvian university.

Río Negro (Bolivia)

The Mennonite colony Río Negro is located in southeastern Beni department. There are several Mennonite colonies in southern Bolivia, but this is one of the first deeper in the Amazon (Kopp, 2015).

Video C shows the deforestation of 12,350 acres in the Río Negro colony since 2017 (Planet link). Much of the deforestation occurred in 2017-18.

Annex 1: Base Map

Annex 2: Detailed Maps

References

Kopp Ad (2015) Las colonias menonitas en Bolivia. Tierra. http://www.ftierra.org/index.php/publicacion/libro/147-las-colonias-menonitas-en-bolivia

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Balbuena, A. Condor, and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), MacArthur Foundation, International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2019) Mennonite Colonies: New Deforestation Driver in the Amazon. MAAP: 112.

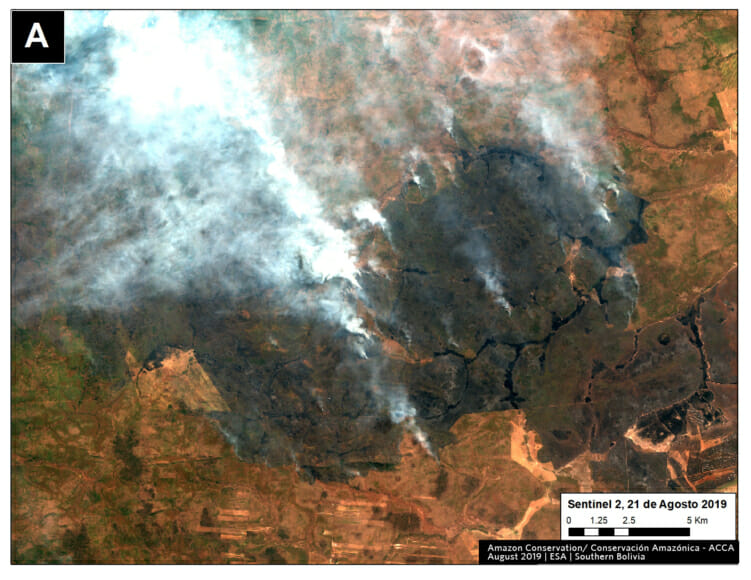

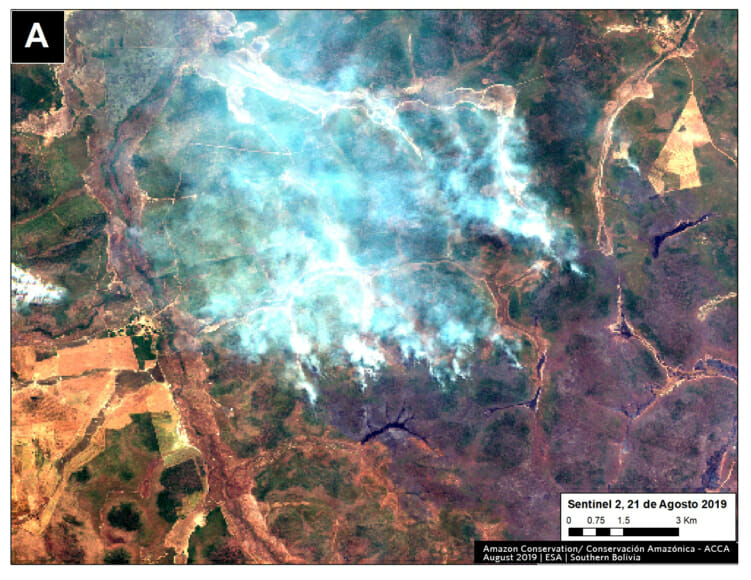

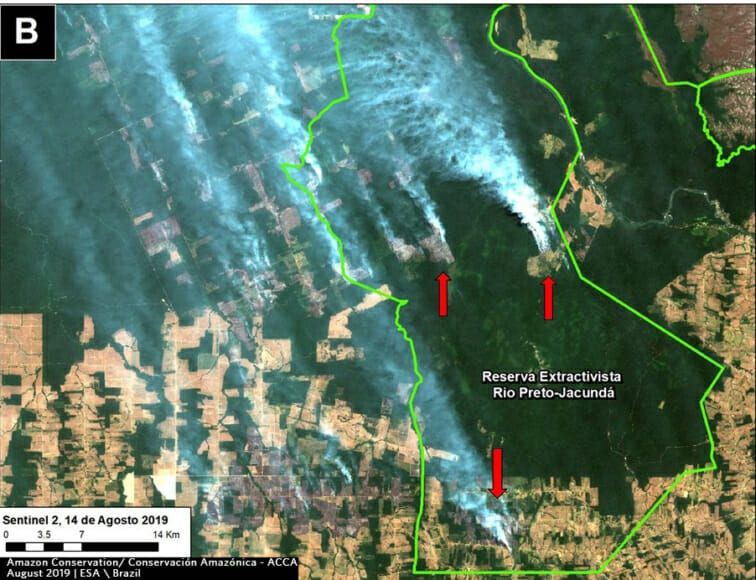

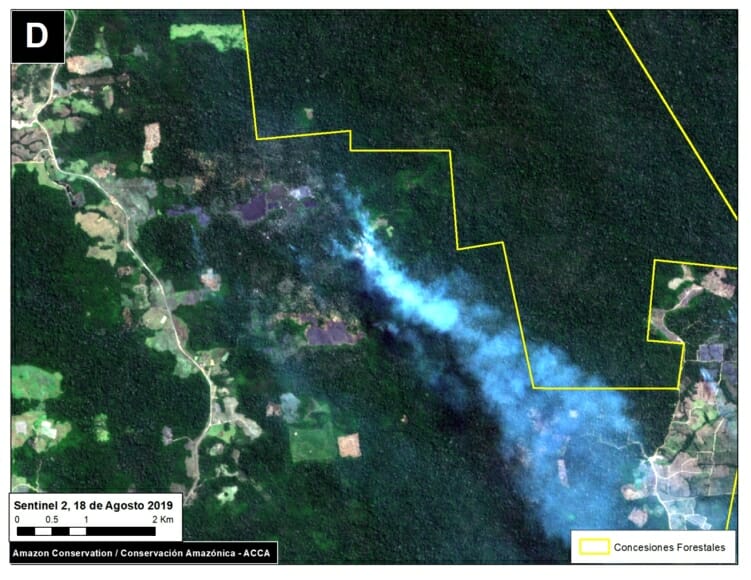

MAAP #107: Seeing the Amazon Fires with Satellites

Fires now burning in the Amazon, particularly Brazil and Bolivia, have become headline news and a viral topic on social media.

Yet little information exists on the impact on the Amazon rainforest itself, as many of the detected fires originate in or near agricultural lands.

Here, we advance the discussion on the impact of the fires by presenting the first Base Map of current “fire hotspots” across three countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru). We also present a striking series of satellite images that show what the fires look like in each hotspot and how they are impacting Amazonian forests. Our focus is on the most recent fires in August 2019.

Our key findings include:

- Fires are burning Amazonian forest in Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru.

. - The fires in Bolivia are concentrated in the dry Chiquitano forests in the southern Amazon.

. - The fires in Brazil are much more scattered and widespread, often associated with agricultural lands. Thus, we warn against using fire detection data alone as a measure of impact as many are clearing fields. However, many of the fires are at the agriculture-forest boundary and maybe expanding plantations or escaping into forest.

. - Although not as severe, we also detected fires burning forest in southern Peru, in an area that has become a deforestation hotspot along the Interoceanic Highway.

Given the nature of the fires in Bolivia and Brazil, estimates of total burned forest area are still difficult to determine. We will continue monitoring and reporting on the situation over the coming days.

Base Map

The Base Map shows “fire hotspots” for the Amazonian regions of Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru in August 2019. The data comes from a NASA satellite that detects fires at 375 meter resolution. The letters (A-G) correlate to the satellite image zooms below.

Zoom A: Southern Bolivian Amazon

Fires are concentrated in the dry Chiquitano of southern Bolivia. It is part of the largest tropical dry forest in the world. The fires coincide with areas that have been part of cattle ranching expansion in recent decades (References 1 and 2), suggesting that poor burning practices could be the cause of the fires. Ranching using sown pastures has previously been referred to as a direct cause of forest loss in Bolivia (References 2 and 3). The Bolivian National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology (SENAMHI) issued high wind alerts in July and August for southern Bolivia, which could have led to the expansion of poorly managed fires. Also, August is usually the driest month of the year in this region. These conditions could explain the origin (poor fire practice) and expansion (little rain and strong winds) of the current fires.

Zooms B, C, E, F, G: Western Brazilian Amazon

The major fires in western Brazil seem to be at the agriculture-forest boundary. Note that Zoom B shows fire in a protected area in Amazonas state; Zoom C seems to show fire escaping (or deliberately set) in the primary forests in Rondonia state; and Zooms F and G seems to show fire expanding plantation into forest in Amazonas and Mato Grosso states, respectively.

Zoom D: Southern Peruvian Amazon

Fires burning forest near the town of Iberia, an area along the Interoceanic Highway that has become a deforestation hotspot in the region of Madre de Dios (see MAAP #28 and MAAP #47).

Additonal References

We have these to be some of the most informative additional references:

Technical References

1 Müller, R., T. Pistorius, S. Rohde, G. Gerold & P. Pacheco. 2013. Policy options to reduce deforestation based on a systematic analysis of drivers and agents in lowland Bolivia. Land Use Policy 30(1): 895-907. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. landusepol.2012.06.019

2 Muller, R., Larrea-Alcázar, D.M., Cuéllar, S., Espinoza, S. 2014. Causas directas de la deforestación reciente (2000-2010) y modelado de dos escenarios futuros en las tierras bajas de Bolivia. Ecología en Bolivia 49: 20-34.

3 Müller, R., P. Pacheco & J. C. Montero. 2014. El contexto de la deforestación y degradación de los bosques en Bolivia: Causas, actores e instituciones. Documentos Ocasionales CIFOR 100, Bogor. 89 p.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Beavers, D. Larrea, T. Souto, M. Silman, A. Condor, and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: MacArthur Foundation, International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Citation

Novoa S, Finer M (2019) Seeing the Amazon Fires with Satellites. MAAP: 107.

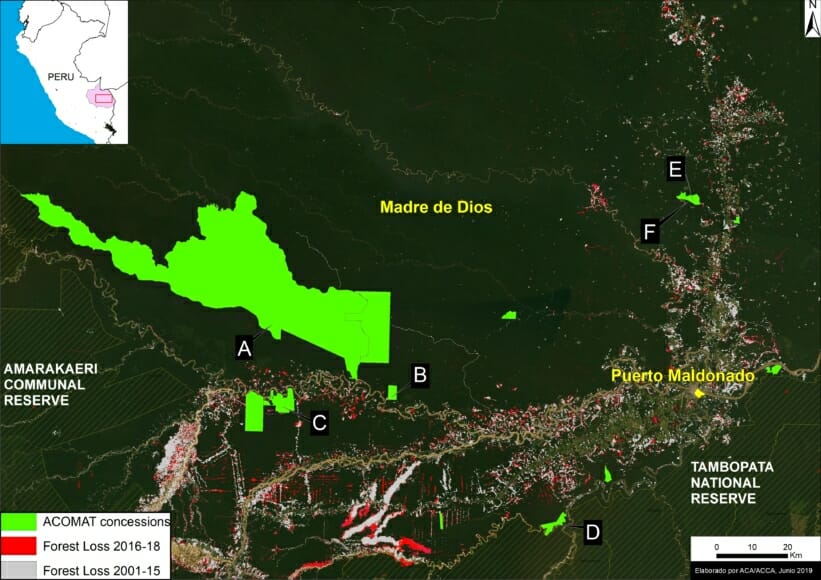

MAAP #105: From satellite to drone to legal action in the Peruvian Amazon

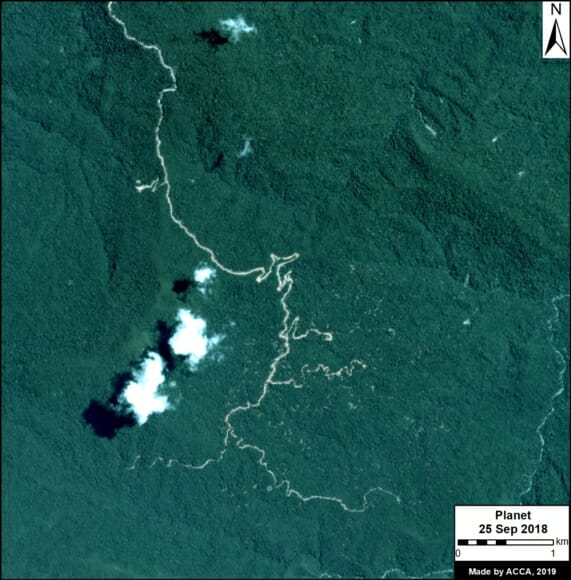

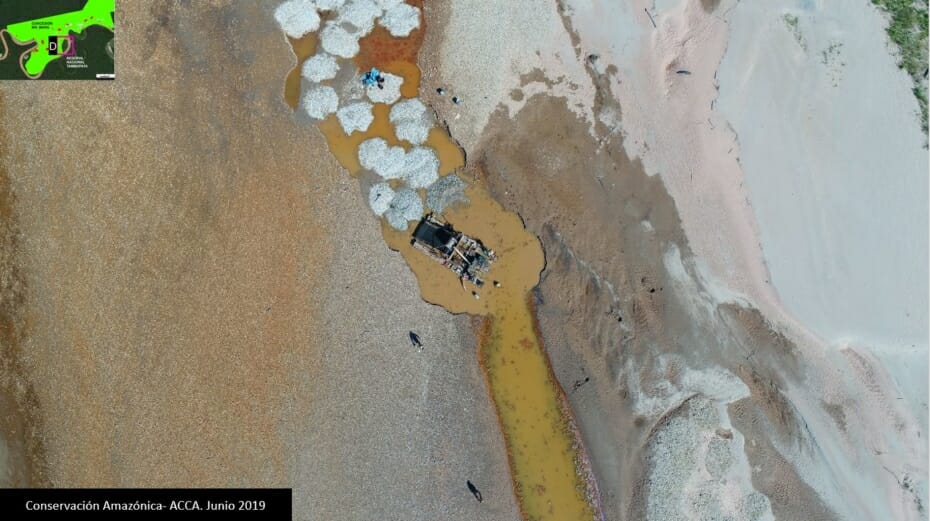

Amazon Conservation, in collaboration with its Peruvian sister organization, is implementing a project aimed at linking cutting-edge technology (satellites and drones) with legal action, in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region).

The project is building a comprehensive deforestation monitoring system with a local group of forestry concessionaires, known as ACOMAT,* who manage over 486,000 acres (see Base Map).

The monitoring system has three basic steps:

1) Real-time deforestation monitoring with satellite-based early warning forest loss alerts.*

2) Verify and document the alerts with drone overflights.*

3) Initiate a criminal complaint with the local environmental prosecuter’s office* (or an administrative complaint with the relevant forestry authorities) if suspected illegalities are found.

Below, we describe 6 cases (A-E) that have been generated from this comprehensive monitoring system.

It is important to emphasize that this type of monitoring system, featuring local forest custodians (such as concessionaires and indigenous communities) is possible to replicate in the Amazon and other tropical forests.

This innovative project is largely funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) and International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC).

Case A. Illegal logging in the “Los Amigos” Conservation Concession

This evidence in this case was obtained from a drone overflight of an area that was the subject of an early warning forest loss alert within Los Amigos Conservation Consession (a conservation area where logging is not permitted). The overflight documented the illegal logging of the timber species known locally as tornillo (Cedrelinga cateniformis) within the concession (see image below). The drone images were presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office in Madre de Dios as part of a criminal complaint.

Case B. Illegal mining in the “Sonidos de la Amazonía” Ecotourism Concession

The owner of the Sonidos de la Amazonía Ecotourism Concession received an early warning forest loss alert on his cellphone. She then organized a drone overflight and documented active illegal gold mining activity, including infrastructure (see image below). The drone images were presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office in Madre de Dios as part of a criminal complaint.

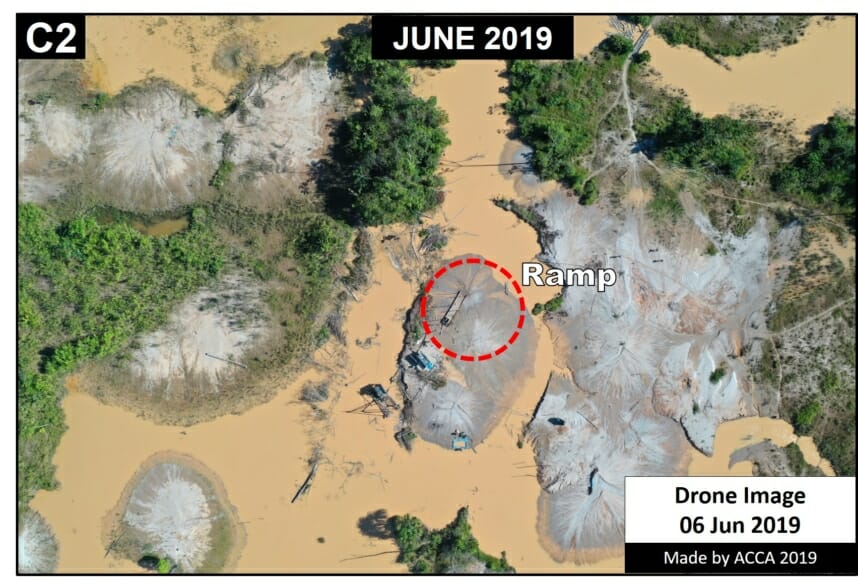

Case C. Illegal mining in the “AGROFOCMA” Forestry Concession

The owner of the AGROFOCMA forestry (logging) concession received an early warning forest loss alert on his cellphone. He then organized a drone overflight and documented active illegal gold mining activity, including infrastructure (see image below). The drone images were presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office in Madre de Dios as part of a criminal complaint.

Case D. Illegal mining in the “Inversiones Manu” Forestry Concession

The owner of the Inversiones Manu forestry (logging) concession received an early warning forest loss alert on his cellphone. He then organized a drone overflight and documented active illegal gold mining activity, including workers and infrastructure (see image below). The drone images were presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office in Madre de Dios as part of a criminal complaint.

Case E. Illegal logging in the “Sara Hurtado” Brazil Nut Concession

The owner of the Sara Hurtado Brazil Nut Concession received an early warning forest loss alert on her cellphone. She then organized a drone overflight and documented active illegal logging activity, including cedar wood planks (see image below). The drone images were presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office in Madre de Dios as part of a criminal complaint.

In a related case, drones also captured images of a nearby collection center and transport truck for the recently logged planks. These images were also presented to the environmental prosecuter’s office as part of a sixth case.

*Notes

ACOMAT is the “Asociación de Concesionarios Forestales Maderables y no Maderables de las Provincias del Manu, Tambopata y Tahuamanu.”

The early warning alerts are generated by the Peruvian government (Geobosques/MINAM). GLAD alerts can also be used (these are generated by the University of Maryland and presented by Global Forest Watch). In our case, the concessionaires receive Geobosques alerts in their emails.

We used quadricopter drones. Obtained images are very-high resolution (<5 cm).

The local environmental prosecuter’s office is the “Fiscalía Especializada en Materia Ambiental (FEMA) de Madre de Dios.”

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Novoa (ACCA), H. Balbuena (ACCA), E. Ortiz (AAF), T. Souto (ACA), P. Rengifo (ACCA), A. Condor (ACCA), y G. Palacios for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this report.

This work supprted by the following funders: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), MacArthur Foundation, Metabolic Studio.

Citation

Guerra J, Finer M, Novoa S (2019) From satellite to drone to legal action in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 105.

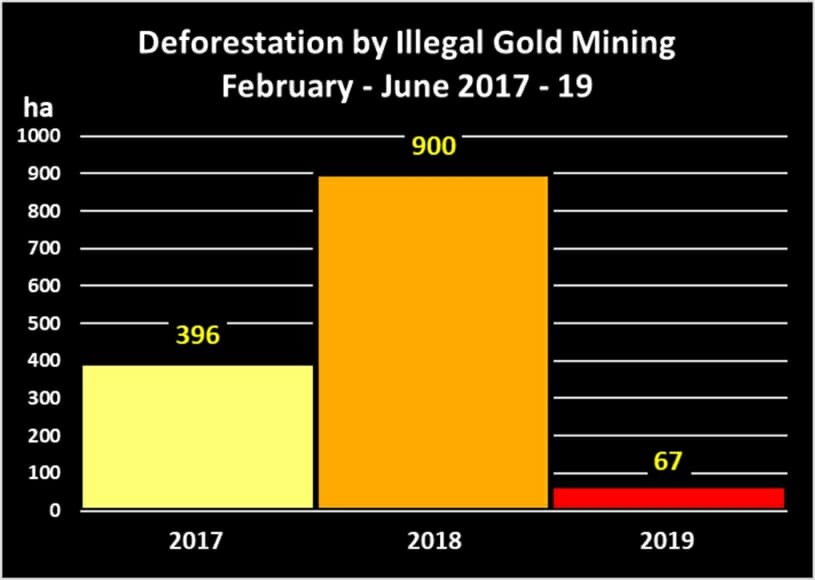

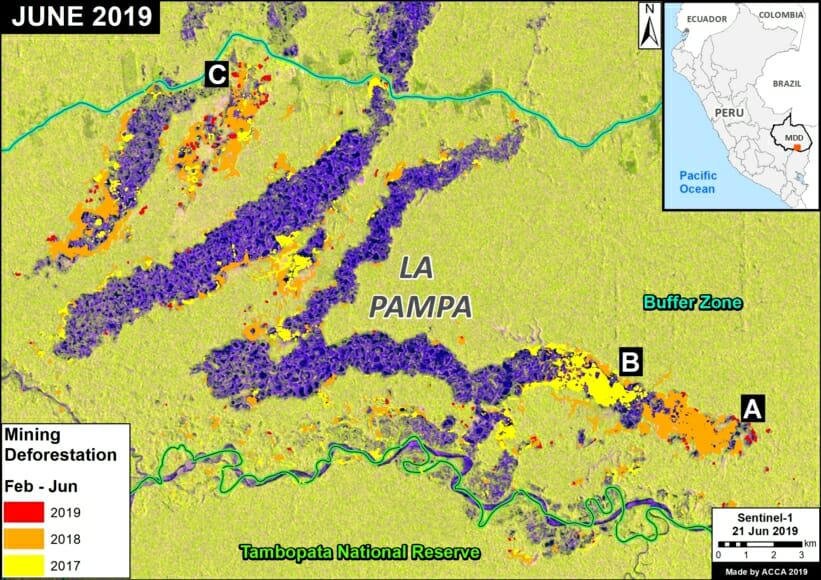

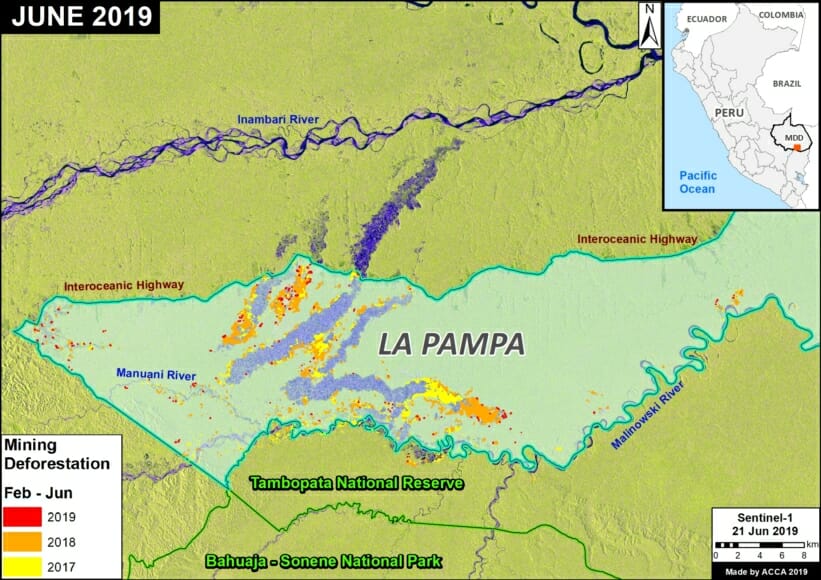

MAAP #104: Major Reduction in Illegal Gold Mining from Peru’s Operation Mercury

In February 2019, the Peruvian government launched Operation Mercury (Operación Mercurio), a major multi-sectoral crackdown on the illegal gold mining crisis in the area known as La Pampa,* located in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region). Note that this area is not within Tambopata National Reserve, but in its buffer zone.

In this report, we present the results of our analysis on the initial impacts of this Operation.

We found a major reduction in gold mining deforestation in La Pampa in 2019, compared to the same time period (February – June) of the previous two years (see Graph 1).

In fact, the gold mining deforestation decreased 92% between 2018 (900 hectares) and 2019 (67 hectares), representing the situation before and after the start of Operation Mercury.

The Base Map illustrates how the expansion of gold mining deforestation greatly dropped in 2019 compared to the two previous years, especially in the eastern front. The letters (A-C) correspond to the location of the Zooms, below.

The analysis also reveals, however, that the gold mining deforestation in La Pampa has not yet been completely eradicated and continues in numerous remote and isolated areas.

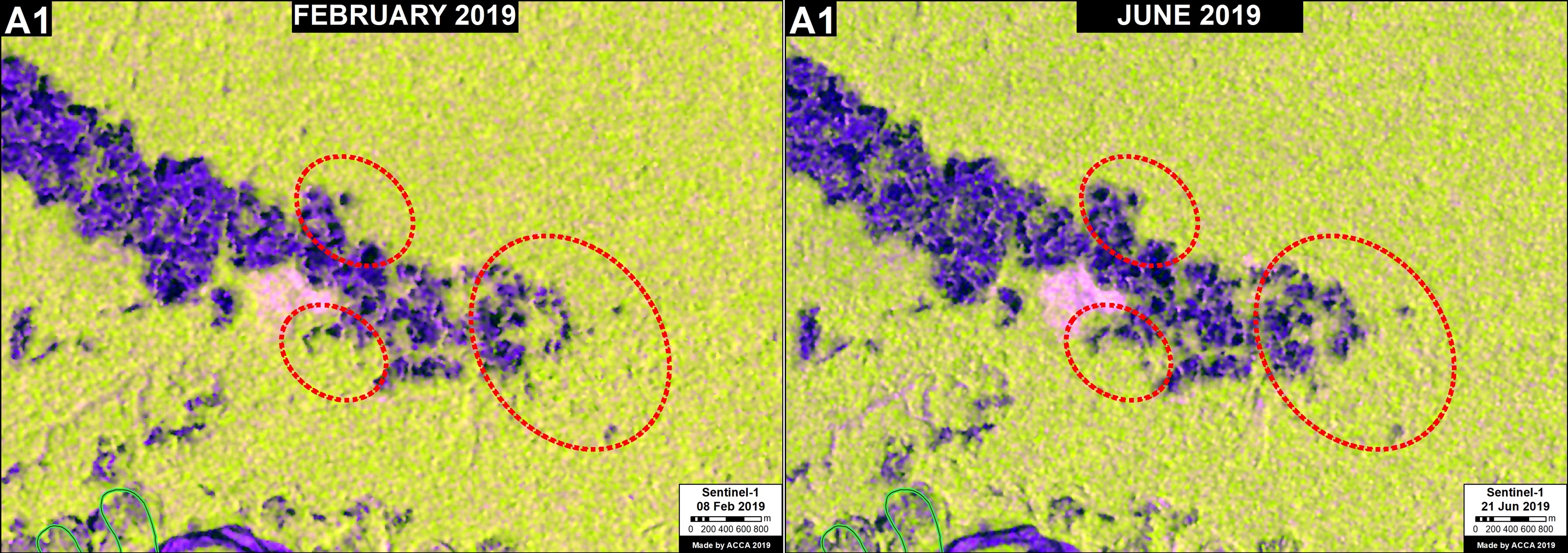

Zoom A1 shows the critical eastern front of the gold mining deforestion between February (left panel) and June (right panel) 2019, the first five months of Operation Mercury. While the rapid eastward expansion of the front has greatly decreased, the red circles indicate areas where we have detected isolated mining activity.

High Resolution Zooms

Zoom B shows the eradication of one of the biggest mining camps in La Pampa between 2018 (left panel) and 2019 (right panel).

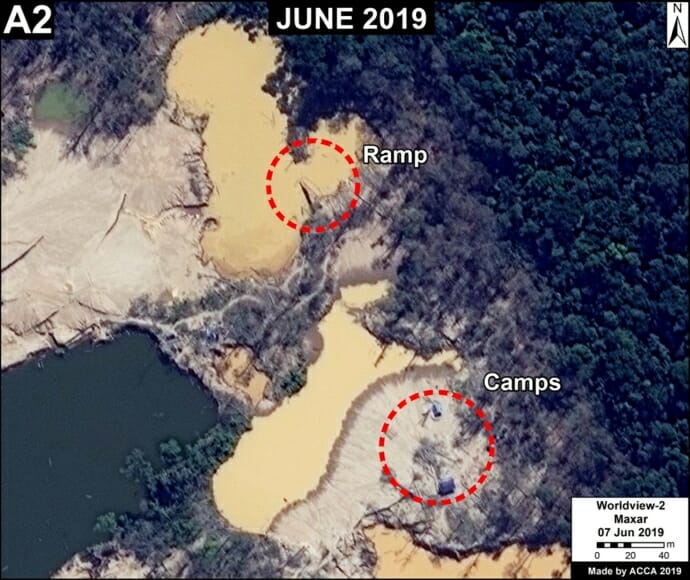

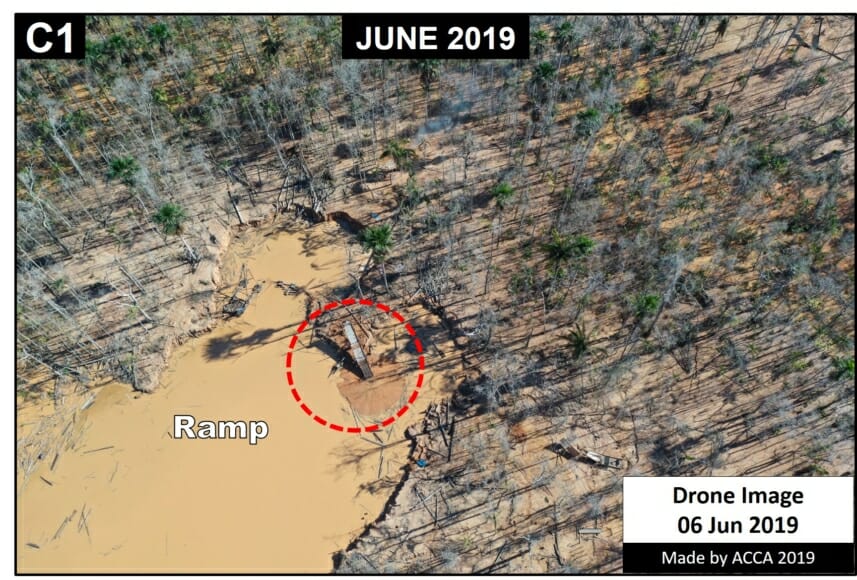

The following Zooms show examples of the persistence of isolated illegal gold mining activity and infrastructure in La Pampa, with recent (June 2019) high resolution satellite and drone images. The letters (A2, C1, C2) correspoind to the Base Map, above.

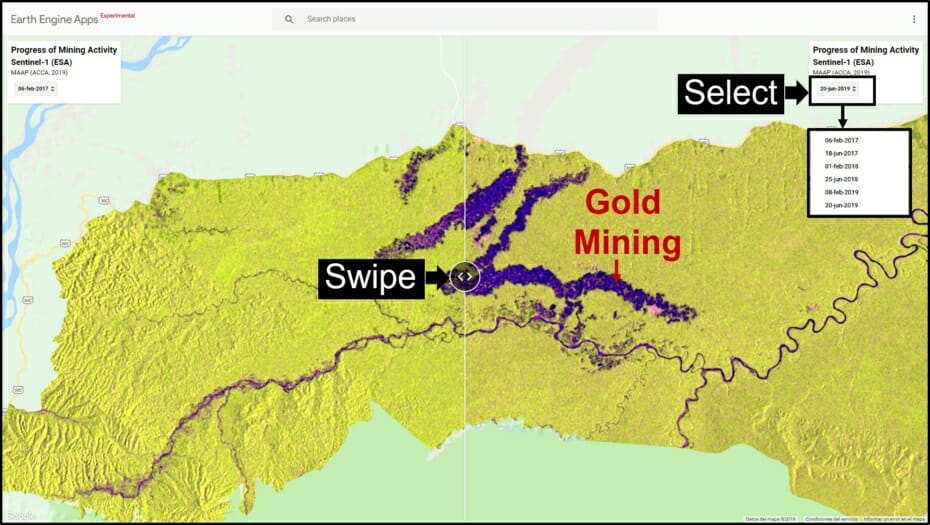

Google Earth Engine App

We present a new app, developed with Google Earth Engine, that allows an interactive visualization of the evolution of gold mining deforestation in La Pampa. The app allows the user to take advantage of Google’s powerful computers to compare (with a slider) different dates from a large archive of Sentinel-1 satellite images (see screenshot, below). Sentinel-1 is radar, so there are no clouds in the images.

https://luciovilla.users.earthengine.app/view/mining-monitoring-by-sar-sentinel-1

Notes

*La Pampa is the sector located in the buffer zone of Tambopata National Reserve, delimited by the northern boundary of the reserve, the Malinowski River and the Interoceanic Highway.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Novoa (ACCA), H. Balbuena (ACCA), E. Ortiz (AAF), T. Souto (ACA), P. Rengifo (ACCA), A. Condor (ACCA), y G. Palacios for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this report.

This work supprted by the following funders: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), MacArthur Foundation, Metabolic Studio, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Citation

Villa L, Finer M (2019) Major Reduction in Illegal Gold Mining from Peru’s Operation Mercury. MAAP: 104.

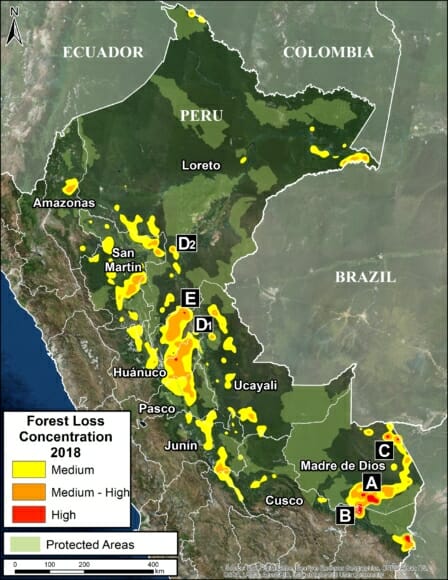

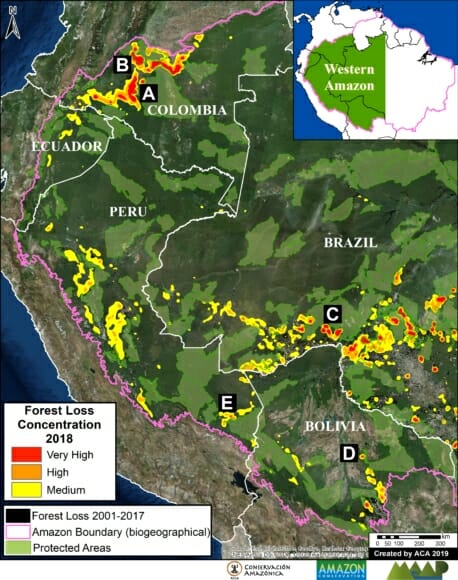

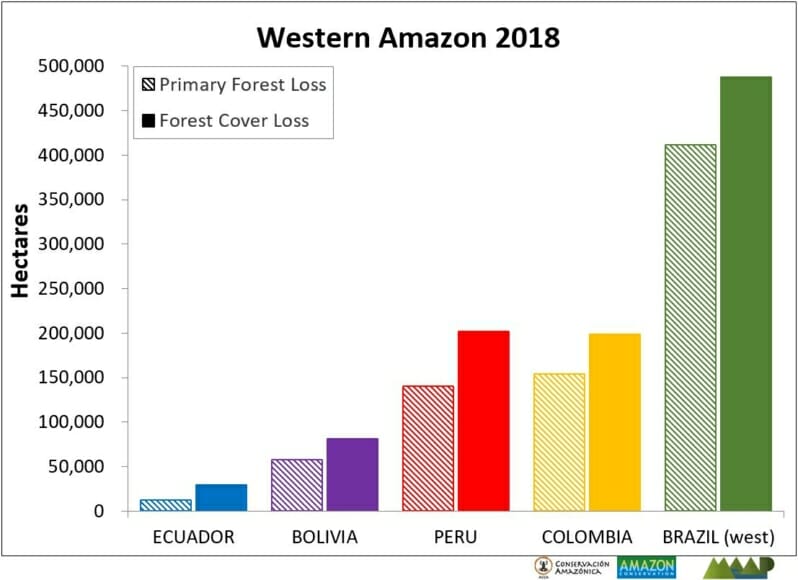

MAAP #100: Western Amazon – Deforestation Hotspots 2018 (a regional perspective)

For the 100th MAAP report, we present our first large-scale western Amazon analysis: Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, and western Brazil (see Base Map).

We use the new 2018 data for forest cover loss, generated by the University of Maryland (Hansen et al 2013) and presented by Global Forest Watch.

These data indicate 2.5 million acres of forest cover loss in the western Amazon in 2018.*

We conducted an additional analysis that indicates, of this total, 1.9 million acres were primary forest.*

To identify deforestation hotspots consistently across this vast landscape, we conducted a kernel density analysis (see Methodology).

The Base Map shows the hotspots in yellow, orange and red, indicating areas with medium, high, and very high forest loss concentrations, respectively.

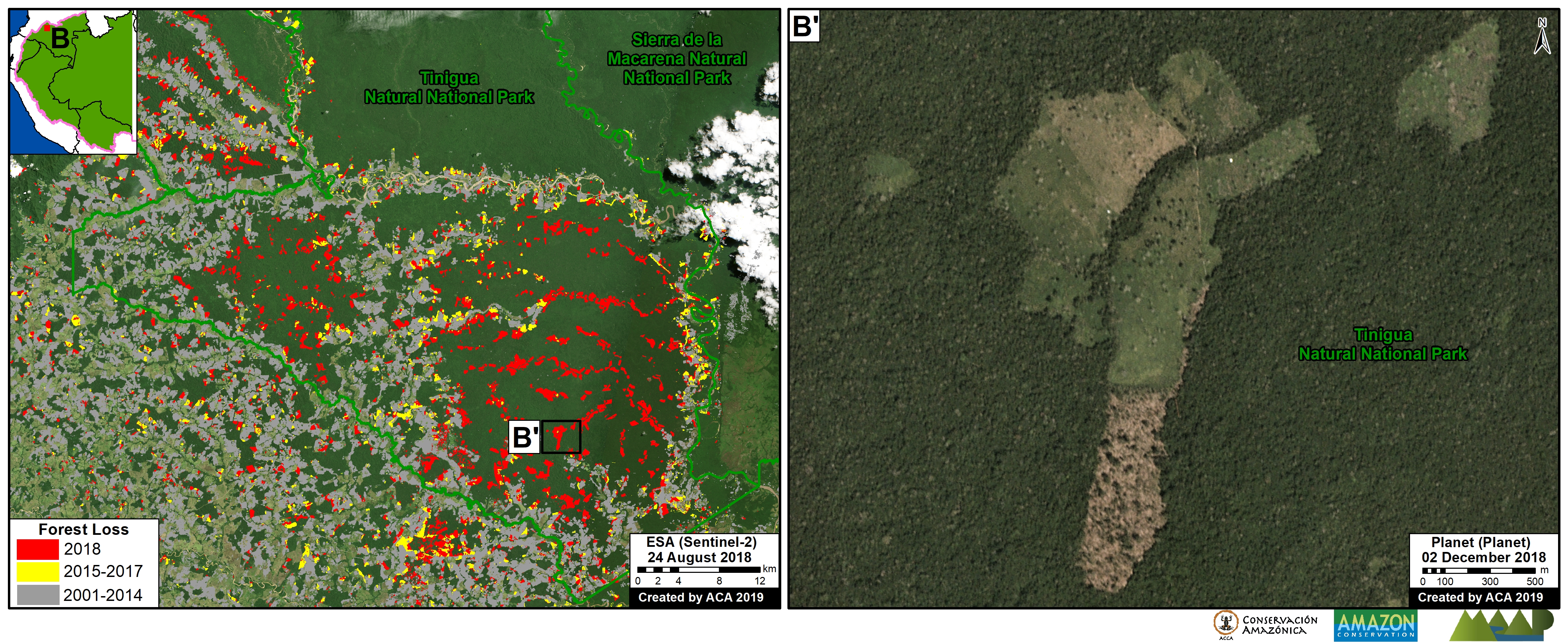

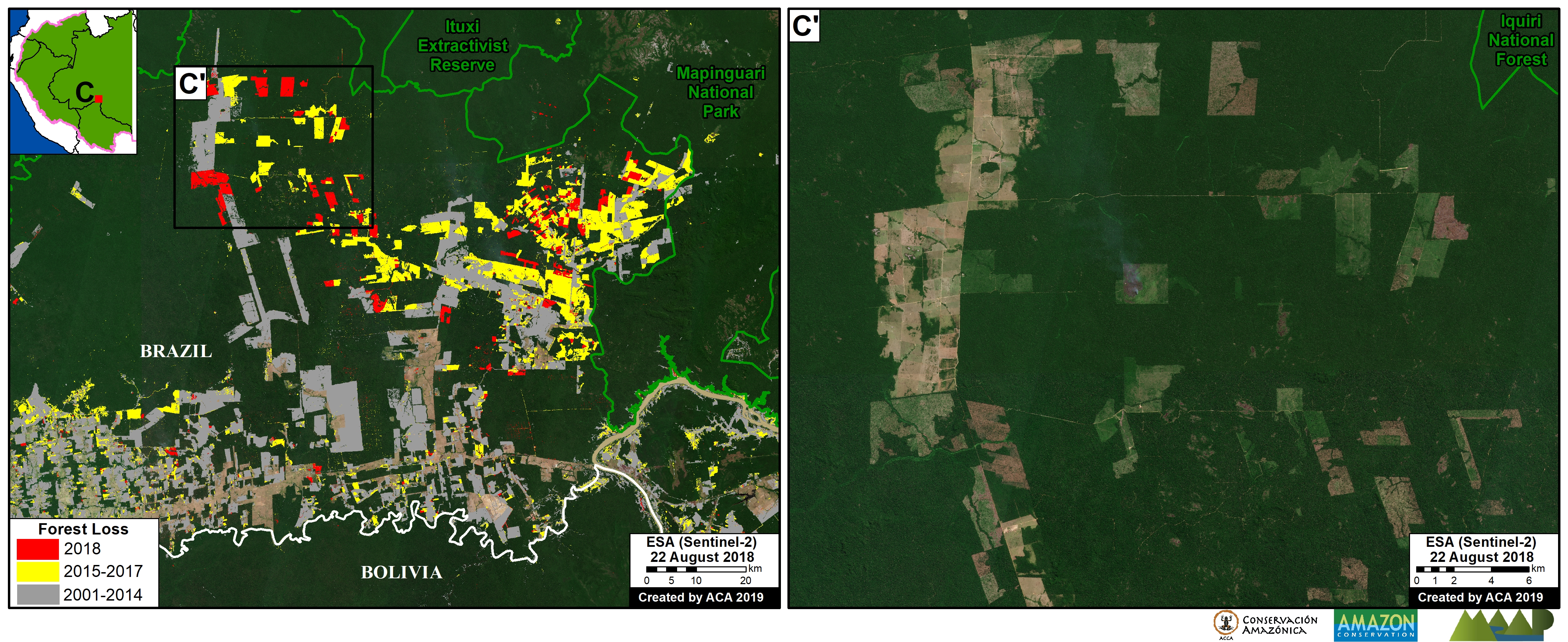

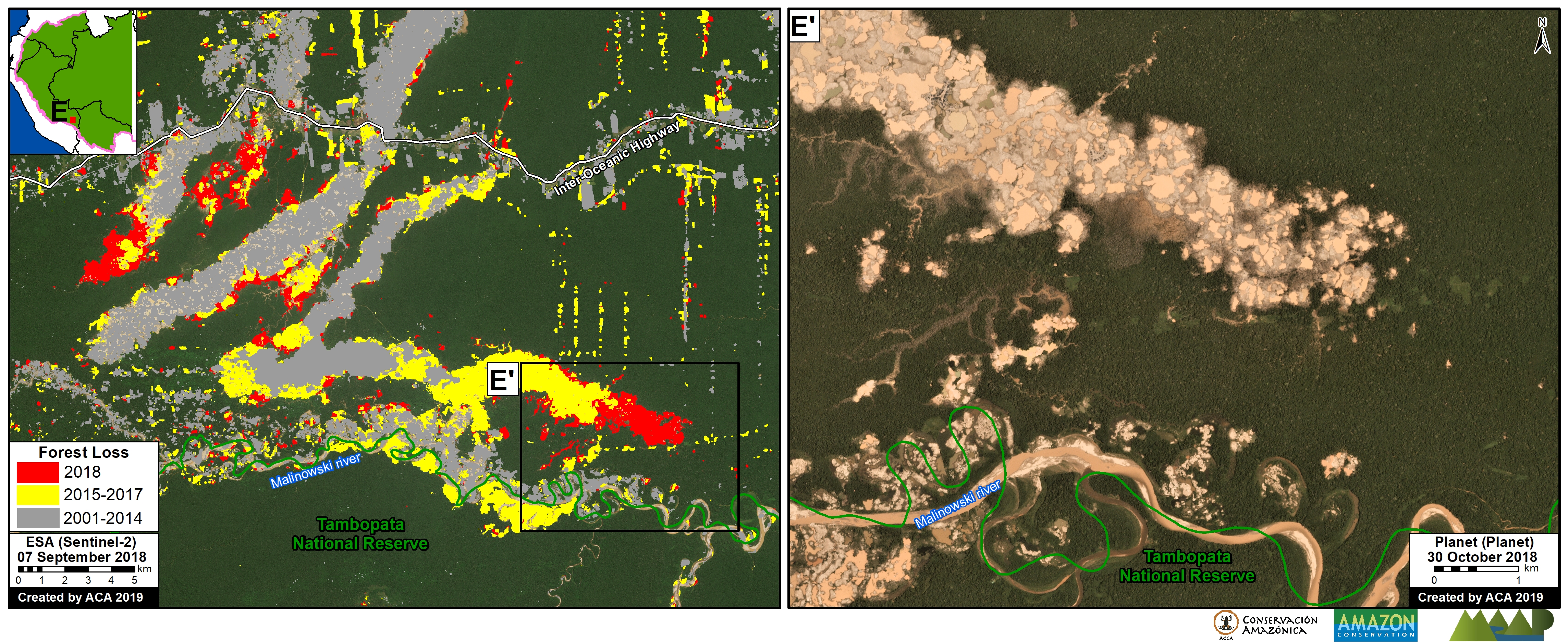

Next, we focus on five zones of interest (Zooms A-E) in Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru. For all images, please click to enlarge.

*Forest Cover Loss: 5 acres per minute. Almost half (49%) occurred in Brazil, followed by Peru (20%), Colombia (20%), Bolivia (8%), and Ecuador (3%). see Annex.

**Primary Forest Loss: 3.5 acres per minute. Over half (53%) occurred in Brazil, followed by Peru (20%), Colombia (18%), Bolivia (7%), and Ecuador (2%). see Annex.

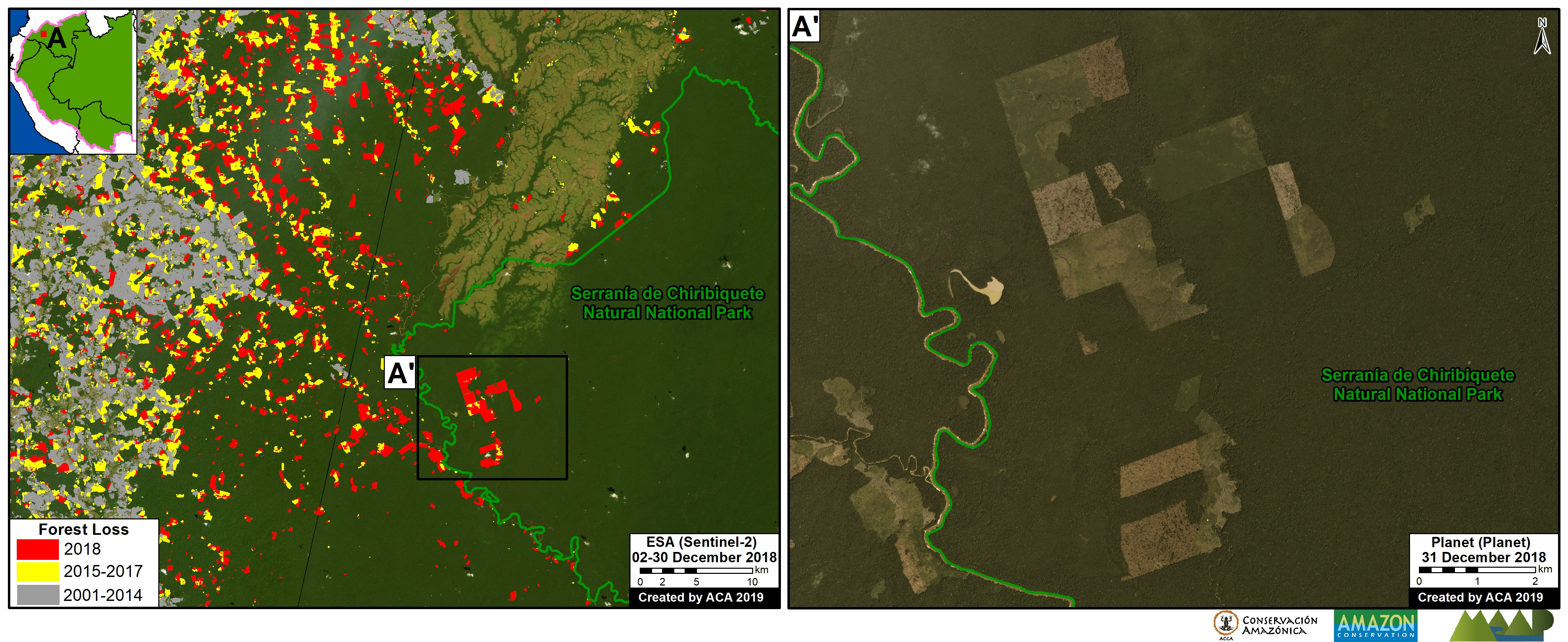

Colombia

The largest concentration of 2018 forest loss is in the northeast Colombian Amazon (494,000 acres). Out of this total, 11% (56,800 acres) occurred in national parks. National experts indicate that land grabbing has emerged as a leading direct driver of deforestation (Arenas 2018). See MAAP #97 for more information.

Zoom A shows the forest loss expanding towards western Chiribiquete National Park, including distinct deforestation in this protected area during 2018.

Zoom B shows the extensive 2018 deforestation (30,000 acres) within Tinigua National Park. A recent news report indicates that cattle ranching is one of the factors related to this deforestation.

Brazil (border with Bolivia)

Another important result is the contrast between northern Bolivia (Pando department) and adjacent side Brazil (states of Acre, Amazonas, and Rondônia). Zoom C shows several deforestation hotspots on the Brazilian side, while the Bolivian side is much more intact.

Bolivia

In Bolivia, the major forest loss hotspots are further south. Zoom D shows the recent deforestation (5,000 acres in 2018) due to agricultural activity associated with one of the first major Mennonite settlements in Beni department (Kopp 2015). The other Mennonite settlements are located further south.

Peru

The Hansen data indicates over 200,000 acres of forest loss during 2018 in the Peruvian Amazon. One of the most important deforestation drivers, especially in southern Peru, is gold mining. We estimate 23,000 acres of gold mining deforestation during 2018 in the southern Peruvian Amazon (see MAAP #96).

Zoom E shows the most emblematic case of gold mining deforestation: the area known as La Pampa.

It is important to emphasize, however, that in February 2019 the Peruvian government launched “Operation Mercury 2019” (Operación Mercurio 2019), a multi-sectoral and comprehensive mega-operation aimed at eradicating illegal mining and associated crime in La Pampa, as well as promote development in the region.

Annex

Methods

The 2018 forest loss data presented in this report were generated by the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) laboratory at the University of Maryland (Hansen et al 2013) and presented by Global Forest Watch. Our study area is strictly what is presented in the Base Map: the areas within the Amazonian biogeographic boundary of the western Amazon.

Specifically, for our estimate of forest cover loss, we multiplied the annual “forest cover loss” data by the density percentage of the “tree cover” from the year 2000 (values >30%).

For our estimate of primary forest loss, we intersected the forest cover loss data with the additional dataset “primary humid tropical forests” as of 2001 (Turubanova et al 2018). For more details on this part of the methodology, see the Technical Blog from Global Forest Watch (Goldman and Weisse 2019).

All data were processed under the geographical coordinate system WGS 1984. To calculate the areas in metric units the UTM (Universal Transversal Mercator) projection was used: Peru and Ecuador 18 South, Colombia 18 North, Western Brazil 19 South and Bolivia 20 South.

Lastly, to identify the deforestation hotspots, we conducted a kernel density estimate. This type of analysis calculates the magnitude per unit area of a particular phenomenon, in this case forest cover loss. We conducted this analysis using the Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGIS. We used the following parameters:

Search Radius: 15000 layer units (meters)

Kernel Density Function: Quartic kernel function

Cell Size in the map: 200 x 200 meters (4 hectares)

Everything else was left to the default setting.

For the Base Map, we used the following concentration percentages: Medium: 10%-20%; High: 21%-35%; Very High: >35%.

References

Arenas M (2018) Acaparamiento de tierras: la herencia que recibe el nuevo gobierno de Colombia. Mongabay, 2 AGOSTO 2018. https://es.mongabay.com/2018/08/acaparamiento-de-tierras-colombia-estrategias-gobierno/

Goldman L, Weisse M (2019) Technical Blog: Global Forest Watch’s 2018 Data Update Explained. https://blog.globalforestwatch.org/data-and-research/blog-tecnico-explicacion-de-la-actualizacion-de-datos-de-2018-de-global-forest-watch

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from: http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest.

Kopp Ad (2015) Las colonias menonitas en Bolivia. Tierra. http://www.ftierra.org/index.php/publicacion/libro/147-las-colonias-menonitas-en-bolivia

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Turubanova S., Potapov P., Tyukavina, A., and Hansen M. (2018) Ongoing primary forest loss in Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aacd1c

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Terán (ACEAA), M. Weisse (GFW/WRI), A. Thieme (UMD), R. Catpo (ACCA) and A. Cóndor (ACCA) for helpful comments to this report.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2019) Western Amazon – Deforestation Hotspots 2018 (a regional perspective). MAAP: 100.

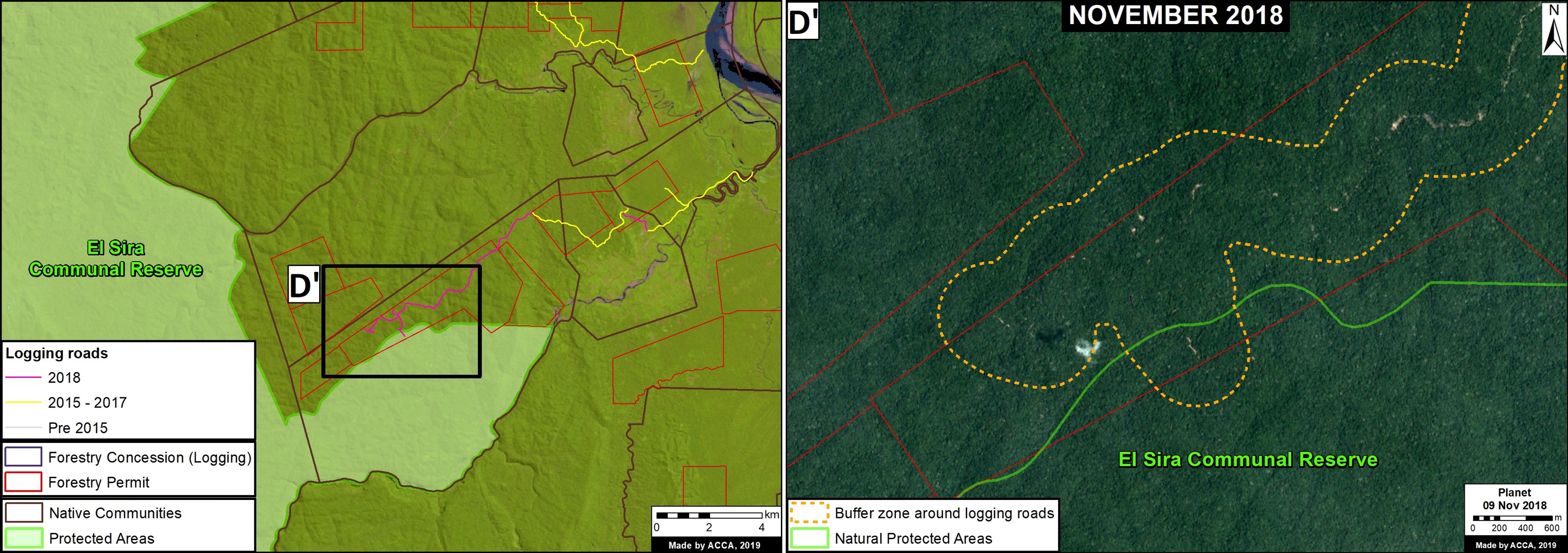

MAAP #99: Detecting Illegal Logging in the Peruvian Amazon

In the Peruvian Amazon, most of the logging is selective (not clearcutting), with the targets being higher-value species. Thus, illegal logging is difficult to detect with satellite imagery.

In MAAP #85, however, we presented the potential of satellite imagery in identifying logging roads, which are one of the main indicators of logging activity in the remote Amazon.

Here, we go a step further and show how to combine logging road data with additional land use data, such as forestry licenses and concessions, to identify possible illegal logging.

This analysis, based in the Peruvian Amazon, has two parts. First, we identify the construction of new logging roads in 2018, updating our previous dataset from 2015-17 (see Base Map).

Second, we analyze these new logging roads in relation to addition spatial information now available on government web portals,* in order to identify possible illegality.

*We analyzed information on several websites now available from national and regional authorities, such as SISFOR (OSINFOR), GEOSERFOR (SERFOR), and IDERs (Spatial Data Infrastructure of Regional governments). These new resources provide valuable information, however may have limitations in ability to constantly update information on the status of concessions and forest permits.

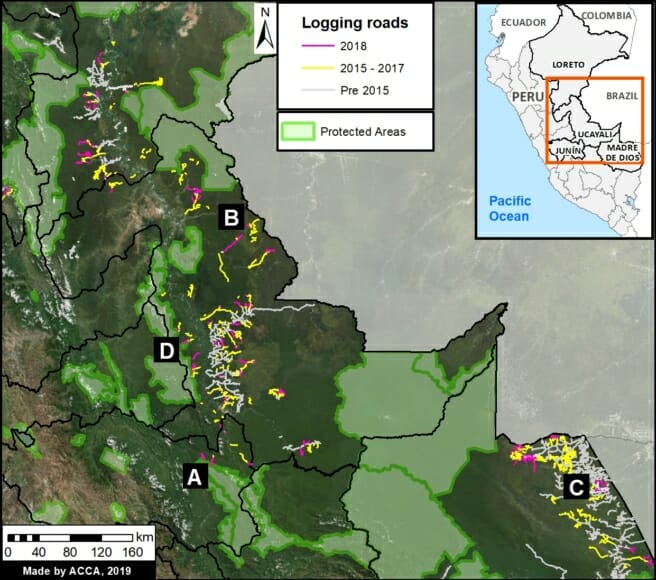

Base Map

The Base Map illustrates the precise location of logging roads built in the Peruvian Amazon over the last four years.

Previously (MAAP #85), we estimated the construction of 2,200 kilometers of logging roads during 2015-17 (yellow).

Here, we estimate the construction of an additional 1,100 km in 2018 (pink).

Thus, in total, we have documented the construction of 3,300 km of logging roads over the last four years (2015-18).

Note that these logging roads are concentrated mainly in the regions of Ucayali, Madre de Dios (northeast), and Loreto (south).

Cases of Possible Illegal Logging

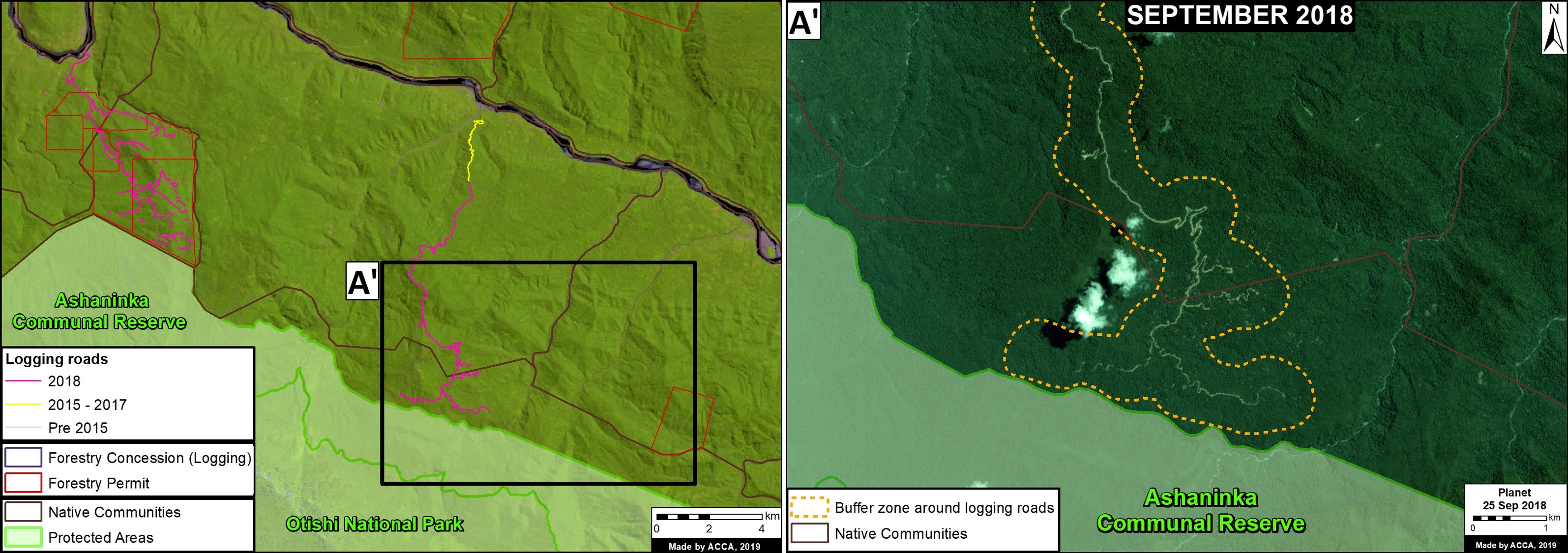

A. Logging roads in non-forestry areas

Zoom A shows the construction of a logging road past the border of a forestry permit, into a non-forestry area. In this case, the road extends close (200 meters) to the border of a protected area (Ashaninka Communal Reserve). It is important to point out that this type of analysis requires frequently updated information from the entities that grant forest permits, such as regional governments.

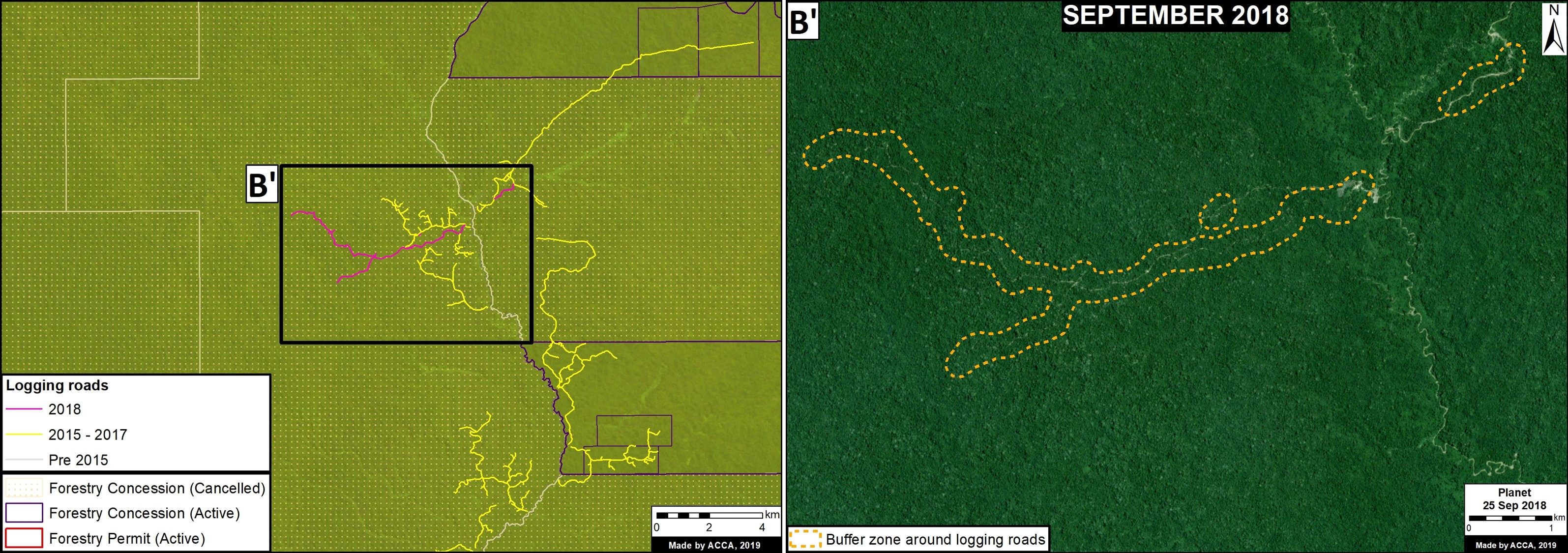

B. Logging roads in canceled concessions

Zoom B shows the construction of logging roads within logging concessions classified as “Caducado,” or cancelled (no longer active). This type of analysis also requires frequently updated information on the status of forestry concessionaries.

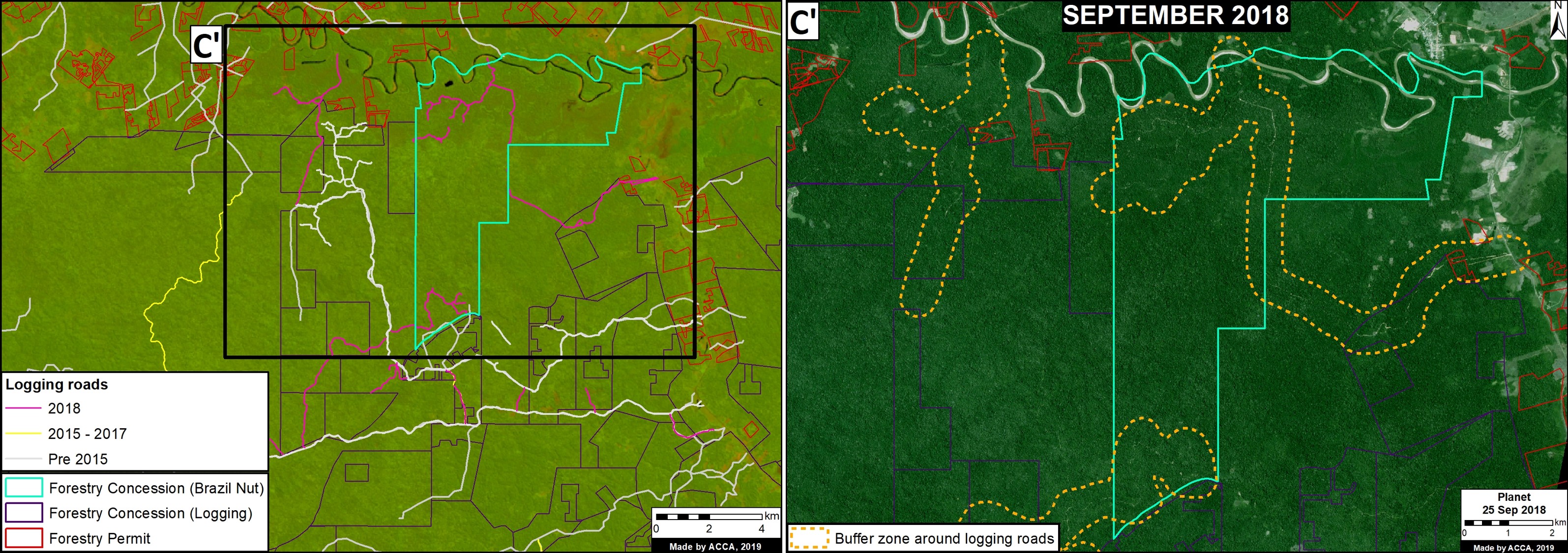

C. Logging Roads in Brazil nut concessions

Zoom C shows the construction of logging roads within a Brazil nut forestry concession. While some managed timber extraction is allowed in Brazil nut concessions, the extensive construction of two logging roads, along with the irregular logging area boundaries, drew attention. A detailed investigation by the Peruvian Forestry Service (SERFOR) and environmental prosecutor (FEMA) revealed the illegality of this logging activity (see this article from Mongabay for more information).

D. Logging roads in protected areas

Zoom D shows part of a logging road entering a protected area (El Sira Communal Reserve). It appears that this section of the reserve overlaps with a forestry permit obtained after the creation of the protected area. It is worth emphasizing that according to Peruvian law, timber extraction is not permitted within protected areas such as El Sira.

SERNANP (the Peruvian National Service of Natural Protected Areas) has communicated these facts to the region of Ucayali’s Provincial Prosecutor’s Office Specialized in Environment (Atalaya headquarters). Also, SERNANP is managing the process of nullifying the permit, given that it doesn’t have the technical opinion of SERNANP, a requirement as stated by the current regulation.

References

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Acknowledgments

We thank OSINFOR, SERNANP Alfredo Cóndor (ACCA) and Lorena Durand (ACCA) for helpful comments to this report.

Citation

Villa L, Finer M (2019) Detecting Illegal Logging in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 99.

MAAP #98: Deforestation Hotspots in the Peruvian Amazon, 2018

Thanks to early warning forest loss alerts,* we are able to make an initial assessment of the 2018 deforestation hotspots in the Peruvian Amazon.

The Base Map highlights the medium (yellow) to high (red) hotspots. In this context, hotspots are the areas with the highest density of forest loss alerts.

Note that the most intense hotspots are concentrated in the southern Peruvian Amazon, particularly the Madre de Dios region. In previous years, intense hotspots were also concentrated in the central Peruvian Amazon.

Next, we focus on 5 hotspots of interest (Zooms A-E).

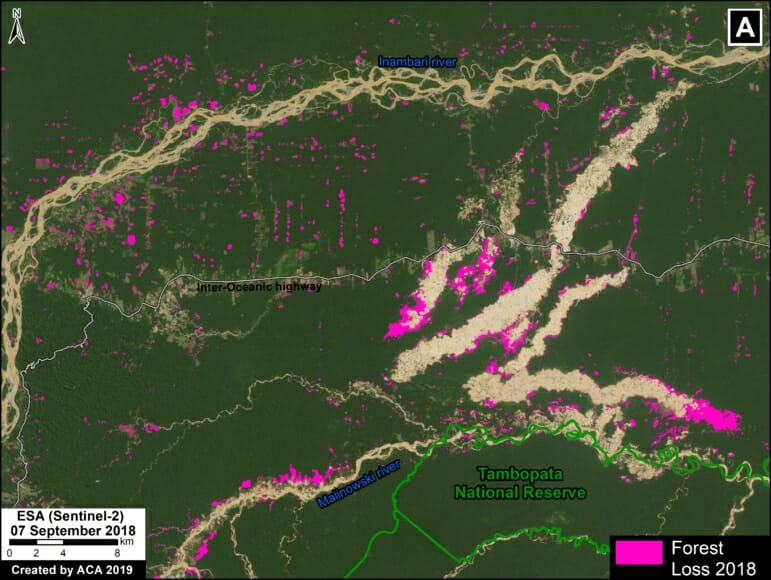

A. La Pampa (Madre de Dios)

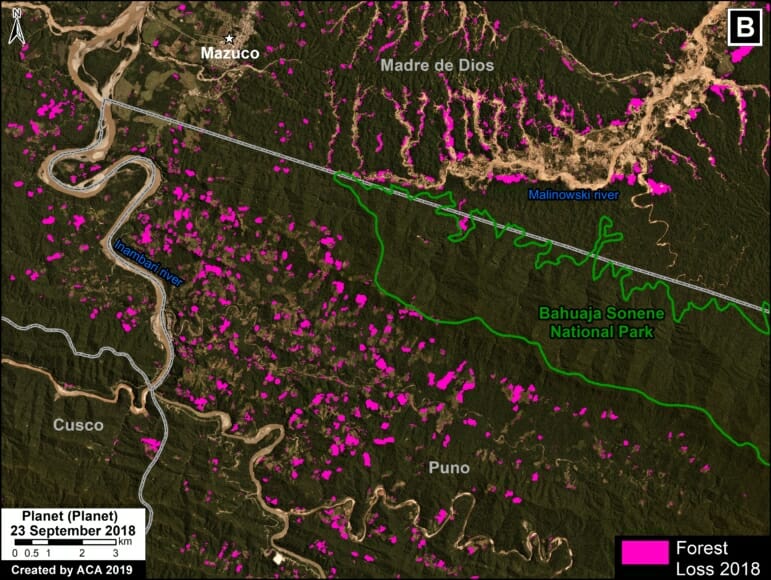

B. Bahuaja Sonene National Park (surroundings) (Madre de Dios, Puno)

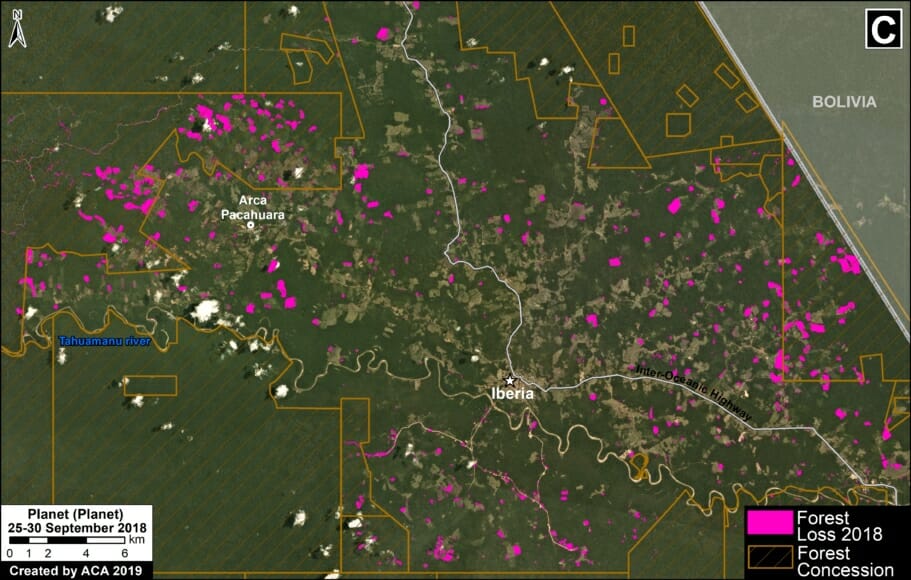

C. Iberia (Madre de Dios)

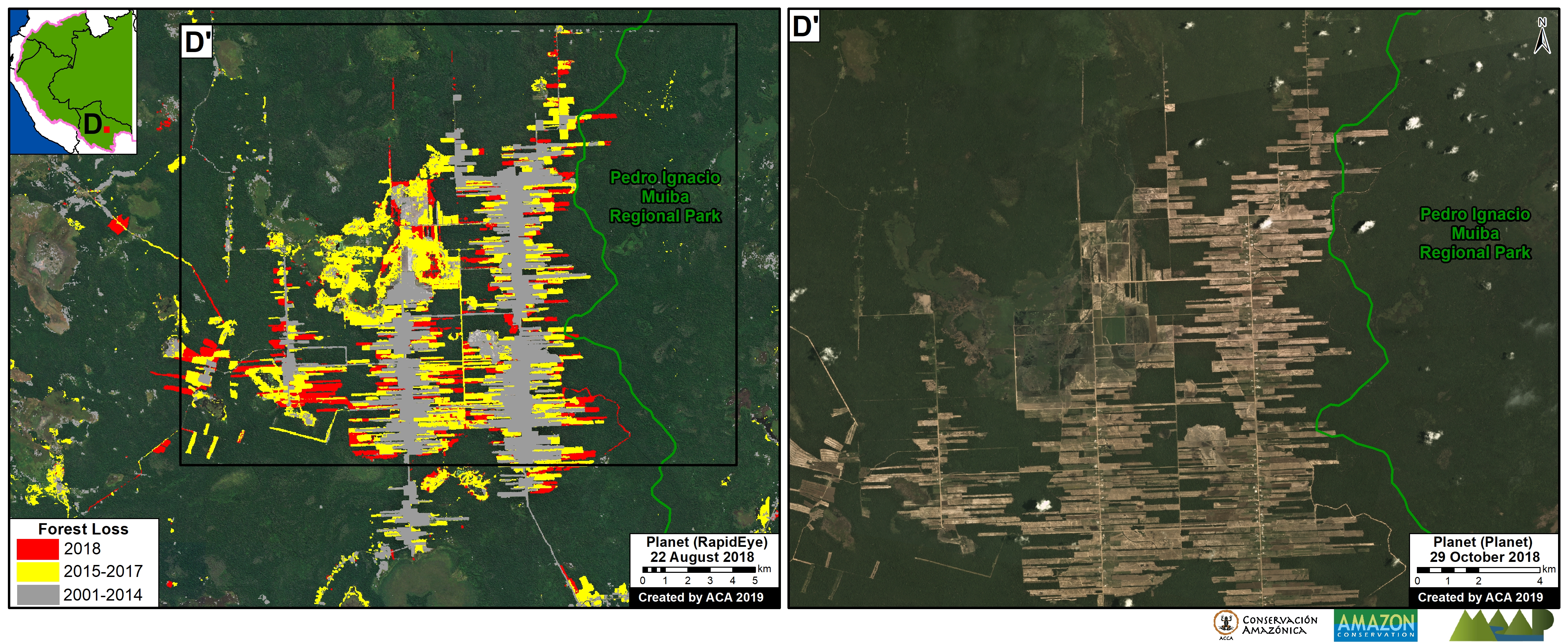

D. Organized Deforestation (Ucayali, Loreto)

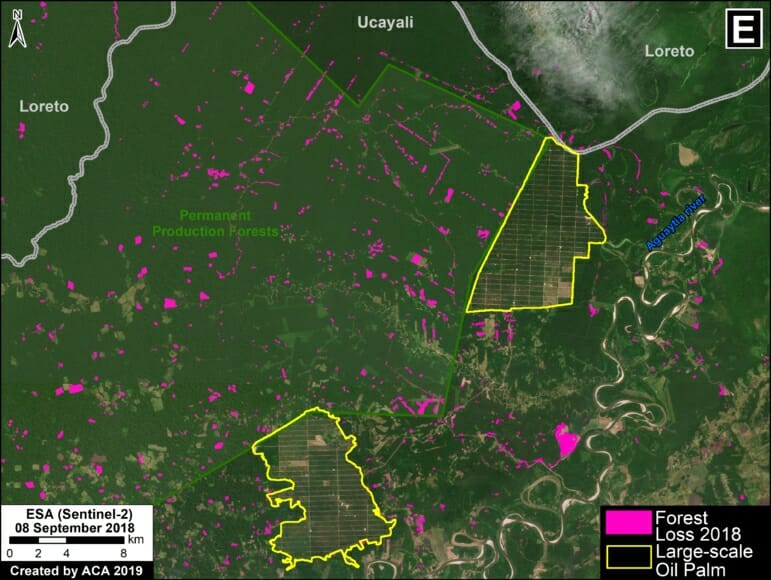

E. Central Amazon (Ucayali, Huánuco)

*The data presented in this report is an estimate based on early warning data generated by the National Program of Forest Conservation for the Mitigation of Climate Change of the Ministry of the Environment of Peru (PNCB/MINAM). We also analyzed University of Maryland GLAD alerts, obtained from Global Forest Watch.

A. La Pampa (Madre de Dios)

Zoom A shows two important cases in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region). First, gold mining deforestation south of the Interoceanic Highway in the area known as La Pampa. It is important to emphasize that the Peruvian government just started “Operation Mercury 2019” (Operación Mercurio 2019), a multi-sectoral and comprehensive mega-operation aimed at eradicating illegal mining and associated crime in La Pampa, as well as promote development in the region. Second, deforestation due to agricultural activity north of the highway. As in all the zoom maps below, pink indicates forest loss in 2018.

B. Bahuaja Sonene National Park (surroundings) (Madre de Dios, Puno)

Zoom B also shows two important cases in the southern Peruvian Amazon (regions of Madre de Dios and Puno), surrounding Bahuaja Sonone National Park. First, to the north of the park, is gold mining deforestation along the upper Malinowski River. The Peruvian protected areas agency (SERNANP) points out that they have limited the deforestation south of the river (direction towards the national park) due to their intensified patrols on that side. Second, to the south of the park, is non-mining (partly agricultural) deforestation.

C. Iberia (Madre de Dios)

Zoom C takes us to the other side of Madre de Dios, around the town of Iberia, near the border with Brazil and Bolivia. This area is experiencing extensive deforestation due to agricultural activity. There most intense deforestation is just of Iberia, where a religious community of farmers (Arca Pacahuara) is reportedly establishing large corn plantations (References 1-2). Much of the 2018 (and 2017) deforestation is occurring within forest concessions, where agriculture is not permitted.

D. Organized Deforestation (Ucayali, Loreto)

In 2018 we documented two similar cases in the central Peruvian Amazon. Both have similar forms of organized deforestation, characterized by what seems to be agricultural plots arranged along new access roads. Zoom D shows the Masisea case (left panel, zoom D1) and the Sarayaku case (right panel, zoom D2). See MAAP #92 for more information.

E. Central Amazon (Ucayali, Huánuco)

As in previous years, there was extensive deforestation in the central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali and Huánuco regions). Zoom E shows an example: small and medium-scale deforestation surrounding a pair of large-scale oil palm plantations. Some of the recent deforestation is occurring within “Permanent Production Forests,” forestry-zoned areas where agriculture is not permitted. This area also corresponds to the proposed territorial title of the indigenous Shipibo community of Santa Clara de Uchunya (see here for more information).

Methodology

We conducted this analysis using the Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGIS, using the following parameters:

Search Radius: 15000 layer units (meters)

Kernel Density Function: Quartic kernel function

Cell Size in the map: 200 x 200 meters (4 hectares)

Everything else was left to the default setting.

The data presented in this report is an estimate based on early warning data generated by the National Program of Forest Conservation for the Mitigation of Climate Change of the Ministry of the Environment of Peru (PNCB/MINAM). We also analyzed University of Maryland GLAD alerts, obtained from Global Forest Watch.

References

1. CIFOR 2016

2. GOREMAD 2016

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2018) Deforestation Hotspots in the Peruvian Amazon, 2018. MAAP: 98.

MAAP #96: Gold Mining Deforestation at Record High Levels in Southern Peruvian Amazon

Gold mining deforestation has been at record high levels in both 2017 and 2018 in the southern Peruvian Amazon.

Based on an analysis of nearly 500 high-resolution satellite images (from Planet and DigitalGlobe), we estimate the deforestation of 18,440 hectares across southern Peru during these last two years. That is equivalent to 45,560 acres (or 34,400 American football fields) in just two years.

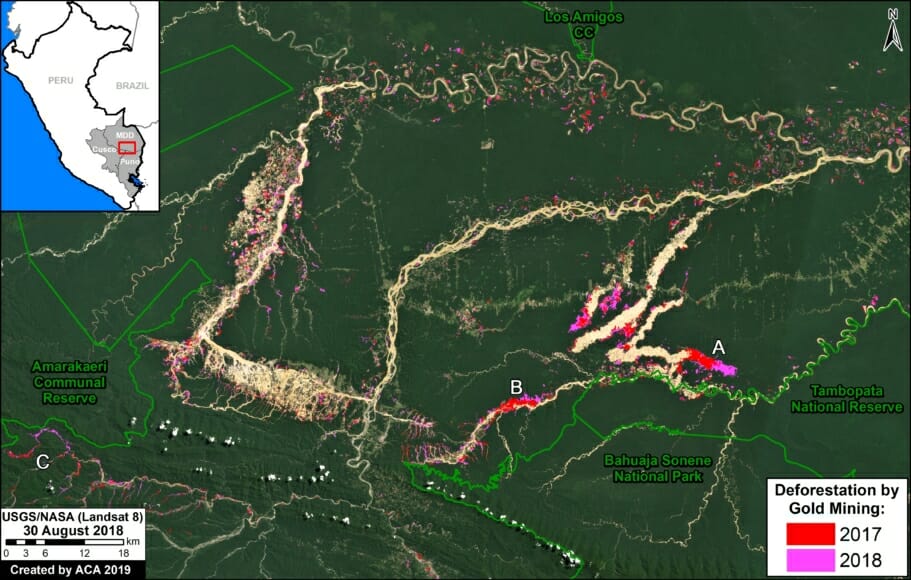

The Base Map highlights this recent deforestation, with 2017 in red and 2018 in pink. The Reference Map in Annex 1 shows our full study area.

2017 had the highest gold mining deforestation on record at the time: 9,160 hectares (22,635 acres). According to recent research led by CINCIA (Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica), this was the highest annual total on record dating back to 1985*.

In 2018, we found the gold mining deforestation was even higher: 9,280 hectares (22,930 acres).

Thus, combined, 2017-18 had the highest two-year deforestation total on record: 18,440 hectares (45,565 acres).

Note the location of Zooms (A-C) shown in greater detail below. These zooms represent three of the most threatened areas: A) La Pampa, B) Upper Malinowski, and C) Camanti.

Click (or right click) to enlarge (or download) images.

*CINCIA reports 9,860 hectares of gold mining deforestation in 2017 (CINCIA 2018, Caballero Espejo et al 2018), an estimate even higher than ours.

Zoom A: La Pampa

Image A shows the gold mining deforestation of 1,685 hectares (4,164 acres) between 2017 (left panel) and 2018 (right panel) in an area known as La Pampa (Madre de Dios region). Red indicates the major deforestation fronts.

As seen in the Land Use Map below (Annex 2), most of the recent mining deforestation in La Pampa is clearly illegal, concentrated in reforestation concessions and the buffer zone of Tambopata National Reserve.

According to the web portal GEOCATMIN (Geological Information System and Mining Register), developed by INGEMMET (Geological Mining and Metallurgical Institute of Peru), all titled mining concessions in the area are currently “without mining activity.” None are in authorized Exploration or Exploitation phase. Most of the mining activity is outside these concessions and in areas not authorized for mining.

Zoom B: Upper Malinowski

Image B shows the gold mining deforestation of 760 hectares (1,878 acres) between 2017 (left panel) and 2018 (right panel) along the upper stretches of the Malinowski River in the Madre de Dios region. Red indicates the major deforestation fronts.

As seen in the Land Use Map below (Annex 2), the recent gold mining deforestation along the Upper Malinowski is advancing in the Kotsimba Native Community and within the buffer zone of Bahuaja Sonene National Park.

According to GEOCATMIN, all titled mining concessions in the area are currently “without mining activity.” None are in authorized Exploration or Exploitation phase. Most of the mining activity is outside these concessions and in areas not authorized for mining.

Zoom C: Camanti

Image 4 shows the gold mining deforestation of 335 hectares (828 acres) between 2016 (left panel) and 2018 (right panel) in the Camanti area of the Cusco region. Red indicates the major deforestation fronts. Note the increasing proximity of the mining to Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

As seen in the Land Use Map below (Annex 2), the recent gold mining in the Camanti area is advancing in mining concessions that are “in process” of titling. According to GEOCATMIN, there are no titled concessions in the area that are in Exploration or Exploitation phase.

Annex 1: Reference Map

Annex 1 features a Reference Map of our full study area. The background is white to better indicate the mining deforestation areas. It also serves as a reference map with additional labels.

Annex 2: Land Use Map

Annex 2 features a Land Use Map with detailed data on mining concessions and other important land designations. The mining concession data comes from the web portal GEOCATMIN (Geological Information System and Mining Register), developed by INGEMMET (Geological Mining and Metallurgical Institute of Peru). We downloaded the data on January 2, 2019.

Methodology

We analyzed high-resolution satellite imagery (DigitalGlobe and Planet) for both 2017 and 2018 and digitized all new gold mining deforestation. Given the widespread mining across a large area, we also used automated forest loss alerts based on medium resolution Landsat imagery (PNCB/MINAM) to guide our analysis.

References

Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica (CINCIA) (2018) Tres décadas de deforestación por minería aurífera en la Amazonía suroriental peruana. Resumen de Investigación No. 1.

Caballero Espejo et al. (2018) Deforestation and Forest Degradation Due to Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon: A 34-Year Perspective. Remote Sens. 2018, 10 (12), 1903; https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10121903

Asner GP and Tupayachi R (2016) Environ. Res. Lett. 12 094004.

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Acknowledgements

We thank the following colleagues for helpful comments: Miles Silman (Wake Forest Univ), Sidney Novoa (ACCA), Ronald Catpo (ACCA), Efrain Samochuallpa (ACCA), Daniela Pogliani (ACCA), Alfredo Cóndor (ACCA), and Lorena Durand (ACCA).

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2018) Gold Mining Deforestation at Record High Levels in Southern Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 96.