The Peruvian Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI) recently issued a resolution approving the Update of the Soil and Optimum Land Use Suitability Studies for Areas in the Loreto Region. It is important to emphasize that “Optimum Land Use” (Capacidad de Uso Mayor in Spanish) is not determined by forest cover, but the quantitative interpretation of the soil, climate, and topography.

This new resolution represents an important advance in forest management in Peru because, according to both the previous1 and current2 Forestry Law, if the Optimum Land Use of a particular area is classified as Forest Production or Protection, it is illegal to change the land use to agriculture and cause deforestation. Thus, it is only possible to request land use change if the area has been classified as “Agriculture” (Optimum Land Use Annual Crop, Permanent Crop, or Pasture).3

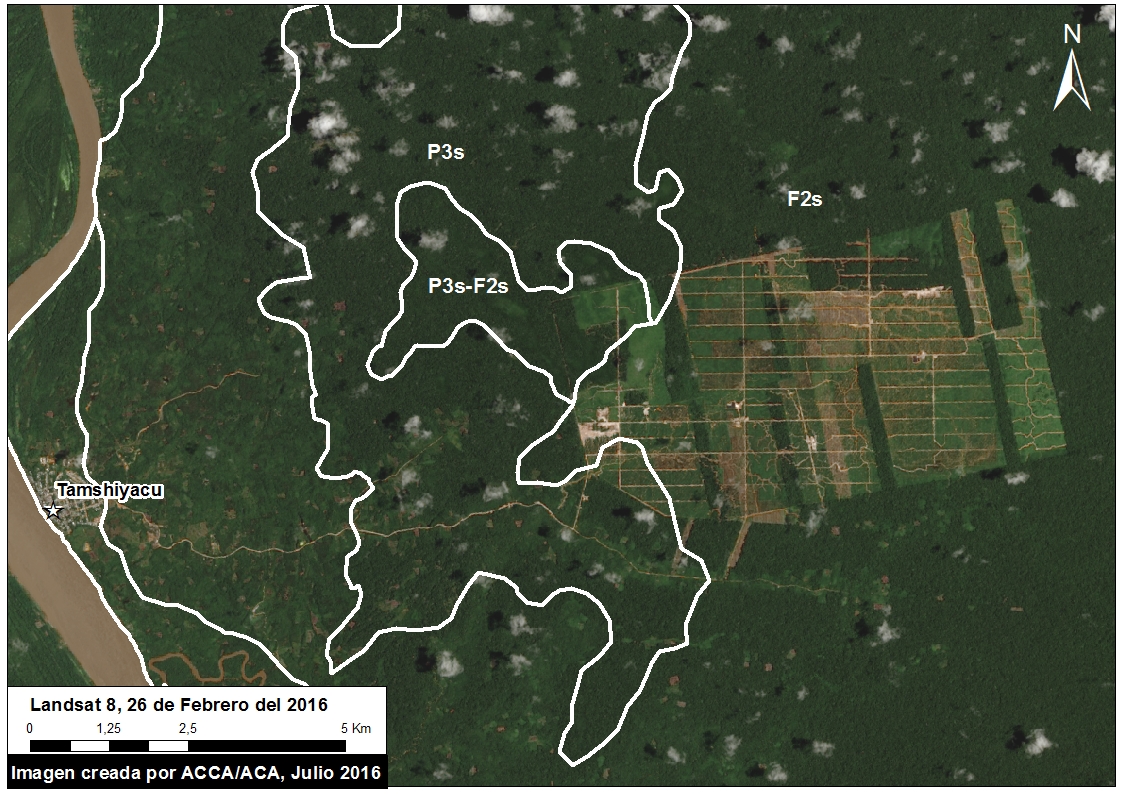

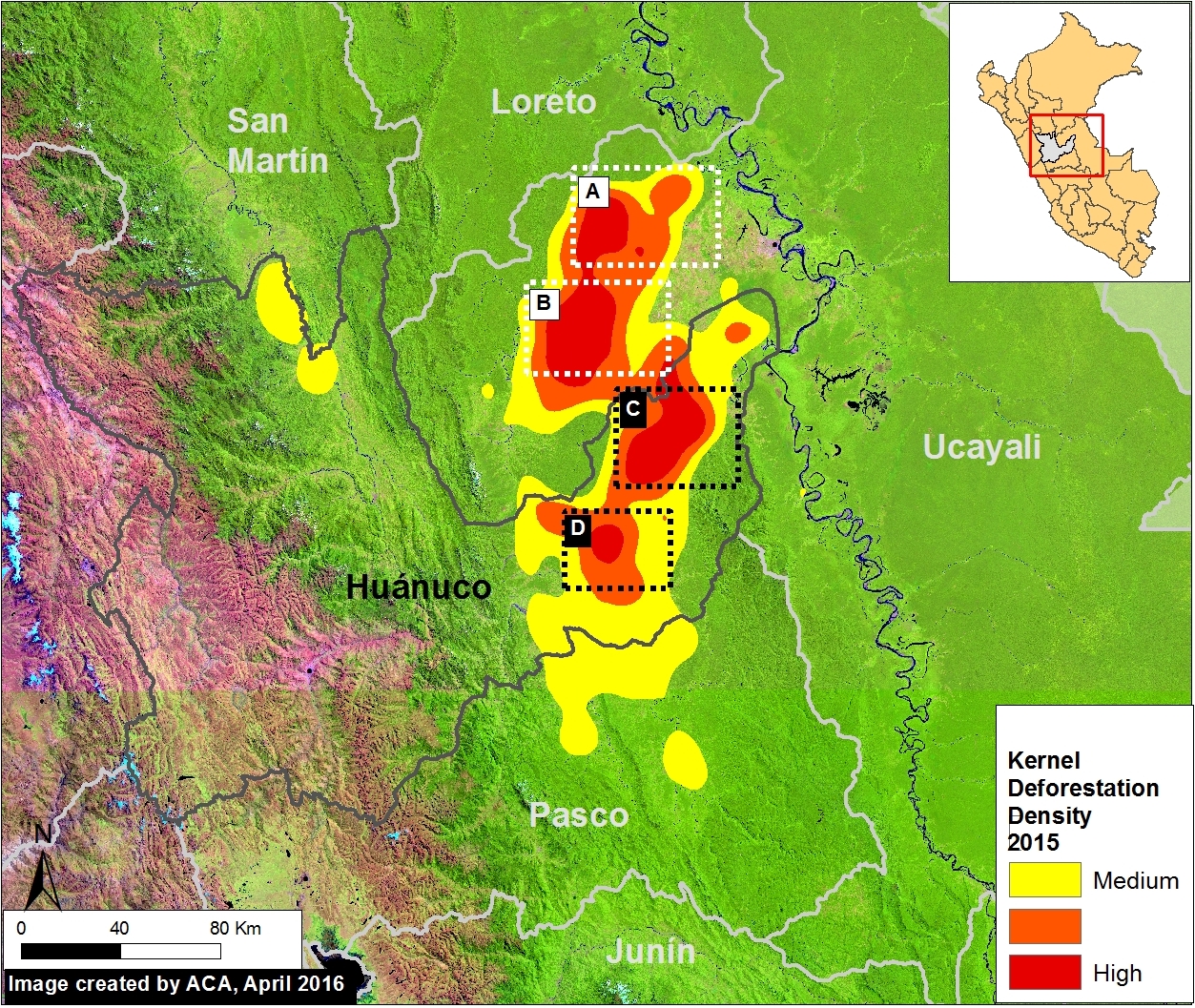

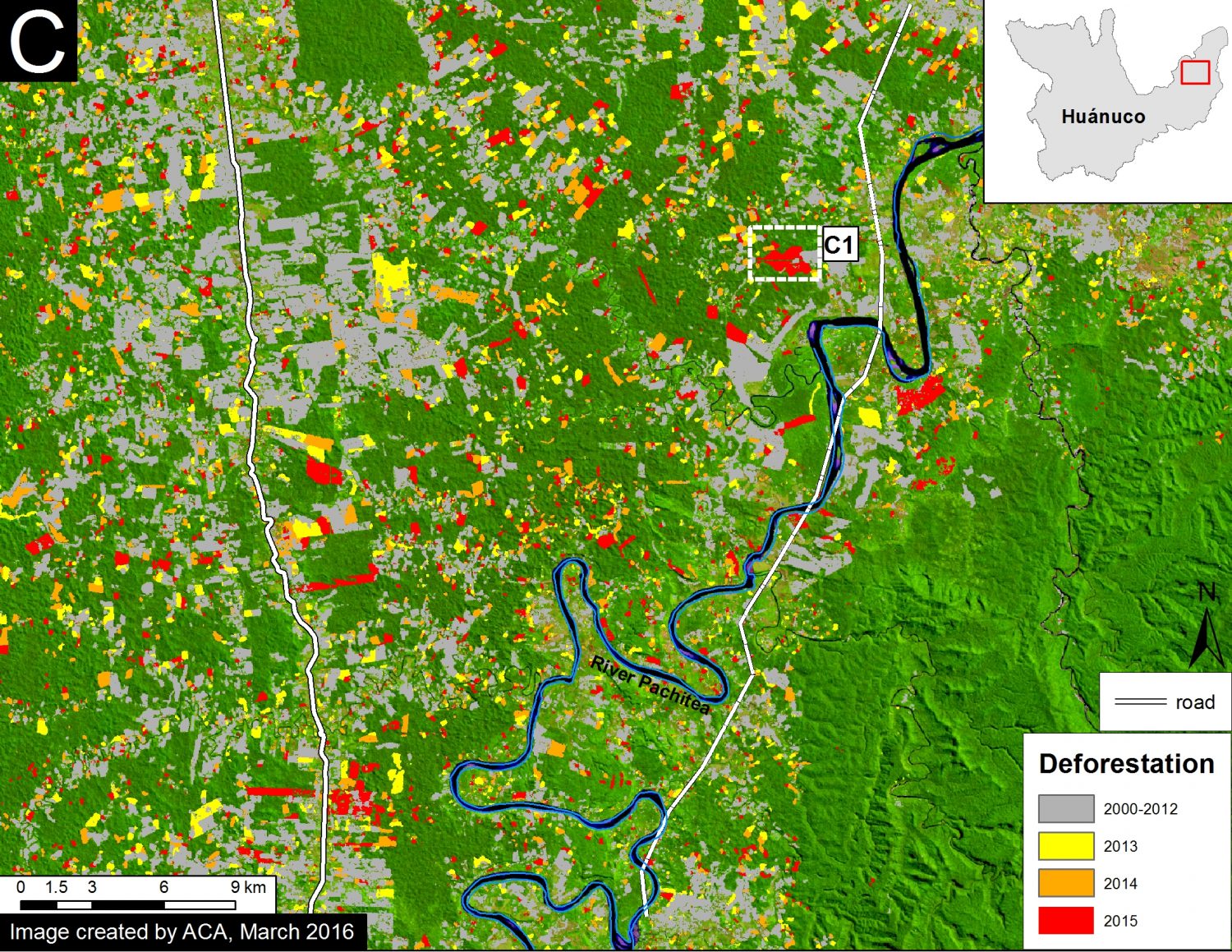

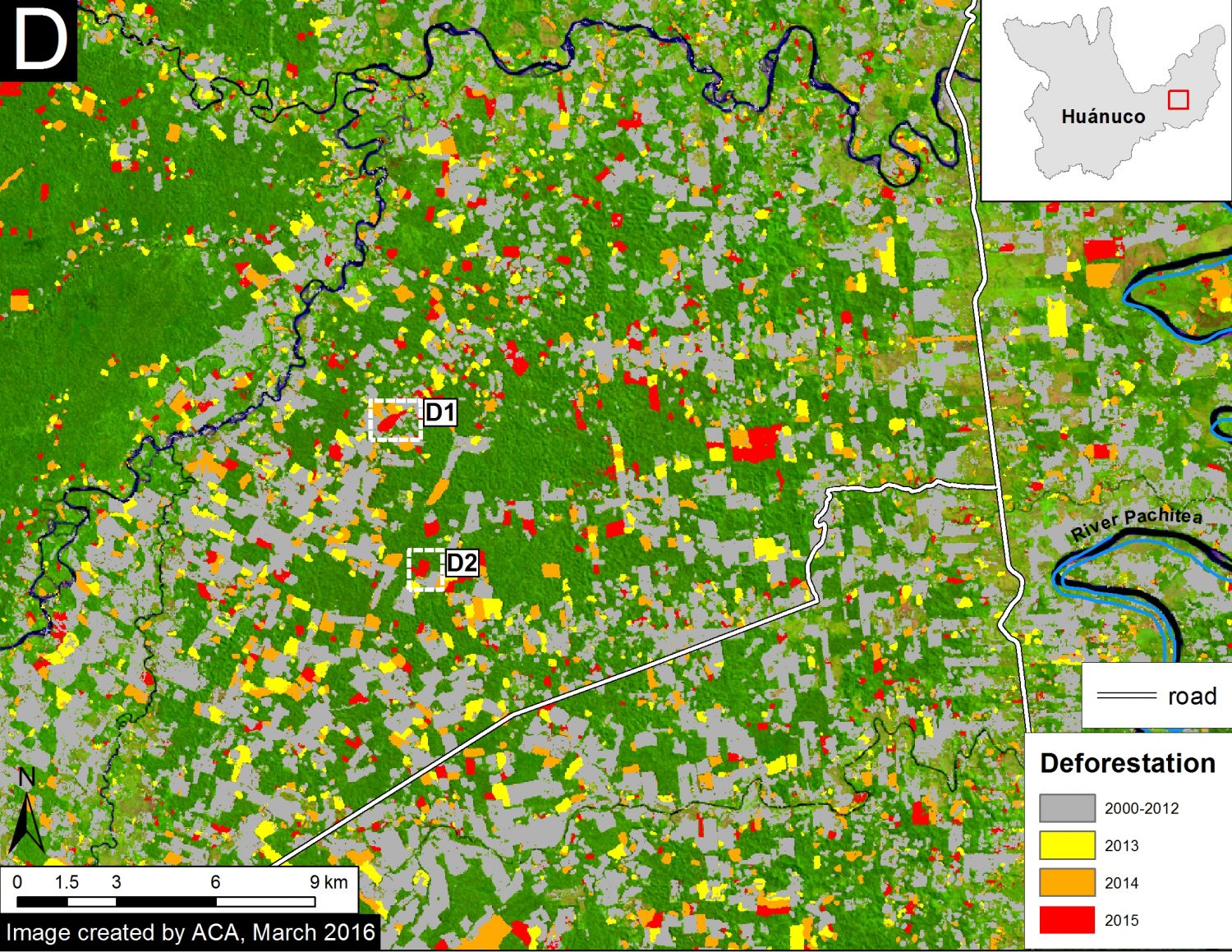

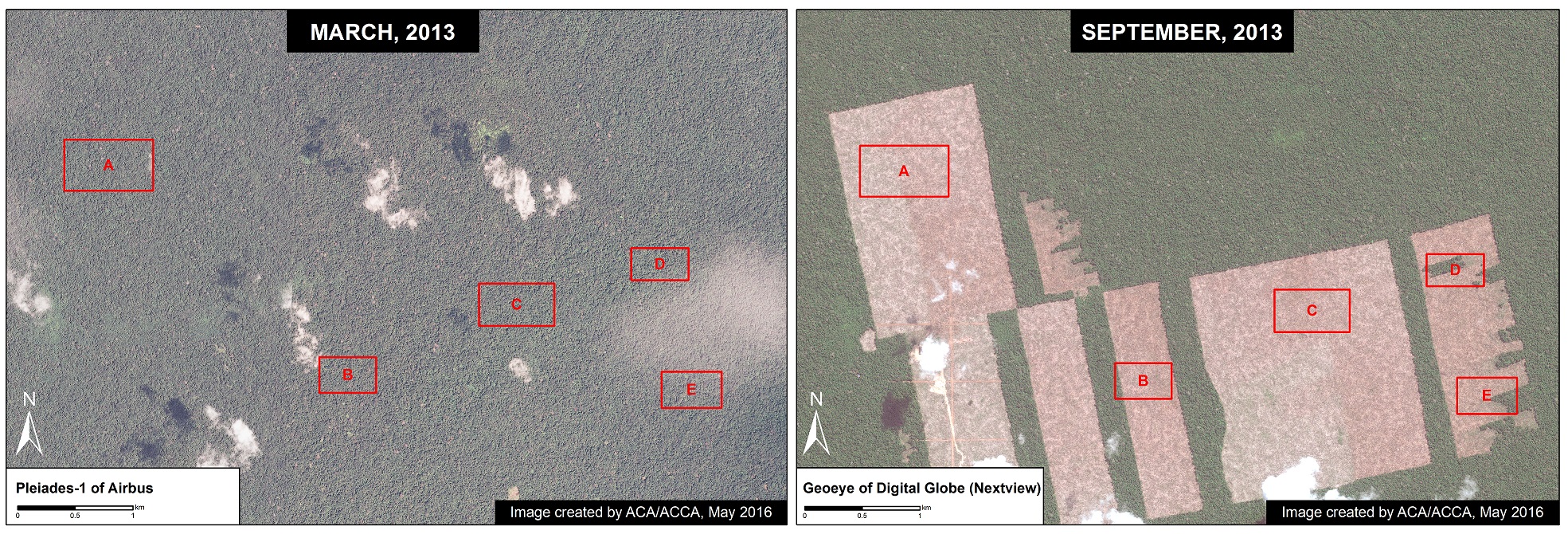

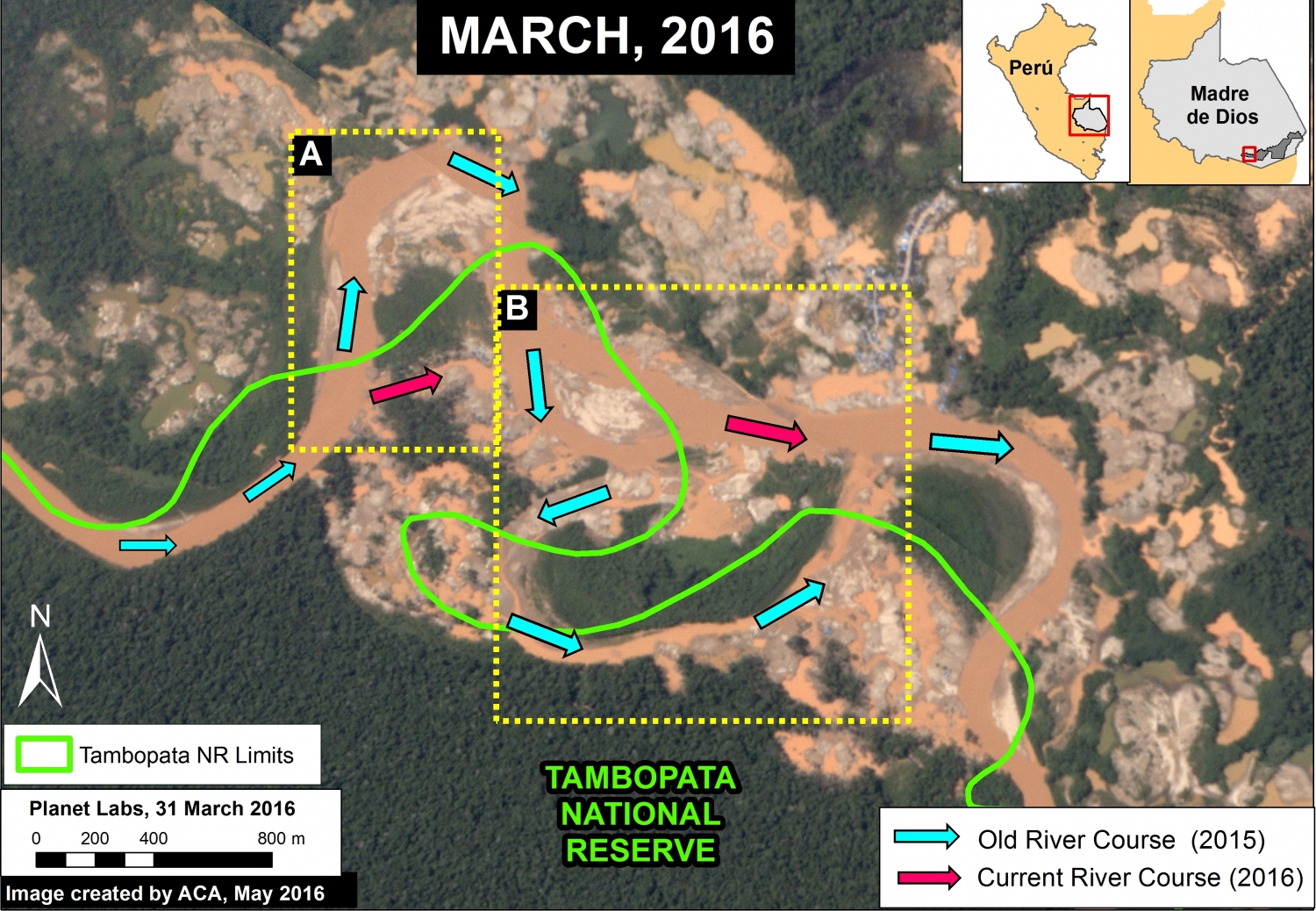

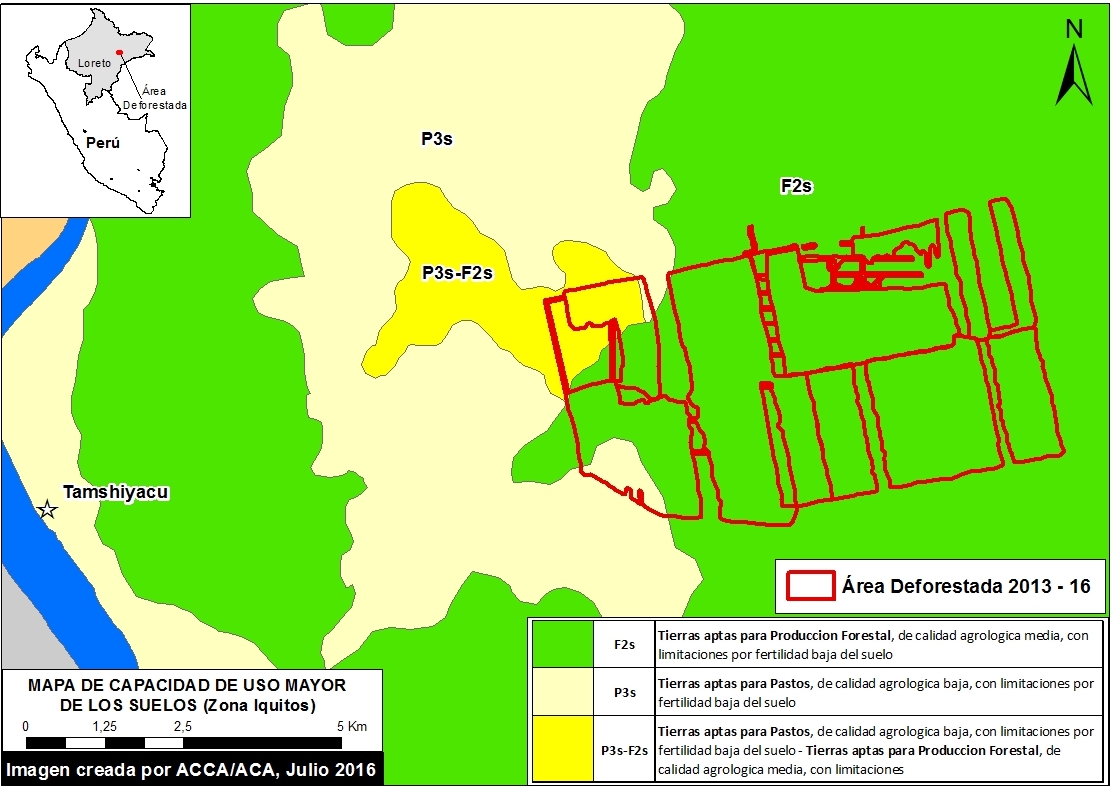

Here, we analyze the spatial data corresponding to the new resolution. In Image 38a, we show that 92.6% (2,200 hectares) of the deforestation4 associated with the United Cacao project occurred on areas with an Optimum Land Use classification of Forest Production5. This classification “groups the lands in which climatic, terrain and soil conditions are not favorable for intensive cultivation, permanent crops, nor pastures, but for the production of timber species.”

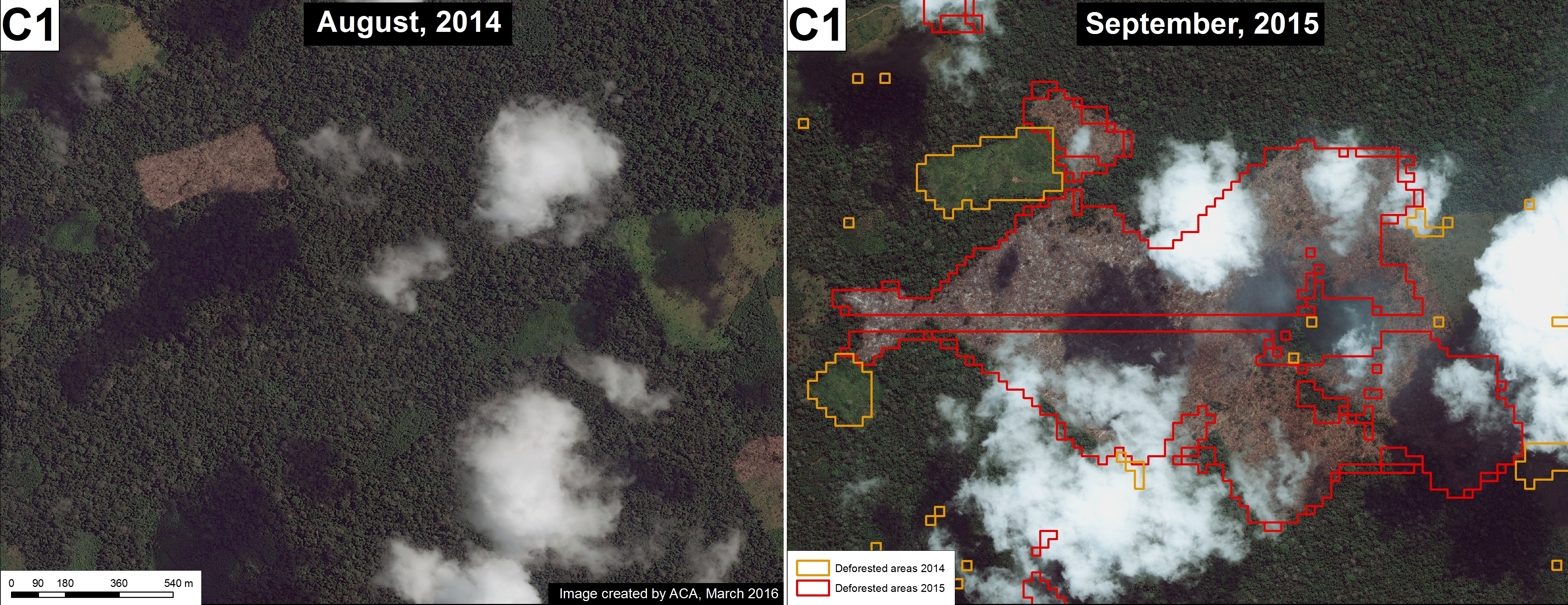

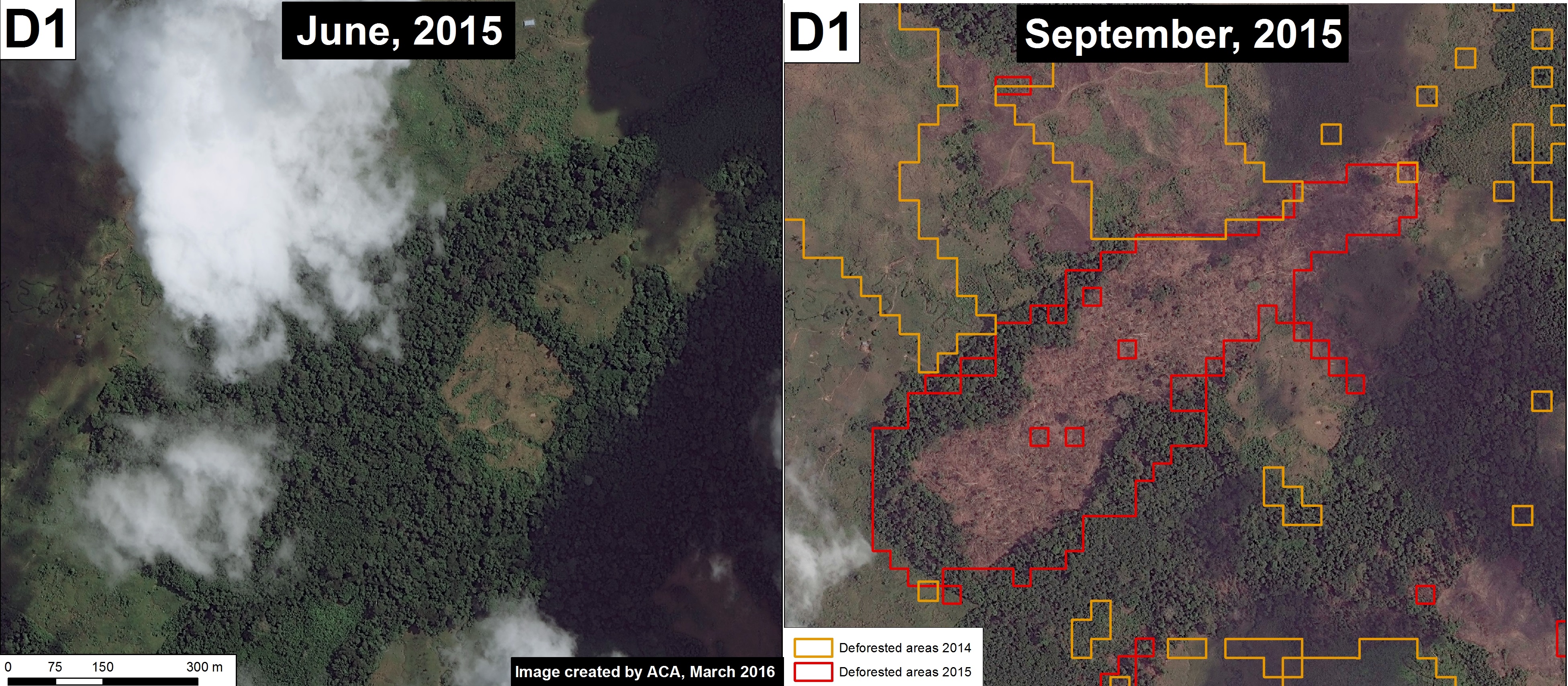

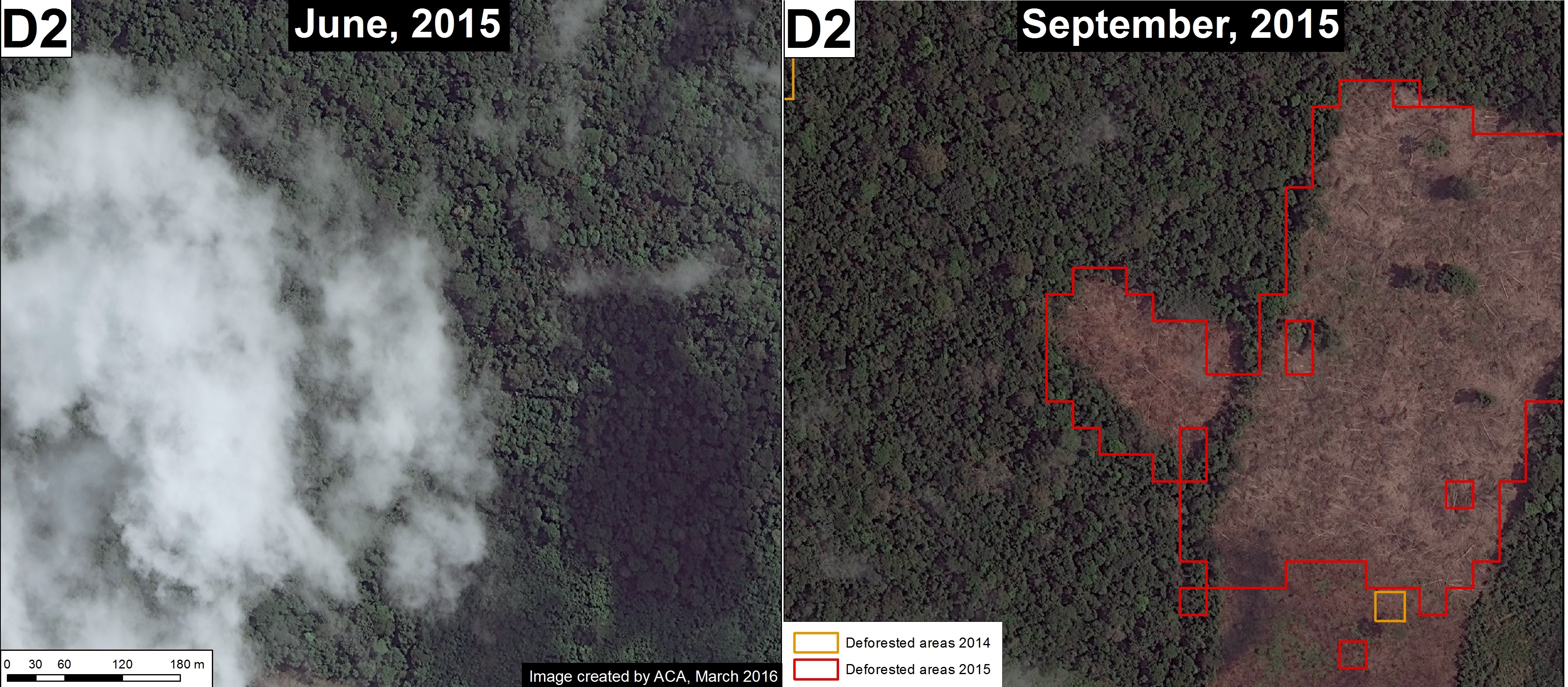

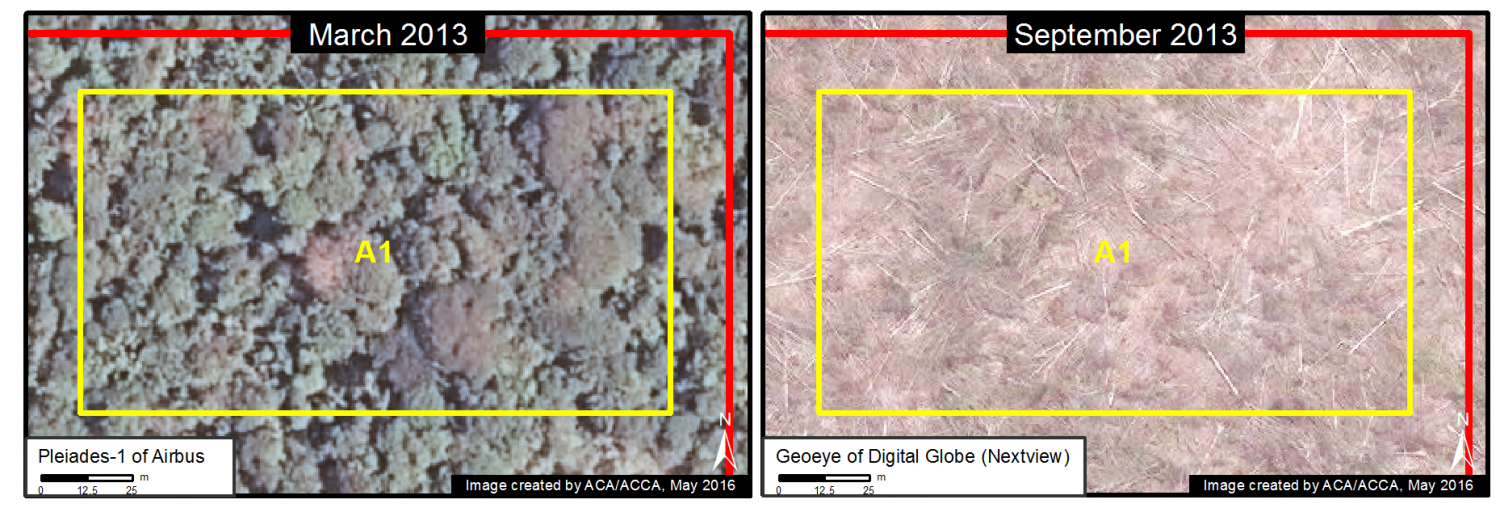

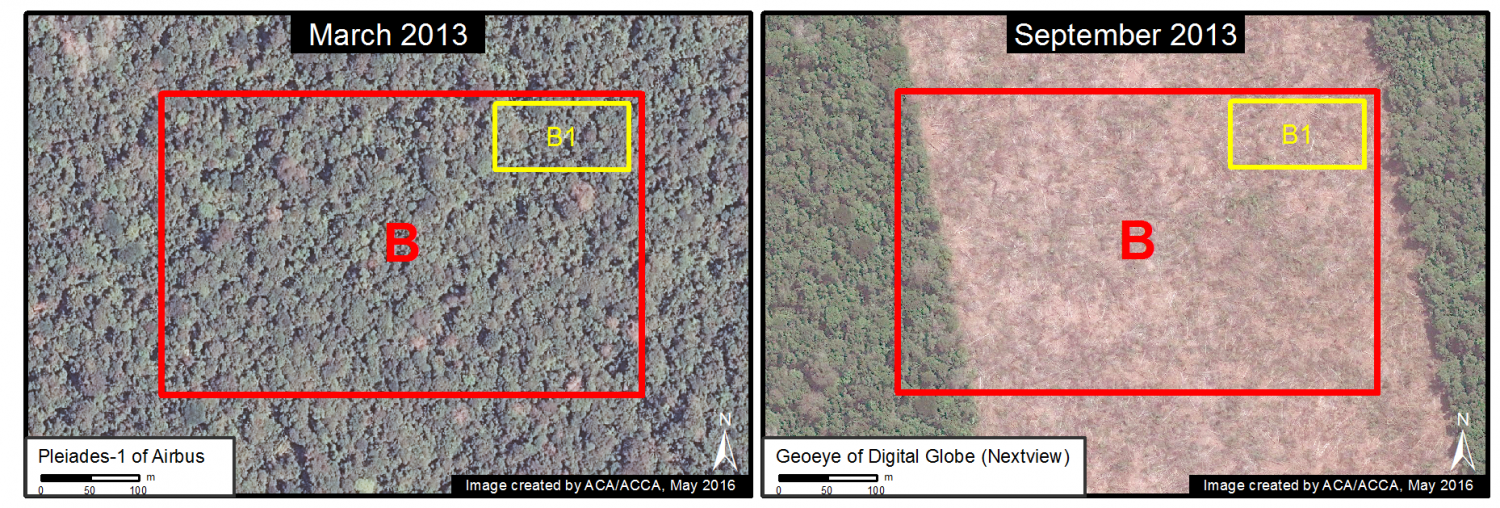

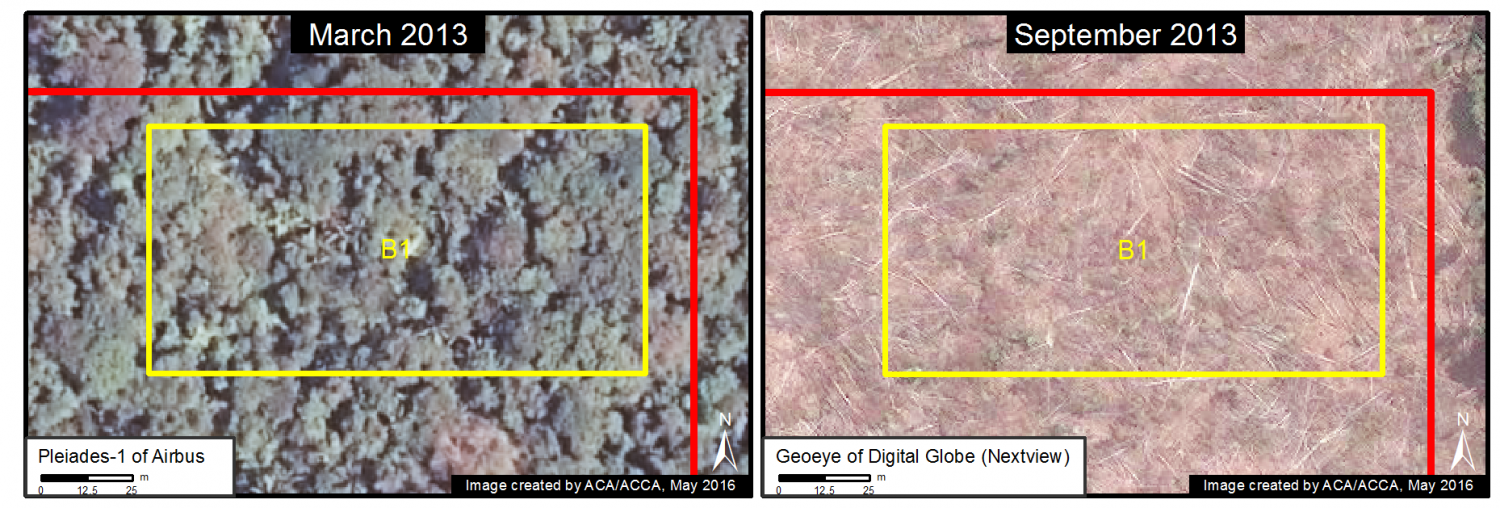

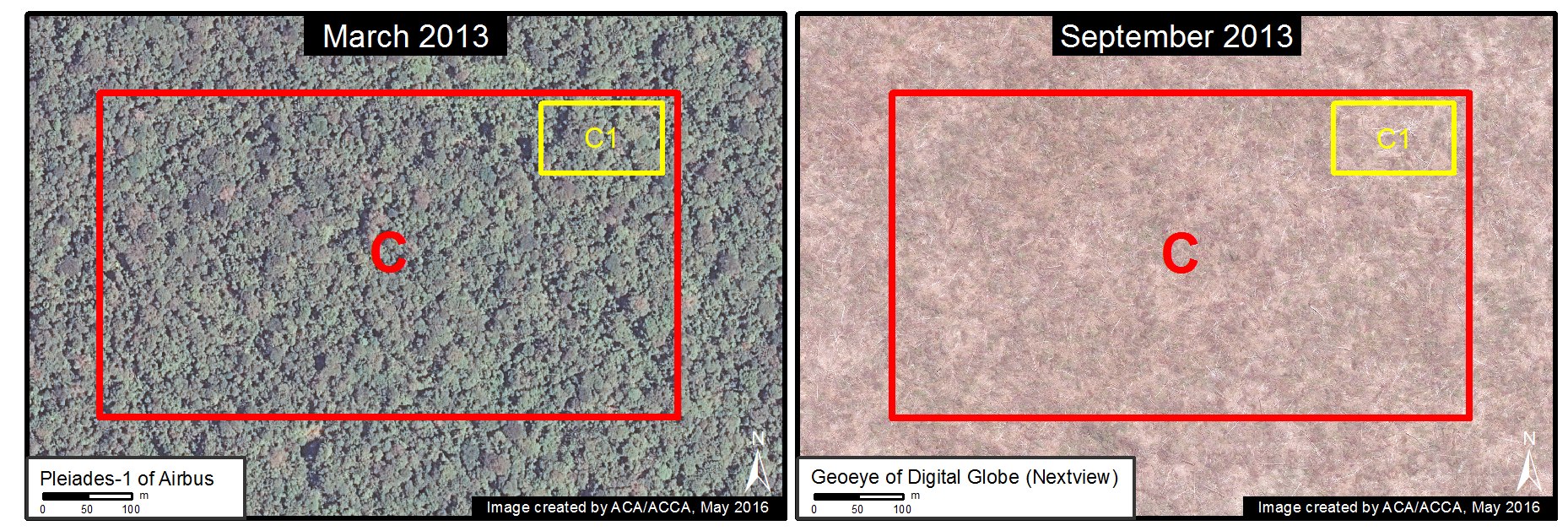

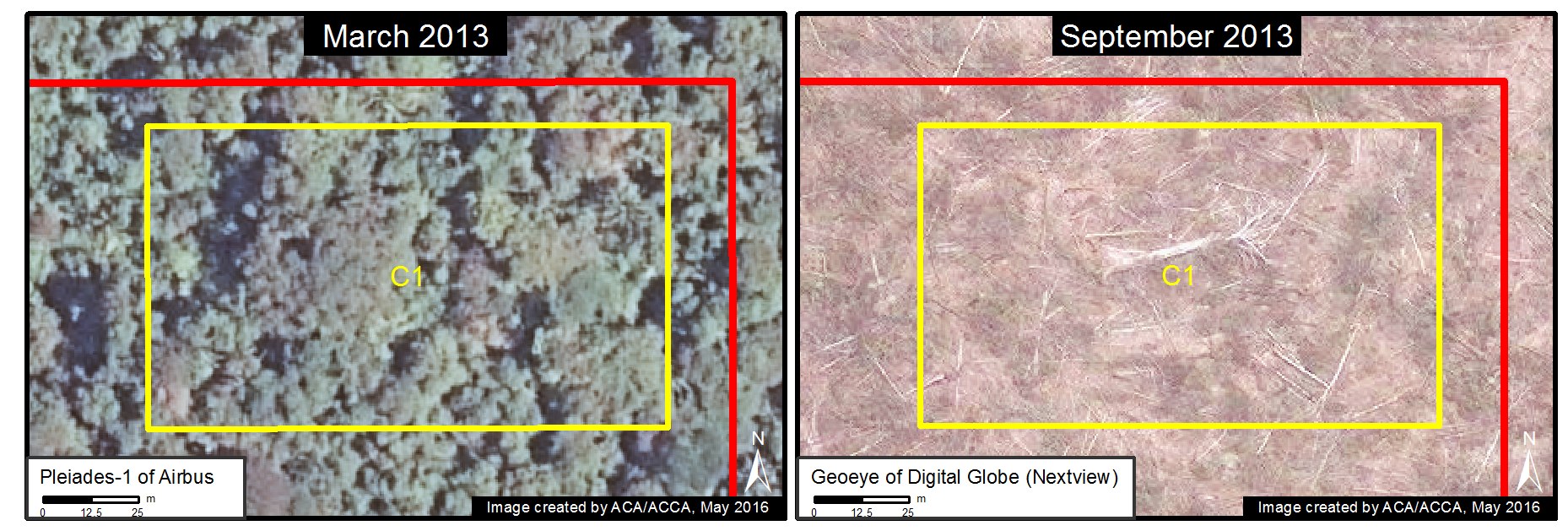

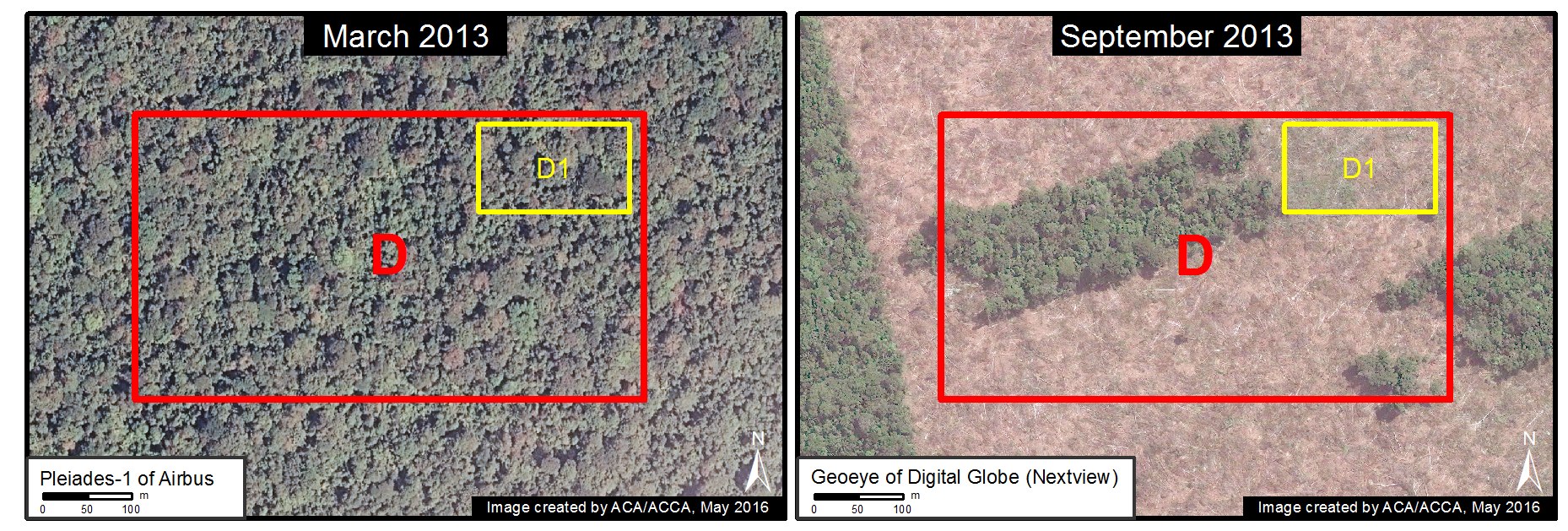

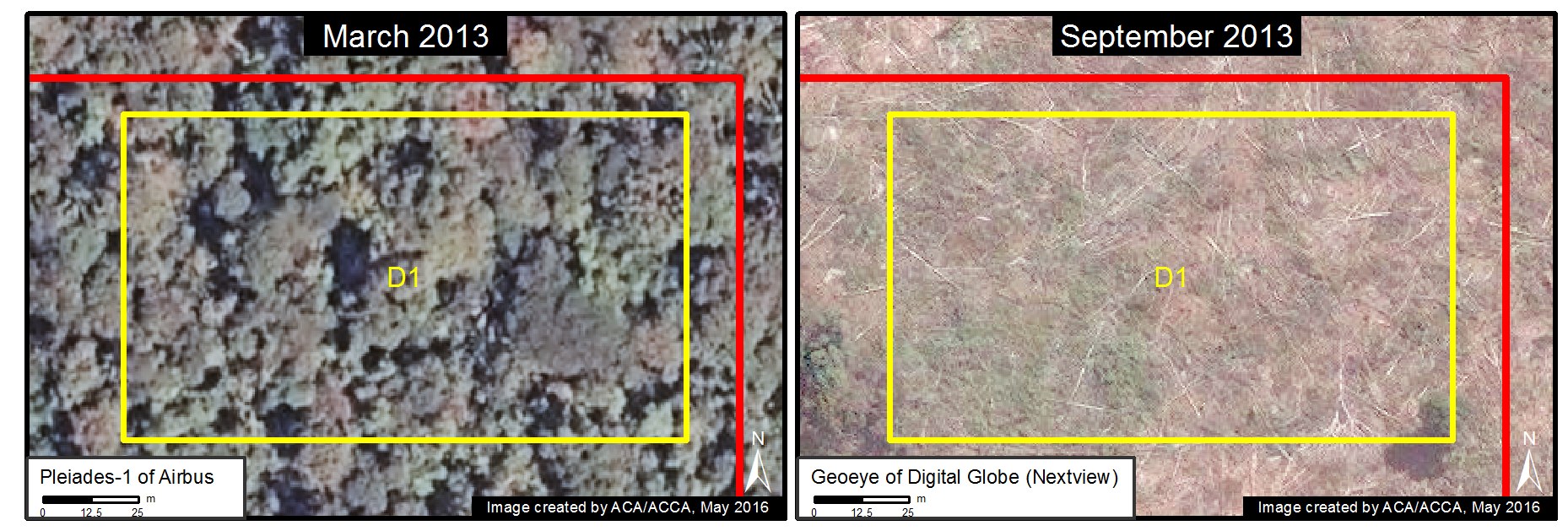

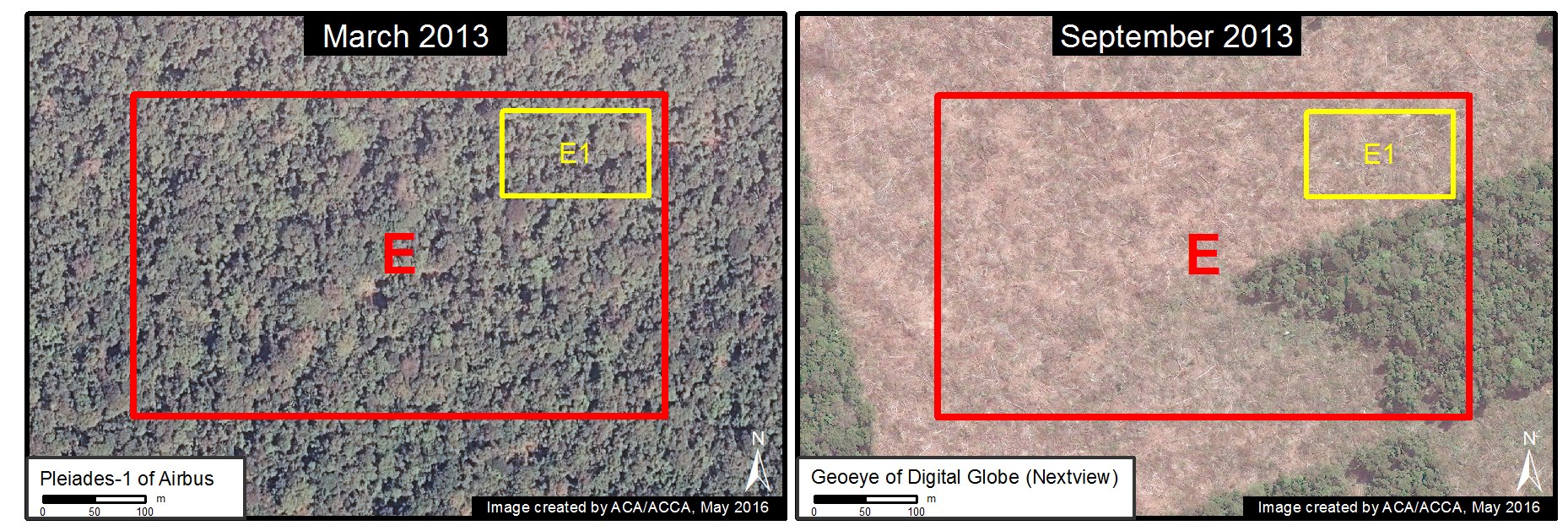

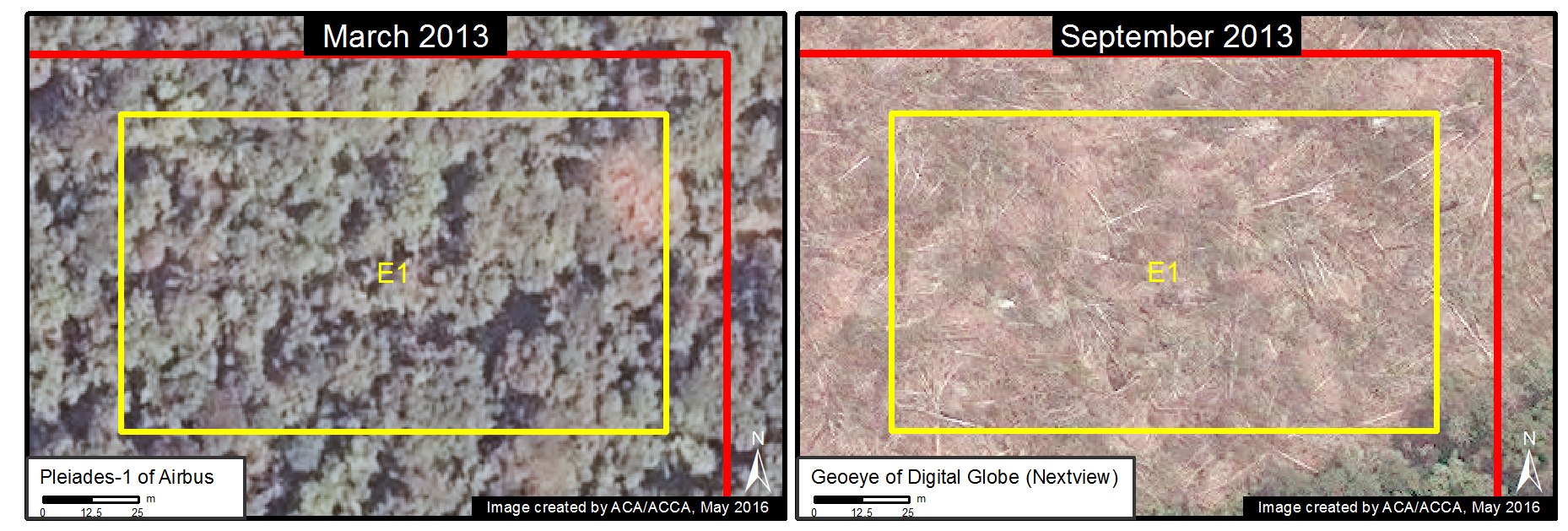

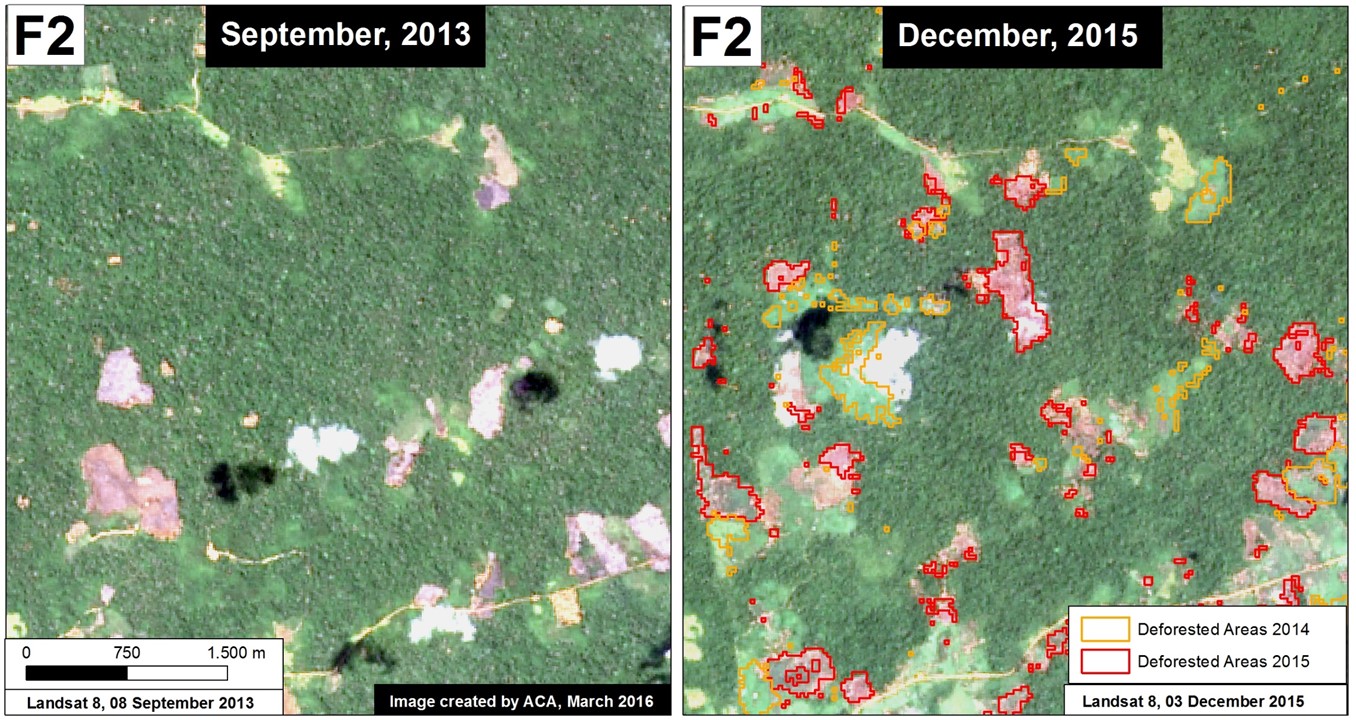

In addition, 3.8% of the deforestation occurred in areas with an Optimum Land Use classification of Pasture/Forestry, while the remaining 3.6% occurred in areas with classification of Pasture. However, it is important to emphasize that even in these areas with an agricultural classification, our analysis of satellite imagery found that they were actually covered with primary forest (see Image 38b).

In conclusion, the vast majority of deforestation caused by United Cacao occurred in areas classified as optimally suited for forest production, where changes in land-use and associated deforestation are not permitted.

Notes

1Ley 27308 Articulo 7. Decreto Supremo 014-2001-AG, Reglamento de la Ley Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre, Art. 36.

2 LEY FORESTAL Y DE FAUNA SILVESTRE (LEY Nº 29763), Artículo 37

3 Decreto Legislativo No. 653, Ley de Promocion de las Inversiones en el Sector Agrario (1991)

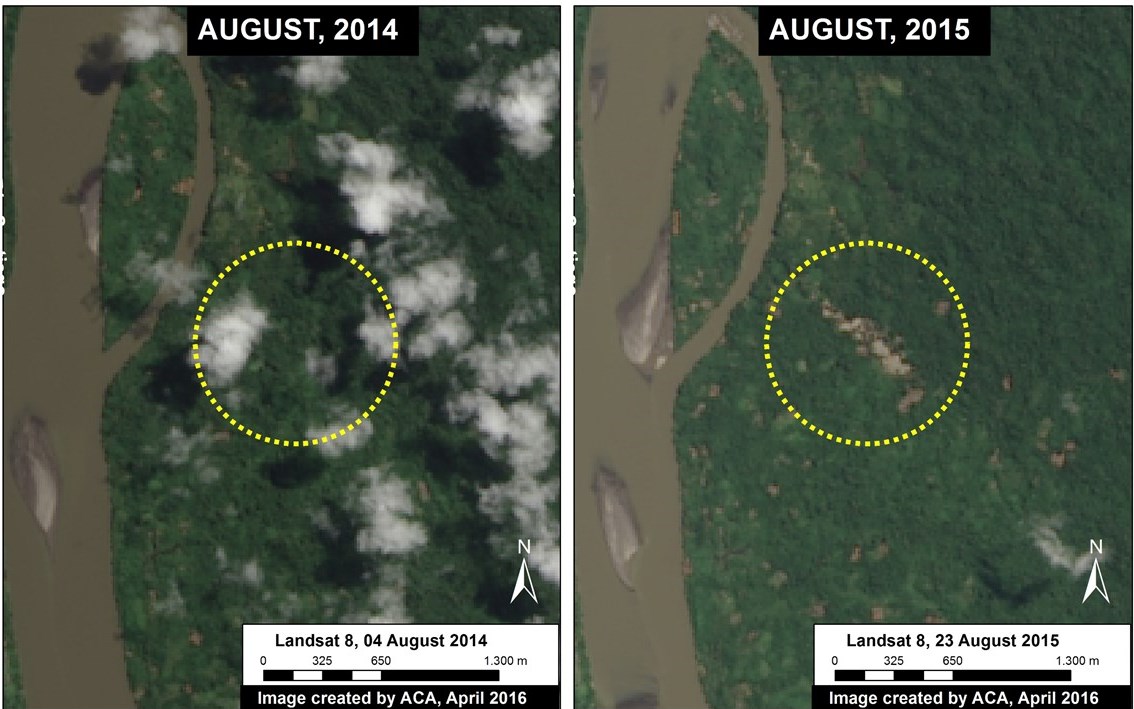

4 See MAAP #35 for more information regarding this deforestation.

5 Specifically, this area is classified as F2s: Tierras Aptas para Producción Forestal (Símbolo F), Clase – Calidad Agrológica Media (Símbolo F2), Subclase – Limitación por Suelo (Símbolo “s”)

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S, Cruz C (2016) United Cacao deforestation in area classified as “Forest Production.” MAAP: 38.